Preface

Preface to the Third Edition

Java 8 is the new kid on the block. Java 7 was a significant but incremental improvement over its predecessors. So much has changed since the previous edition of this book! What was “new in Java 5” has become ubiquitous in Java: annotations, generic types, concurrency utilities, and more. APIs have come and gone across the entire tableau of Java: JavaME is pretty much dead now that BlackBerry has abandoned it; JSF is (slowly) replacing JSP in parts of Enterprise Java; and Spring continues to expand its reach. Many people seem to think that “desktop Java” is dead or even that “Java is dying,” but it is definitely not rolling over yet; Swing, JavaFX, Java Enterprise, and (despite a major lawsuit by Oracle) Android are keeping the Java language very much alive. Additionally, a renewed interest in other “JVM languages” such as Groovy, JRuby, Jython, Scala, and Clojure is keeping the platform in the forefront of the development world.

Indeed, the main challenge in preparing this third edition has been narrowing down the popular APIs, keeping my own excitement and biases in check, to make a book that will fit into the size constraints established by the O’Reilly Cookbook series and my own previous editions. The book has to remain around 900 pages in length, and it certainly would not were I to try to fit in “all that glistens.”

I’ve also removed certain APIs that were in the previous editions. Most notable is the chapter on serial and parallel ports (pared down to one recipe in Chapter 10); computers generally don’t ship with these anymore, and hardly anybody is using them: the main attention has moved to USB, and there doesn’t seem to be a standard API for Java yet (nor, frankly, much real interest among developers).

Preface to Previous Editions

If you know a little Java, great. If you know more Java, even better! This book is ideal for anyone who knows some Java and wants to learn more. If you don’t know any Java yet, you should start with one of the more introductory books, such as Head First Java (O’Reilly) or Learning Java (O’Reilly) if you’re new to this family of languages, or Java in a Nutshell (O’Reilly) if you’re an experienced C programmer.

I started programming in C in 1980 while working at the University of Toronto, and C served me quite well through the 1980s and into the 1990s. In 1995, as the nascent language Oak was being renamed Java, I had the good fortune of being told about it by my colleague J. Greg Davidson. I sent an email to the address Greg provided, and got this mail back from James Gosling, Java’s inventor, in March 1995:

| Hi. A friend told me about WebRunner(?), your extensible network | browser. It and Oak(?) its extension language, sounded neat. Can | you please tell me if it's available for play yet, and/or if any | papers on it are available for FTP? Check out http://java.sun.com (oak got renamed to java and webrunner got renamed to hotjava to keep the lawyers happy)

So Oak became Java[1] before I could get started with it. I downloaded HotJava and began to play with it. At first I wasn’t sure about this newfangled language, which looked like a mangled C/C++. I wrote test and demo programs, sticking them a few at a time into a directory that I called javasrc to keep it separate from my C source (because often the programs would have the same name). And as I learned more about Java, I began to see its advantages for many kinds of work, such as the automatic memory reclaim (“garbage collection”) and the elimination of pointer calculations. The javasrc directory kept growing. I wrote a Java course for Learning Tree,[2] and the directory grew faster, reaching the point where it needed subdirectories. Even then, it became increasingly difficult to find things, and it soon became evident that some kind of documentation was needed.

In a sense, this book is the result of a high-speed collision between my javasrc directory and a documentation framework established for another newcomer language. In O’Reilly’s Perl Cookbook, Tom Christiansen and Nathan Torkington worked out a very successful design, presenting the material in small, focused articles called “recipes,” for the then-new Perl language. The original model for such a book is, of course, the familiar kitchen cookbook. Using the term “cookbook” to refer to an enumeration of how-to recipes relating to computers has a long history. On the software side, Donald Knuth applied the “cookbook” analogy to his book The Art of Computer Programming (Addison-Wesley), first published in 1968. On the hardware side, Don Lancaster wrote The TTL Cookbook (Sams). (Transistor-transistor logic, or TTL, was the small-scale building block of electronic circuits at the time.) Tom and Nathan worked out a successful variation on this, and I recommend their book for anyone who wishes to, as they put it, “learn more Perl.” Indeed, the work you are now reading strives to be the book for the person who wishes to “learn more Java.”

The code in each recipe is intended to be largely self-contained; feel free to borrow bits and pieces of any of it for use in your own projects. The code is distributed with a Berkeley-style copyright, just to discourage wholesale reproduction.

Who This Book Is For

I’m going to assume that you know the basics of Java. I won’t tell

you how to println a string and a number at the same time, or how

to write a class that extends JFrame and prints your name in the

window. I’ll presume you’ve taken a Java course or studied an

introductory book such as Head First Java, Learning Java, or Java in a Nutshell (O’Reilly). However, Chapter 1 covers some techniques that you

might not know very well and that are necessary to understand some

of the later material. Feel free to skip around! Both the printed

version of the book and the electronic copy are heavily cross-referenced.

What’s in This Book?

Unlike my Perl colleagues Tom and Nathan, I don’t have to spend as much time on the oddities and idioms of the language; Java is refreshingly free of strange quirks.[3] But that doesn’t mean it’s trivial to learn well! If it were, there’d be no need for this book. My main approach, then, is to concentrate on the Java APIs. I’ll teach you by example what the important APIs are and what they are good for.

Like Perl, Java is a language that grows on you and with you. And, I confess, I use Java most of the time nowadays. Things I once did in C—except for device drivers and legacy systems—I now do in Java.

Java is suited to a different range of tasks than Perl, however. Perl (and other scripting languages, such as awk and Python) is particularly suited to the “one-liner” utility task. As Tom and Nathan show, Perl excels at things like printing the 42nd line from a file. Although Java can certainly do these things, it seems more suited to “development in the large,” or enterprise applications development, because it is a compiled, object-oriented language. Indeed, much of the API material added in Java 2 was aimed at this type of development. However, I will necessarily illustrate many techniques with shorter examples and even code fragments. Be assured that every fragment of code you see here (except for some one- or two-liners) has been compiled and run.

Some of the longer examples in this book are tools that I originally wrote to automate some mundane task or another. For example, a tool called MkIndex (in the javasrc repository) reads the top-level directory of the place where I keep all my Java example source code and builds a browser-friendly index.html file for that directory. For another example, the body of the first edition was partly composed in XML (see Chapter 20);

I used XML to type in and mark up the original text of some of the chapters of this book, and text was then converted to the publishing software format by the XmlForm program. This program also handled—by use of another program, GetMark—full and partial code insertions from the javasrc directory into the book manuscript. XmlForm is discussed in Chapter 20.

Organization of This Book

Let’s go over the organization of this book. I start off Chapter 1, Getting Started: Compiling, Running, and Debugging by describing some methods of compiling your program on different platforms, running them in different environments (browser, command line, windowed desktop), and debugging.

Chapter 2, Interacting with the Environment moves from compiling and running your program to getting it to adapt to the surrounding countryside—the other programs that live in your computer.

The next few chapters deal with basic APIs. Chapter 3, Strings and Things concentrates on one of the most basic but powerful data types in Java, showing you how to assemble, dissect, compare, and rearrange what you might otherwise think of as ordinary text.

Chapter 4, Pattern Matching with Regular Expressions teaches you how to use the powerful regular expressions technology from Unix in many string-matching and pattern-matching problem domains. “Regex” processing has been standard in Java for years, but if you don’t know how to use it, you may be “reinventing the flat tire.”

Chapter 5, Numbers deals both with built-in numeric types such as int and double, as well as the corresponding API classes (Integer, Double, etc.) and the conversion and testing facilities they offer. There is also brief mention of the “big number” classes. Because Java programmers often need to deal in dates and times, both locally and internationally, Chapter 6, Dates and Times—New API covers this important topic.

The next two chapters cover data processing. As in most languages, arrays in Java are linear, indexed collections of similar-kind objects, as discussed in Chapter 7, Structuring Data with Java. This chapter goes on to deal with the many “Collections” classes: powerful ways of storing quantities of objects in the java.util package, including use of “Java Generics.”

Despite some syntactic resemblance to procedural languages such as C, Java is at heart an object-oriented programming (OOP) language. Chapter 8, Object-Oriented Techniques discusses some of the key notions of OOP as it applies to Java, including the commonly overridden methods of java.lang.Object and the important issue of design patterns.

Java is not, and never will be, a pure “functional programming” (FP) language. However, it is possible to use some aspects of FP, increasingly so with Java 8 and its support of “lambda expressions” (a.k.a. “closures”). This is discussed in Chapter 9, Functional Programming Techniques: Functional Interfaces, Streams, Parallel Collections.

The next few chapters deal with aspects of traditional input and output. Chapter 10, Input and Output details the rules for reading and writing files (don’t skip this if you think files are boring; you’ll need some of this information in later chapters: you’ll read and write on serial or parallel ports in this chapter, and on a socket-based network connection in Chapter 13, Network Clients!). Chapter 11, Directory and Filesystem Operations shows you everything else about files—such as finding their size and last-modified time—and about reading and modifying directories, creating temporary files, and renaming files on disk.

Chapter 12, Media: Graphics, Audio, Video leads us into the GUI development side of things. This chapter is a mix of the lower-level details (such as drawing graphics and setting fonts and colors), and very high-level activities (such as controlling a video clip or movie). In Chapter 14, Graphical User Interfaces, I cover the higher-level aspects of a GUI, such as buttons, labels, menus, and the like—the GUI’s predefined components. Once you have a GUI (really, before you actually write it), you’ll want to read Chapter 15, Internationalization and Localization so your programs can work as well in Akbar, Afghanistan, Algiers, Amsterdam, and Angleterre as they do in Alberta, Arkansas, and Alabama.

Because Java was originally promulgated as “the programming language for the Internet,” it’s only fair that we spend some of our time on networking in Java. Chapter 13, Network Clients covers the basics of network programming from the client side, focusing on sockets. For the third edition, Chapter 13, Network Clients has been refocused from applets and web clients to emphasize web service clients instead. Today so many applications need to access a web service, primarily RESTful web services, that this seemed to be necessary. We’ll then move to the server side in Chapter 16, Server-Side Java, wherein you’ll learn some server-side programming techniques.

Programs on the Net often need to generate or process electronic mail, so Chapter 17, Java and Electronic Mail covers this topic.

Chapter 18, Database Access covers the essentials of the higher-level database access (JPA and Hibernate) and the lower-level Java Database Connectivity (JDBC), showing how to connect to local or remote relational databases, store and retrieve data, and find out information about query results or about the database.

One simple text-based representation for data interchange is JSON, the JavaScript Object Notation. Chapter 19, Processing JSON Data describes the format and some of the many APIs that have emerged to deal with it.

Another textual form of storing and exchanging data is XML. Chapter 20, Processing XML discusses XML’s formats and some operations you can apply using SAX and DOM, two standard Java APIs.

Chapter 21, Packages and Packaging shows how to create packages of classes that work together. This chapter also talks about “deploying” or distributing and installing your software.

Chapter 22, Threaded Java tells you how to write classes that appear to do more than one thing at a time and let you take advantage of powerful multiprocessor hardware.

Chapter 23, Reflection, or “A Class Named Class” lets you in on such secrets as how to write API cross-reference documents mechanically (“become a famous Java book author in your spare time!”) and how web servers are able to load any old Servlet—never having seen that particular class before—and run it.

Sometimes you already have code written and working in another language that can do part of your work for you, or you want to use Java as part of a larger package. Chapter 24, Using Java with Other Languages shows you how to run an external program (compiled or script) and also interact directly with “native code” in C/C++ or other languages.

There isn’t room in an 800-page book for everything I’d like to tell you about Java. The Afterword presents some closing thoughts and a link to my online summary of Java APIs that every Java developer should know about.

Finally, Appendix A gives the storied history of Java in a release-by-release timeline, so whatever version of Java you learned, you can jump in here and get up to date quickly.

No two programmers or writers will agree on the best order for presenting all the Java topics. To help you find your way around, I’ve included extensive cross-references, mostly by recipe number.

Platform Notes

Java has gone through many major versions as discussed in Appendix A. This book is aimed at the Java 7 and 8 platforms. By the time of publication, I expect that all Java projects in development will be using Java 6 or 7, with a few stragglers wedded to earlier versions for historical reasons (note that Java 6 has been in “end of life” status for about a year prior to this edition’s publication). I have compiled all the code in the javasrc archive on several combinations of operating systems and Java versions to test this code for portability.

The Java API consists of two parts: core APIs and noncore APIs. The core is, by definition, what’s included in the JDK that you download free from the Java website. Noncore is everything else. But even this “core” is far from tiny: it weighs in at around 50 packages and well over 3,000 public classes, averaging around a dozen public methods each. Programs that stick to this core API are reasonably assured of portability to any standard Java platform.

Java’s noncore APIs are further divided into standard extensions and nonstandard extensions. All standard extensions have package names beginning with javax. But note that not all packages named javax are extensions: javax.swing and its subpackages—the Swing GUI packages—used to be extensions, but are now core. A Java licensee (such as Apple or IBM) is not required to implement every standard extension, but if it does, the interface of the standard extension should be adhered to. This book calls your attention to any code that depends on a standard extension. Little

code here depends on nonstandard extensions, other than code listed in the book itself. My own package, com.darwinsys, contains some utility classes used here and there; you will see an import for this at the top of any file that uses classes from it.

In addition, two other platforms, Java ME and Java EE, are standardized. Java Micro Edition (Java ME) is concerned with small devices such as handhelds, cell phones, fax machines, and the like. Within Java ME are various “profiles” for different classes of devices. At the other end, the Java Enterprise Edition (Java EE) is concerned with building large, scalable, distributed applications. Servlets, JavaServer Pages, JavaServer Faces, CORBA, RMI, JavaMail, Enterprise JavaBeans (EJBs), Transactions, and other APIs are part of Java EE. Java ME and Java EE packages normally begin with “javax” because they are not core packages. This book does not cover these at all, but includes a few of the EE APIs that are also useful on the client side, such as JavaMail. As mentioned earlier, coverage of Servlets and JSPs from the first edition of this book has been removed because there is now a Java Servlet and JSP Cookbook.

Speaking of cell phones and mobile devices, you probably know that Android uses Java as its language. What is comforting to Java developers is that Android also uses most of the core Java API, except for Swing and AWT, for which it provides Android-specific replacements. The Java developer who wants to learn Android may consider looking at my Android Cookbook, or the book’s website.

Java Books

A lot of useful information is packed into this book. However, due to the breadth of topics, it is not possible to give book-length treatment to any one topic. Because of this, the book also contains references to many websites and other books. This is in keeping with my target audience: the person who wants to learn more about Java.

O’Reilly publishes, in my opinion, the best selection of Java books on the market. As the API continues to expand, so does the coverage. Check out the latest versions and ordering information from O’Reilly’s collection of Java books; you can buy them at most bookstores, both physical and virtual. You can also read them online through Safari, a paid subscription service. And, of course, most are now available in ebook format; O’Reilly eBooks are DRM free so you don’t have to worry about their copy-protection scheme locking you into a particular device or system, as you do with certain other publishers. Though many books are mentioned at appropriate spots in the book, a few deserve special mention here.

First and foremost, David Flanagan’s Java in a Nutshell (O’Reilly) offers a brief overview of the language and API and a detailed reference to the most essential packages. This is handy to keep beside your computer. Head First Java offers a much more whimsical introduction to the language and is recommended for the less experienced developer.

A definitive (and monumental) description of programming the Swing GUI is Java Swing by Marc Loy, Robert Eckstein, Dave Wood, James Elliott, and Brian Cole (O’Reilly).

Java Virtual Machine, by Jon Meyer and Troy Downing (O’Reilly), will intrigue the person who wants to know more about what’s under the hood. This book is out of print but can be found used and in libraries.

Java Network Programming and Java I/O, both by Elliotte Rusty Harold (O’Reilly), are also useful references.

For Java Database work, Database Programming with JDBC and Java by George Reese, and Pro JPA 2: Mastering the Java Persistence API by Mike Keith and Merrick Schincariol (Apress), are recommended.

Although this book doesn’t have much coverage of the Java EE, I’d like to mention two books on that topic:

- Arun Gupta’s Java EE 7 Essentials covers the latest incarnation of the Enterprise Edition.

- Adam Bien’s Real World Java EE Patterns: Rethinking Best Practices offers useful insights in designing and implementing an Enterprise application.

You can find many more at the O’Reilly website.

Before building and releasing a GUI application you should read Sun’s official Java Look and Feel Design Guidelines (Addison-Wesley). This work presents the views of the human factors and user-interface experts at Sun (before the Oracle takeover) who worked with the Swing GUI package since its inception; they tell you how to make it work well.

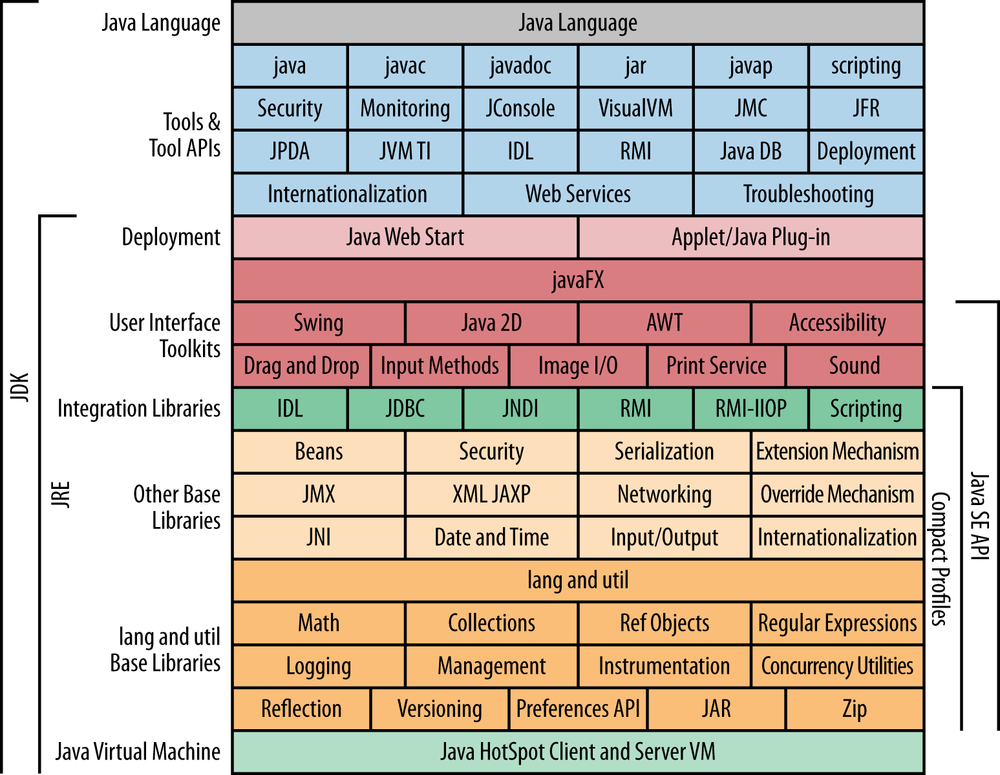

Finally, although it’s not a book, Oracle has a great deal of Java information on the Web. Part of this web page is a large diagram showing all the components of Java in a “conceptual diagram.” An early version of this is shown in Figure 1; each colored box is a clickable link to details on that particular technology. Note the useful “Java SE API” link at the right, which takes you to the javadoc pages for the entire Java SE API.

General Programming Books

Donald E. Knuth’s The Art of Computer Programming has been a source of inspiration to generations of computing students since its first publication by Addison-Wesley in 1968. Volume 1 covers Fundamental Algorithms, Volume 2 is Seminumerical Algorithms, and Volume 3 is Sorting and Searching. The remaining four volumes in the projected series are still not completed. Although his examples are far from Java (he invented a hypothetical assembly language for his examples), many of his discussions of algorithms—of how computers ought to be used to solve real problems—are as relevant today as they were years ago.[4]

Though its code examples are quite dated now, the book The Elements of Programming Style, by Kernighan and Plauger, set the style (literally) for a generation of programmers with examples from various structured programming languages. Kernighan and Plauger also wrote a pair of books, Software Tools and Software Tools in Pascal, which demonstrated so much good advice on programming that I used to advise all programmers to read them. However, these three books are dated now; many times I wanted to write a follow-on book in a more modern language, but instead defer to The Practice of Programming, Brian’s follow-on—cowritten with Rob Pike—to the Software Tools series. This book continues the Bell Labs (now part of Lucent) tradition of excellence in software textbooks. In Parsing Comma-Separated Data, I have even adapted one bit of code from their book.

See also The Pragmatic Programmer by Andrew Hunt and David Thomas (Addison-Wesley).

Design Books

Peter Coad’s Java Design (PTR-PH/Yourdon Press) discusses the issues of object-oriented analysis and design specifically for Java. Coad is somewhat critical of Java’s implementation of the observable-observer paradigm and offers his own replacement for it.

One of the most famous books on object-oriented design in recent years is Design Patterns, by Gamma, Helm, Johnson, and Vlissides (Addison-Wesley). These authors are often collectively called “the gang of four,” resulting in their book sometimes being referred to as “the GoF book.” One of my colleagues called it “the best book on object-oriented design ever,” and I agree; at the very least, it’s among the best.

Refactoring, by Martin Fowler, covers a lot of “coding cleanups” that can be applied to code to improve readability and maintainability. Just as the GoF book introduced new terminology that helps developers and others communicate about how code is to be designed, Fowler’s book provided a vocabulary for discussing how it is to be improved. But this book may be less useful than others; many of the “refactorings” now appear in the Refactoring Menu of the Eclipse IDE (see Compiling, Running, and Testing with an IDE).

Two important streams of methodology theories are currently in circulation. The first is collectively known as Agile Methods, and its best-known members are Scrum and Extreme Programming (XP). XP (the methodology, not last year’s flavor of Microsoft’s OS) is presented in a series of small, short, readable texts led by its designer, Kent Beck. The first book in the XP series is Extreme Programming Explained. A good overview of all the Agile methods is Highsmith’s Agile Software Development Ecosystems.

Another group of important books on methodology, covering the more traditional object-oriented design, is the UML series led by “the Three Amigos” (Booch, Jacobson, and Rumbaugh). Their major works are the UML User Guide, UML Process, and others. A smaller and more approachable book in the same series is Martin Fowler’s UML Distilled.

Conventions Used in This Book

This book uses the following conventions.

Programming Conventions

I use the following terminology in this book. A program means any unit of code that can be run: an applet, a servlet, or an application. An applet is a Java program for use in a browser. A servlet is a Java component for use in a server, normally via HTTP. An application is any other type of program. A desktop application (a.k.a. client) interacts with the user. A server program deals with a client indirectly, usually via a network connection (and usually HTTP/HTTPS these days).

The examples shown are in two varieties. Those that begin with zero or more import statements, a javadoc comment, and a public class statement are complete examples. Those that begin with a declaration or executable statement, of course, are excerpts. However, the full versions of these excerpts have been compiled and run, and the online source includes the full versions.

Recipes are numbered by chapter and number, so, for example, Providing Callbacks via Interfaces refers to the fifth recipe in Chapter 8.

Typesetting Conventions

The following typographic conventions are used in this book:

- Italic

- Used for commands, filenames, and example URLs. It is also used to define new terms when they first appear in the text.

-

Constant width - Used in code examples to show partial or complete Java source code program listings. It is also used for class names, method names, variable names, and other fragments of Java code.

-

Constant width bold - Used for user input, such as commands that you type on the command line.

-

Constant width italic - Shows text that should be replaced with user-supplied values or by values determined by context.

Note

This element signifies a general note.

|

This icon indicates by its single digit the minimum Java platform required to use the API discussed in a given recipe (you may need Java 7 to compile the example code, even if it’s not marked with a 7 icon). Only Java 6, 7, and 8 APIs are so denoted; anything earlier is assumed to work on any JVM that is still being used to develop code. Nobody should be using Java 5 (or anything before it!) for anything, and nobody should be doing new development in Java 6. If you are: it’s time to move on!

Code Examples

Many programs are accompanied by an example showing them in action, run from the command

line. These will usually show a prompt ending in either $ for Unix or > for

Windows, depending on what type of computer I was using that day. Text before this prompt

character can be ignored; it may be a pathname or a hostname, again depending on the system.

These will usually also show the full package name of the class because Java requires this when starting a program from the command line. This has the side effect of reminding you which subdirectory of the source repository to find the source code in, so this will not be pointed out explicitly very often.

We appreciate, but do not require, attribution. An attribution usually includes the title, author, publisher, and ISBN. For example: “Java Cookbook by Ian F. Darwin (O’Reilly). Copyright 2014 RejmiNet Group, Inc., 978-1-449-33704-9.”

If you feel your use of code examples falls outside fair use or the permission given above, feel free to contact us at permissions@oreilly.com.

Safari® Books Online

Note

Safari Books Online is an on-demand digital library that delivers expert content in both book and video form from the world’s leading authors in technology and business.

Technology professionals, software developers, web designers, and business and creative professionals use Safari Books Online as their primary resource for research, problem solving, learning, and certification training.

Safari Books Online offers a range of product mixes and pricing programs for organizations, government agencies, and individuals. Subscribers have access to thousands of books, training videos, and prepublication manuscripts in one fully searchable database from publishers like O’Reilly Media, Prentice Hall Professional, Addison-Wesley Professional, Microsoft Press, Sams, Que, Peachpit Press, Focal Press, Cisco Press, John Wiley & Sons, Syngress, Morgan Kaufmann, IBM Redbooks, Packt, Adobe Press, FT Press, Apress, Manning, New Riders, McGraw-Hill, Jones & Bartlett, Course Technology, and dozens more. For more information about Safari Books Online, please visit us online.

Comments and Questions

As mentioned earlier, I’ve tested all the code on at least one of the reference platforms, and most on several. Still, there may be platform dependencies, or even bugs, in my code or in some important Java implementation. Please report any errors you find, as well as your suggestions for future editions, by writing to:

| O’Reilly Media, Inc. |

| 1005 Gravenstein Highway North |

| Sebastopol, CA 95472 |

| 800-998-9938 (in the United States or Canada) |

| 707-829-0515 (international or local) |

| 707-829-0104 (fax) |

We have a web page for this book, where we list errata, examples, and any additional information. You can access this page at http://bit.ly/java-cookbook-3e.

To comment or ask technical questions about this book, send email to bookquestions@oreilly.com.

For more information about our books, courses, conferences, and news, see our website at http://www.oreilly.com.

Find us on Facebook: http://facebook.com/oreilly

Follow us on Twitter: http://twitter.com/oreillymedia

Watch us on YouTube: http://www.youtube.com/oreillymedia

The O’Reilly site lists errata. You’ll also find the source code for all the Java code examples to download; please don’t waste your time typing them again! For specific instructions, see Downloading and Using the Code Examples.

Acknowledgments

I wrote in the Afterword to the first edition that “writing this book has been a humbling experience.” I should add that maintaining it has been humbling, too. While many reviewers and writers have been lavish with their praise—one very kind reviewer called it “arguably the best book ever written on the Java programming language”—I have been humbled by the number of errors and omissions in the first edition. In preparing this edition, I have endeavored to correct these.

My life has been touched many times by the flow of the fates bringing me into contact with the right person to show me the right thing at the right time. Steve Munro, with whom I’ve long since lost touch, introduced me to computers—in particular an IBM 360/30 at the Toronto Board of Education that was bigger than a living room, had 32 or 64K (not M or G!) of memory, and had perhaps the power of a PC/XT. Herb Kugel took me under his wing at the University of Toronto while I was learning about the larger IBM mainframes that came later. Terry Wood and Dennis Smith at the University of Toronto introduced me to mini- and micro-computers before there was an IBM PC. On evenings and weekends, the Toronto Business Club of Toastmasters International and Al Lambert’s Canada SCUBA School allowed me to develop my public speaking and instructional abilities. Several people at the University of Toronto, but especially Geoffrey Collyer, taught me the features and benefits of the Unix operating system at a time when I was ready to learn it.

Greg Davidson of UCSD taught the first Learning Tree course I attended and welcomed me as a Learning Tree instructor. Years later, when the Oak language was about to be released on Sun’s website, Greg encouraged me to write to James Gosling and find out about it. James’ reply (cited near the beginning of this Preface) that the lawyers had made them rename the language to Java and that it was “just now” available for download, is the prized first entry in my saved Java mailbox. Mike Rozek took me on as a Learning Tree course author for a Unix course and two Java courses. After Mike’s departure from the company, Francesco Zamboni, Julane Marx, and Jennifer Urick in turn provided product management of these courses. When that effort ran out of steam, Jennifer also arranged permission for me to “reuse some code” in this book that had previously been used in my Java course notes. Finally, thanks to the many Learning Tree instructors and students who showed me ways of improving my presentations. I still teach for “The Tree” and recommend their courses for the busy developer who wants to zero in on one topic in detail over four days. You can also visit their website.

Closer to this project, Tim O’Reilly believed in “the little Lint book” when it was just a sample chapter, enabling my early entry into the rarefied circle of O’Reilly authors. Years later, Mike Loukides encouraged me to keep trying to find a Java book idea that both he and I could work with. And he stuck by me when I kept falling behind the deadlines. Mike also read the entire manuscript and made many sensible comments, some of which brought flights of fancy down to earth. Jessamyn Read turned many faxed and emailed scratchings of dubious legibility into the quality illustrations you see in this book. And many, many other talented people at O’Reilly helped put this book into the form in which you now see it.

Third Edition

As always, this book would be nowhere without the wonderful support of so many people at O’Reilly. Meghan Blanchette, Sarah Schneider, Adam Witwer, Melanie Yarbrough, and the many production people listed on the copyright page all played a part in getting this book ready for you to read. The code examples are now dynamically included (so updates get done faster) rather than pasted in; my son and Haskell developer Benjamin Darwin, helped meet the deadline by converting almost the entire code base to O’Reilly’s newest “include” mechanism, and by resolving a couple of other non-Java presentation issues; he also helped make Chapter 9 clearer and more functional. My reviewer, Alex Stangl, read the manuscript and went far above the call of duty, making innumerable helpful suggestions, even finding typos that had been present in previous editions! Helpful suggestions on particular sections were made by Benjamin Darwin, Mark Finkov, Igor Savin, and anyone I’ve forgotten to mention: I thank you all!

And again a thanks to all the readers who found errata and suggested improvements. Every new edition is better for the efforts of folks like you, who take the time and trouble to report that which needs reporting!

Second Edition

I wish to express my heartfelt thanks to all who sent in both comments and criticisms of the book after the first English edition was in print. Special mention must be made of one of the book’s German translators,[5] Gisbert Selke, who read the first edition cover to cover during its translation and clarified my English. Gisbert did it all over again for the second edition and provided many code refactorings, which have made this a far better book than it would be otherwise. Going beyond the call of duty, Gisbert even contributed one recipe (Marrying Java and Perl) and revised some of the other recipes in the same chapter. Thank you, Gisbert! The second edition also benefited from comments by Jim Burgess, who read large parts of the book. Comments on individual chapters were received from Jonathan Fuerth, Kim Fowler, Marc Loy, and Mike McCloskey. My wife, Betty, and teenaged children each proofread several chapters as well.

The following people contributed significant bug reports or suggested improvements from the first edition: Rex Bosma, Rod Buchanan, John Chamberlain, Keith Goldman, Gilles-Philippe Gregoire, B. S. Hughes, Jeff Johnston, Rob Konigsberg, Tom Murtagh, Jonathan O’Connor, Mark Petrovic, Steve Reisman, Bruce X. Smith, and Patrick Wohlwend. My thanks to all of them, and my apologies to anybody I’ve missed.

My thanks to the good guys behind the O’Reilly “bookquestions” list for fielding so many questions. Thanks to Mike Loukides, Deb Cameron, and Marlowe Shaeffer for editorial and production work on the second edition.

First Edition

I also must thank my first-rate reviewers for the first edition, first and foremost my dear wife, Betty Cerar, who still knows more about the caffeinated beverage that I drink while programming than the programming language I use, but whose passion for clear expression and correct grammar has benefited so much of my writing during our life together. Jonathan Knudsen, Andy Oram, and David Flanagan commented on the outline when it was little more than a list of chapters and recipes, and yet were able to see the kind of book it could become, and to suggest ways to make it better. Learning Tree instructor Jim Burgess read most of the first edition with a very critical eye on locution, formulation, and code. Bil Lewis and Mike Slinn (mslinn@mslinn.com) made helpful comments on multiple drafts of the book. Ron Hitchens (ron@ronsoft.com) and Marc Loy carefully read the entire final draft of the first edition. I am grateful to Mike Loukides for his encouragement and support throughout the process. Editor Sue Miller helped shepherd the manuscript through the somewhat energetic final phases of production. Sarah Slocombe read the XML chapter in its entirety and made many lucid suggestions; unfortunately, time did not permit me to include all of them in the first edition. Each of these people made this book better in many ways, particularly by suggesting additional recipes or revising existing ones. The faults that remain are my own.

No book on Java would be complete without a quadrium[6] of thanks to James Gosling for inventing the first Unix Emacs, the sc spreadsheet, the NeWS window system, and Java. Thanks also to his employer Sun Microsystems (before they were taken over by Oracle) for creating not only the Java language but an incredible array of Java tools and API libraries freely available over the Internet.

Thanks to Tom and Nathan for the Perl Cookbook. Without them I might never have come up with the format for this book.

Willi Powell of Apple Canada provided Mac OS X access in the early days of OS X; I have since worn out an Apple notebook or two of my own. Thanks also to Apple for basing OS X on BSD Unix, making Apple the world’s largest-volume commercial Unix company in the desktop environment (Google’s Android is way larger than OS X in terms of unit shipments, but it’s based on Linux and isn’t a big player in the desktop).

To each and every one of you, my sincere thanks.

Book Production Software

I used a variety of tools and operating systems in preparing, compiling, and testing the first edition. The developers of OpenBSD, “the proactively secure Unix-like system,” deserve thanks for making a stable and secure Unix clone that is also closer to traditional Unix than other freeware systems. I used the vi editor (vi on OpenBSD and vim on Windows) while inputting the original manuscript in XML, and Adobe FrameMaker to format the documents. Each of these is an excellent tool in its own way, but I must add a caveat about FrameMaker. Adobe had four years from the release of OS X until I started the next revision cycle of this book, during which it could have produced a current Macintosh version of FrameMaker. It chose not do so, requiring me to do that revision in the increasingly ancient Classic environment. Strangely enough, its Mac sales of FrameMaker dropped steadily during this period, until, during the final production of the second edition, Adobe officially announced that it would no longer be producing any Macintosh versions of this excellent publishing software, ever. I do not know if I can ever forgive Adobe for destroying what was arguably the world’s best documentation system.

Because of this, the crowd-sourced Android Cookbook that I edited was not prepared with Adobe’s FrameMaker, but instead used XML DocBook (generated from Wiki markup on a Java-powered website that I wrote for the purpose) and a number of custom tools provided by O’Reilly’s tools group.

The third edition of Java Cookbook was formatted in AsciiDoc and the newer, faster AsciiDoctor, and brought to life on the publishing interface of O’Reilly’s Atlas.

[1] Editor’s note: the “other Oak” that triggered this renaming was not a computer language, as is sometimes supposed, but Oak Technology, makers of video cards and the cdrom.sys file that was on every DOS/Windows PC at one point.

[2] One of the world’s leading high-tech, vendor-independent training companies; see http://www.learningtree.com/.

[3] Well, not completely. See the Java Puzzlers books by Joshua Bloch and Neal Gafter for the actual quirks.

[4] With apologies for algorithm decisions that are less relevant today given the massive changes in computing power now available.

[5] The first edition is available today in English, German, French, Polish, Russian, Korean, Traditional Chinese, and Simplified Chinese. My thanks to all the translators for their efforts in making the book available to a wider audience.

[6] It’s a good thing he only invented four major technologies, not five, or I’d have to rephrase that to avoid infringing on an Intel trademark.

Get Java Cookbook, 3rd Edition now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.