Preface

Images are are one of the best ways to communicate. So it’s understandable that you might feel hoodwinked when you pick up a book filled with words discussing images. Rest assured, you will not be let down. Images are everywhere on the Web—from user-generated content to product advertisement to journalism to security. The creation, design, layout, processing, and delivery of images are no longer the exclusive domain of creative teams. Images on the Web are everyone’s concern.

This book focuses on the essentials of what you need to deliver high performance images on the Internet. This is a very broad topic and covers many domains: color theory, image formats, storage and management, operations delivery, browser and application behavior, responsive web, and many topics in between. With this knowledge we hope that you can glean useful tips, tricks, and practical theory that will help you grow your business as you deliver high performance images.

Who Should Read This Book

We are software developers and wrote this book with developers in mind. Regardless of your role, if you find yourself responsible for any part of the life cycle of images, this book will be useful for you. It is intended to go both broad and deep, to give you background and context while also providing practical advice that will benefit your business.

What This Book Isn’t

There are a great number of subjects that this book will not cover. Specifically, it will avoid topics in the creative process and image editing. It is not about graphic design, image editing tools, or the ways to optimize scratch memory and disk usage. In fact, this book will likely be a disappointment if you are looking for any discussion around RAW formats or video editing. Perhaps that is an opportunity for another book.

Navigating This Book

There is a lot of ground to cover in the area of high performance images. Images are a complex topic, so we have organized the chapters into two major parts: foundations and loading. In the foundation chapters (Part I), we cover image theory and how that applies to the different image formats. Each chapter is designed to stand on its own, so with a little background knowledge you can easily jump from one section to another. In the Loading chapters (Part II), we cover the impacts of these formats on the browser, the device, and the network.

Why We Wrote This Book

Thinking about images always reminds me of a fishing trip where I met the most cantankerous marlin in the freshwater lakes of Northern Canada. The fish was so big that it took nearly 45 minutes of wrestling to bring it aboard my canoe. At times, I wondered if I was going to be dragged to the depths of the lake. It was a whopping 1.5 m long and weighed 35 kg!

Pictures! Or it never happened.

If I were you, I’d be skeptical of my claims. To be honest, even I don’t believe what I just wrote. I’ve never been fishing in my life! Not only that, but marlin live in the warmer Pacific Ocean, not the spring-fed lakes from the Atlantic Ocean. You are probably more likely to find a 35 kg beaver than a fish that size.

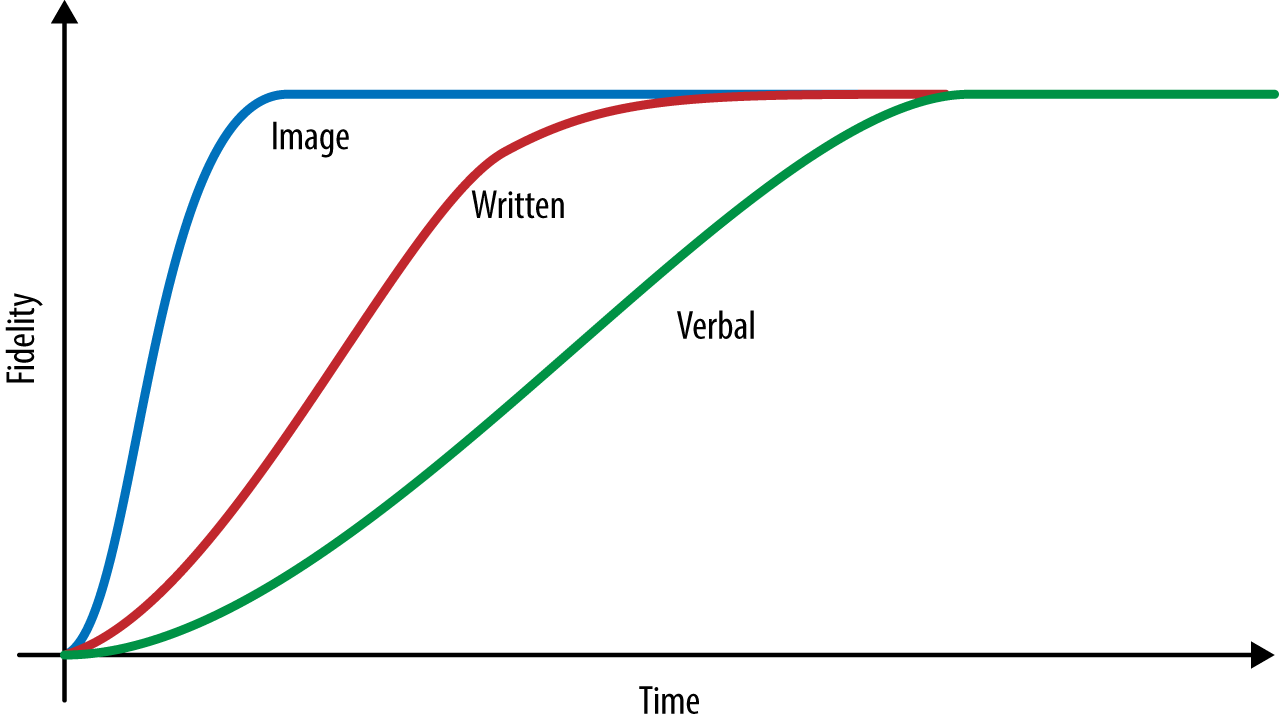

Images are at the core of storytelling, journalism, and advertising. We are good at re-telling stories, but they can easily change from person to person. Remember the childhood game of “Telephone,” where one kid whispers a phrase to the next person around a circle? The phrase “high performance images” would undoubtedly be transformed to “baby fart fart” in a circle of eight-year-old boys. But if we include a photograph, then the story gains fidelity and is less likely to change. Images add credibility to our stories.

The challenge is always in creating and communicating imagery. The fishing story created an image in your mind using 369 characters. Gzipped, that’s 292 bytes for a mental image like the example in Figure P-1. But that image was just words and thus not reliable like the photo in Figure P-2.

Figure P-1. 292 bytes to create an image in your mind’s eye

Figure P-2. In contrast, the photograph is 2.4 MB, which reveals my fraud (not me, not Canada, somewhere warm)

Words can conjure images fast but are very prone to corruption and low fidelity. Unless you know something about marlins, the geography of Northern Canada, or my angling expertise, you can’t really grasp how “fishy” my story sounds. To get that detail you have to ask questions, questions that take time to send. To develop a high quality image in your mind, you need more time (see Figure P-3).

If only there were a more efficient way to communicate images—a way to communicate with high performance, if you will.

Figure P-3. How much time it takes to communicate image fidelity: graphical, written, and verbal1

Historically, creating images and graphics was hard. Cave paintings require specialized mixtures of substances and are prone to fading and washing away. You certainly wouldn’t want to waste your efforts creating a cave painting of a cat playing a piano! Over the last century, photography has certainly made images cheaper and less laborious to produce. Yet, with each advance in image creation, we have increased the challenge of transmission. Just think of the complexity of adding images to a book prior to modern software. Printing an image involved creating plates that were inked separately for each color used and then pressed one at a time on the same page—very inefficient!

With ubiquitous smartphones equipped with high-quality cameras, we can take high-resolution images in mere milliseconds. And yet, despite this ease, it is still challenging to send and receive photos. The problem is that—despite the facts that our screen displays are high resolution and have high pixel density ratios; our websites and applications have richer content; our cameras are capable of taking high-quality photographs; and our image libraries have grown—it feels as though our ISPs and mobile networks cannot keep up with the insatiable user demands for data.

This transmission challenge affects not only photos, but also the interfaces for our applications and websites. These too are increasingly using graphics and images to aid users in completing their work more efficiently and more effectively. Yet, if we cannot transmit these graphical interfaces efficiently or render them on the screens with high performance, then we are no better off than if we were trying to do a Gopher search on an old VIC-20. While any reference to dark age computing warms the depths of my heart, I want to believe our technology has enabled us to be more effective in our jobs and advanced our ability to transmit images.

This is where we start: no more fish tales. We begin with the question of how we communicate and present images and graphics to a user with high performance. This book is about high performance images, but it is also a story about rasters and vectors, icons, graphics, and bitmaps. It is the story of an evolving communication medium. It is also the story of journalism, free speech, and commerce. Without high performance images, how would we share cultural memes like the blue and white (or was that gold and black?) dress or share the unsettling reality of the Arab Spring? We need high performance images.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Pat Meenan and Eric Lawrence for providing detailed feedback throughout the writing of this book. And special thanks to Yaara Weiss for providing the foxy fox illustrations in Chapter 11.

Conventions Used in This Book

The following typographical conventions are used in this book:

- Italic

-

Indicates new terms, URLs, email addresses, filenames, and file extensions.

Constant width-

Used for program listings, as well as within paragraphs to refer to program elements such as variable or function names, databases, data types, environment variables, statements, and keywords.

Constant width bold-

Shows commands or other text that should be typed literally by the user.

Constant width italic-

Shows text that should be replaced with user-supplied values or by values determined by context.

Tip

This element signifies a tip or suggestion.

Note

This element signifies a general note.

Warning

This element indicates a warning or caution.

Using Code Examples

This book is here to help you get your job done. In general, if example code is offered with this book, you may use it in your programs and documentation. You do not need to contact us for permission unless you’re reproducing a significant portion of the code. For example, writing a program that uses several chunks of code from this book does not require permission. Selling or distributing a CD-ROM of examples from O’Reilly books does require permission. Answering a question by citing this book and quoting example code does not require permission. Incorporating a significant amount of example code from this book into your product’s documentation does require permission.

We appreciate, but do not require, attribution. An attribution usually includes the title, author, publisher, and ISBN. For example: “High Performance Images by Colin Bendell, Tim Kadlec, Yoav Weiss, Guy Podjarny, Nick Doyle, and Mike McCall (O’Reilly). Copyright 2016 Akamai Technologies, 978-1-4919-3826-3.”

If you feel your use of code examples falls outside fair use or the permission given above, feel free to contact us at permissions@oreilly.com.

Safari® Books Online

Note

Safari Books Online is an on-demand digital library that delivers expert content in both book and video form from the world’s leading authors in technology and business.

Technology professionals, software developers, web designers, and business and creative professionals use Safari Books Online as their primary resource for research, problem solving, learning, and certification training.

Safari Books Online offers a range of plans and pricing for enterprise, government, education, and individuals.

Members have access to thousands of books, training videos, and prepublication manuscripts in one fully searchable database from publishers like O’Reilly Media, Prentice Hall Professional, Addison-Wesley Professional, Microsoft Press, Sams, Que, Peachpit Press, Focal Press, Cisco Press, John Wiley & Sons, Syngress, Morgan Kaufmann, IBM Redbooks, Packt, Adobe Press, FT Press, Apress, Manning, New Riders, McGraw-Hill, Jones & Bartlett, Course Technology, and hundreds more. For more information about Safari Books Online, please visit us online.

How to Contact Us

Please address comments and questions concerning this book to the publisher:

- O’Reilly Media, Inc.

- 1005 Gravenstein Highway North

- Sebastopol, CA 95472

- 800-998-9938 (in the United States or Canada)

- 707-829-0515 (international or local)

- 707-829-0104 (fax)

We have a web page for this book, where we list errata, examples, and any additional information. You can access this page at http://shop.oreilly.com/product/0636920039730.do.

To comment or ask technical questions about this book, send email to bookquestions@oreilly.com.

For more information about our books, courses, conferences, and news, see our website at http://www.oreilly.com.

Find us on Facebook: http://facebook.com/oreilly

Follow us on Twitter: http://twitter.com/oreillymedia

Watch us on YouTube: http://www.youtube.com/oreillymedia

1 Bailey, R.W. and Bailey, L.M. (1999), Reading speeds using RSVP, User Interface Update (400 words per minute) (http://www.humanfactors1.com/downloads/feb99.asp); and Omoigui, N., He, L., Gupta A., Grudin, J. and Sanocki, E. (1999), Time-compression: Systems concerns, usage, and benefits, CHI 99 Conference Proceedings, 136-143 (210 words per minute).

Get High Performance Images now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.