Spreadsheet Basics

You use Excel, of course, to make a spreadsheet—an electronic ledger book composed of rectangles, known as cells, laid out in a grid (see Figure 12-1). As you type numbers into the rectangular cells, the program can automatically perform any number of calculations on them. And although the spreadsheet’s forte is working with numbers, you can use them for text, too; because they’re actually a specialized database, you can turn spreadsheets into schedules, calendars, wedding registries, address books, and other simple text databases.

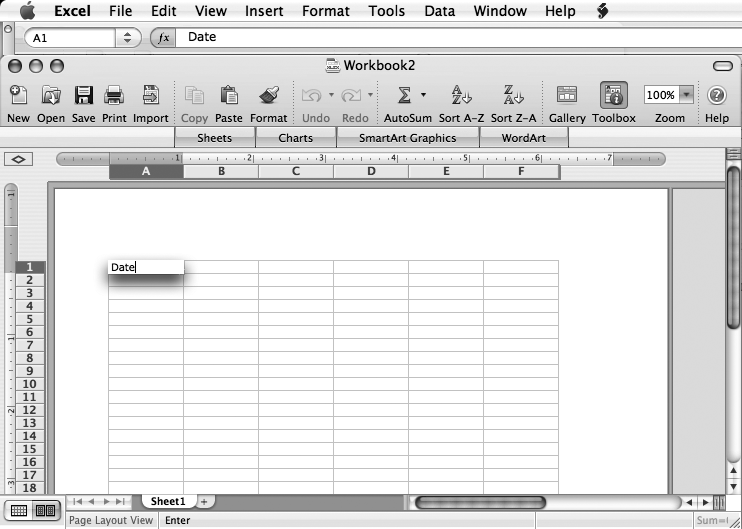

Figure 12-1. Excel 2008 has all the usual Mac OS X doodads, like close, minimize, and zoom buttons and a status bar. In the status area at the bottom left, Excel tells you what it thinks is happening—in this case, Enter indicates the active cell (A1) is being edited.

Opening a Spreadsheet

A new Excel document, called a workbook, is made up of one or more pages called worksheets. (You’ll find more on the workbook/worksheet distinction in Chapter 14.) Each worksheet is an individual spreadsheet, with lettered columns and numbered rows providing coordinates to refer to the cells in the grid.

You can create a plain-Jane Excel workbook by selecting File → New Workbook (⌘-N), or you can use the Office Project Gallery (File → Project Gallery). If you happen to find a template that fits what you’re trying to do, like planning a budget, the Gallery ...

Get Office 2008 for Macintosh: The Missing Manual now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.