Preface

Unlike the stereotypical wedding dress, it wasâto use a technical termâelegant, like a computer algorithm that achieves an impressive outcome with just a few lines of code.

Graeme Simsion, The Rosie Effect

Welcome to Elegant SciPy. Weâre going to spend rather a lot of time focusing on the âSciPyâ bit of the title, so letâs take a moment to reflect on the âElegantâ bit. There are plenty of manuals, tutorials, and documentation websites out there that describe the SciPy library. Elegant SciPy goes further. More than just teaching you how to write code that works, we will inspire you to write code that rocks!

In The Rosie Effect (hilarious book; go read its prequel The Rosie Project when youâre done with Elegant SciPy), Graeme Simsion twists the conventions of the word âelegantâ around. Most would use it to describe the visual simplicity, style, and grace of, say, the first iPhone. Instead Graeme Simsionâs hero, Don Tillman, uses a computer algorithm to define elegance. We hope that you will understand exactly what he means after reading this book; that you will read or write a piece of elegant code, and feel calmed in the glow of its beauty and grace. (Note: The authors may be prone to hyperbole.)

A good piece of code just feels right. When you look at it, its intent is clear, it is often concise (but not so concise as to be obscure), and it is efficient at executing the task at hand. For the authors, the joy of analyzing elegant code lies in the lessons hidden within, and the way it inspires us to be creative in how we approach new coding problems.

Ironically, creativity can also tempt us to show off cleverness at the expense of the reader, and write obtuse code that is hard to understand. PEP8 (the Python style guide) and PEP20 (the Zen of Python) remind us that âcode is read much more often than it is writtenâ and therefore âreadability counts.â

The conciseness of elegant code comes through abstraction and the judicious use of functions, not just through packing in a bunch of nested function calls. It may take a minute or two to grok, but it should ultimately provide a crisp, âah-ha!â moment of understanding. Once you know the various components of the code, its correctness should be obvious. This can be aided by clear variable and function names, and carefully crafted comments that explain the code, rather than merely describe it.

In the New York Times, software engineer J. Bradford Hipps recently argued that âto write better code, [one should] read Virginia Woolfâ:

As a practice, software development is far more creative than algorithmic.

The developer stands before her source code editor in the same way the author confronts the blank page. [â¦] They may also share a healthy impatience for the ways things âhave always been doneâ and a generative desire to break conventions. When the module is finished or the pages complete, their quality is judged against many of the same standards: elegance, concision, cohesion; the discovery of symmetries where none were seen to exist. Yes, even beauty.

This is the position we take in this book.

Now that weâve dealt with the âelegantâ part of the title, letâs come back to the âSciPy.â

Depending on context, âSciPyâ can mean a software library, an ecosystem, or a community. Part of what makes SciPy great is that it has excellent online documentation and tutorials, rendering Just Another Reference book pointless; instead, Elegant SciPy wants to present the best code built with SciPy.

The code we have chosen highlights clever, elegant uses of advanced features of NumPy, SciPy, and related libraries. The beginning reader will learn to apply these libraries to real-world problems using beautiful code. And we use real scientific data to motivate our examples.

Like SciPy itself, we wanted Elegant SciPy to be driven by the community. Weâve taken many of our examples from working code found in the wider scientific Python ecosystem, selecting them for their illustration of the principles of elegant code we outlined above.

Who Is This Book For?

Elegant SciPy is intended to inspire you to take your Python to the next level. You will learn SciPy by example, from the very best code.

Before starting, you should at least have seen Python, and know about variables, functions, loops, and maybe a bit of NumPy. You might have even honed your Python skills with advanced material, such as Fluent Python. If this doesnât describe you, you should start with some beginner Python tutorials, such as Software Carpentry, before continuing with this book.

But perhaps you donât know whether the âSciPy stackâ is a library or a menu item from the International House of Pancakes, and you arenât sure about best practices. Perhaps you are a scientist who has read some Python tutorials online, and have downloaded some analysis scripts from another lab or a previous member of your own lab, and have fiddled with them. And you might think that you are more or less alone when you learn to code SciPy. You are not.

As we progress, we will teach you how to use the internet as your reference. And we will point you to the mailing lists, repositories, and conferences where you will meet like-minded scientists who are a little further in their journey than you.

This is a book that you will read once, but may return to for inspiration (and maybe to admire some elegant code snippets!).

Why SciPy?

The NumPy and SciPy libraries make up the core of the Scientific Python ecosystem. The SciPy software library implements a set of functions for processing scientific data, such as statistics, signal processing, image processing, and function optimization. SciPy is built on top of NumPy, the Python numerical array computation library. Building on NumPy and SciPy, an entire ecosystem of apps and libraries has grown dramatically over the past few years, spanning a broad spectrum of disciplines that includes astronomy, biology, meteorology and climate science, and materials science, among others.

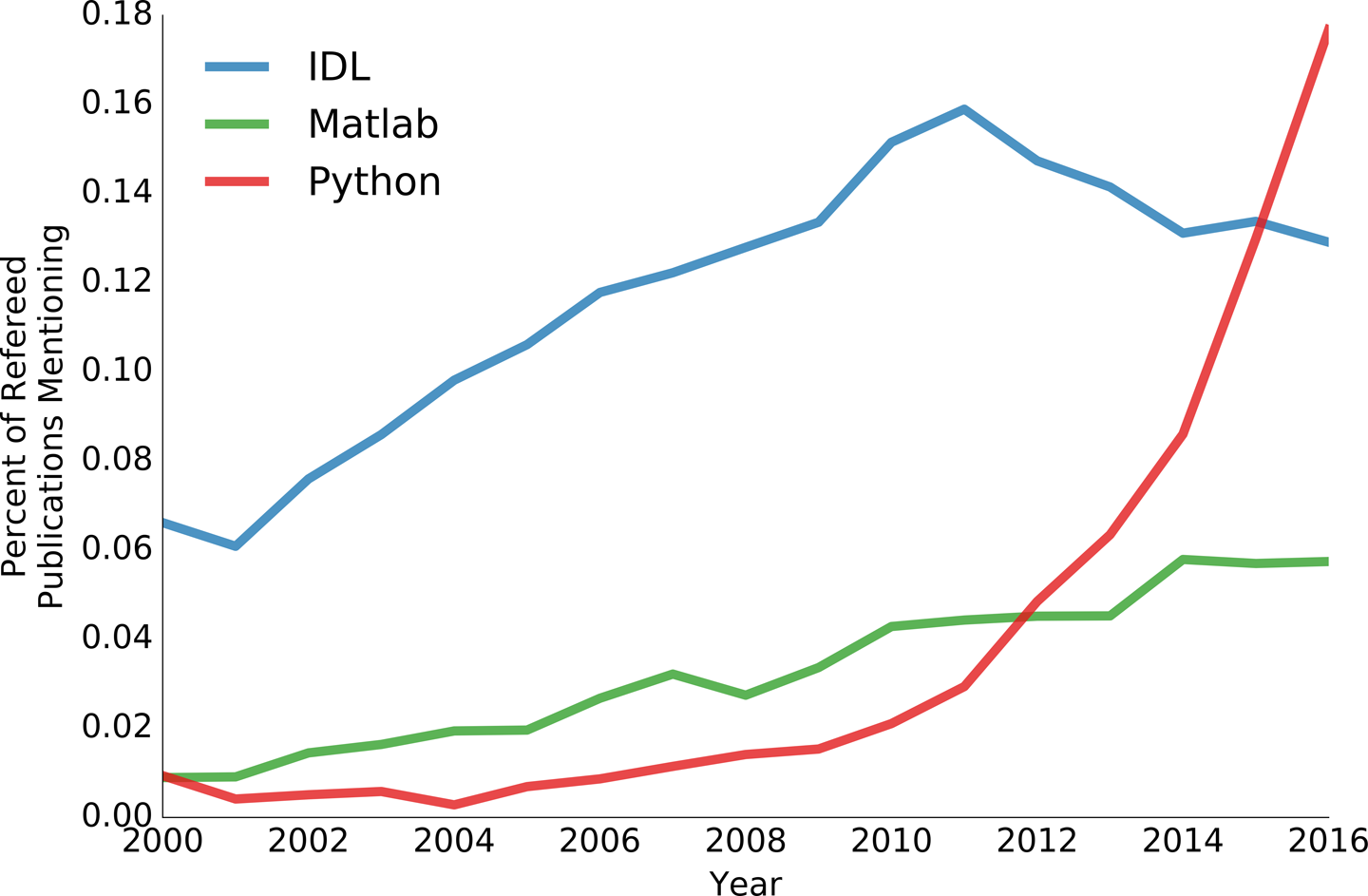

This growth shows no sign of abating. In 2014, Thomas Robitaille and Chris Beaumont documented Pythonâs growing use in astronomy. Hereâs what we found when we updated their plot in the second half of 2016:

It is clear that SciPy and related libraries will be driving much of scientific data analysis for years to come.

As another example, the Software Carpentry organization, which teaches computational skills to scientists, most often using Python, currently cannot keep up with demand.

What Is the SciPy Ecosystem?

SciPy (pronounced âSigh Pieâ) is a Python-based ecosystem of open-source software for mathematics, science, and engineering.

The SciPy ecosystem is a loosely defined collection of Python packages. In Elegant SciPy, we will meet many of its main players:

- NumPy is the foundation of scientific computing in Python. It provides efficient numeric arrays and wide support for numerical computation, including linear algebra, random numbers, and Fourier transforms. NumPyâs killer feature is its âN-dimensional array,â or ndarray. These data structures store numeric values efficiently and define a grid in any number of dimensions (more about this later).

- SciPy, the library, is a collection of efficient numerical algorithms for domains such as signal processing, integration, optimization, and statistics. These are wrapped in user-friendly interfaces.

- Matplotlib is a powerful package for plotting in two dimensions (and basic 3D). It draws its name from its Matlab-inspired syntax.

- IPython is an interactive interface for Python that allows you to quickly interact with your data and test ideas.

- The Jupyter notebook runs in your browser and allows the construction of rich documents that combine code, text, mathematical expressions, and interactive widgets.1 In fact, to produce this book, the text is converted to Jupyter notebooks and executed (that way, we know that all the examples execute correctly). Jupyter started out as an IPython extension, but now supports multiple languages, including Cython, Julia, R, Octave, Bash, Perl, and Ruby.

- pandas provides fast, columnar data structures in an easy-to-use package. It is particularly suited to working with labeled datasets such as tables or relational databases, and for managing time series data and sliding windows. pandas also has some handy data analysis tools for data parsing and cleaning, aggregation, and plotting.

- scikit-learn provides a unified interface to machine learning algorithms.

- scikit-image provides image analysis tools that integrate cleanly with the rest of the SciPy ecosystem.

There are many other Python packages that form part of the SciPy ecosystem, and we will see some of them too. Although this book will focus on NumPy and SciPy, the many surrounding packages are what make Python a powerhouse for scientific computing.

The Great Cataclysm: Python 2 Versus Python 3

In your Python travels, you may have already heard a few rumblings about which version of Python is better. You may have wondered why itâs not just the latest version. (Spoiler alert: it is.)

At the end of 2008, the Python core developers released Python 3, a major update to the language with better Unicode (international) text handling, type consistency, and streaming data handling, among other improvements. As Douglas Adams quipped2 about the creation of the Universe, âthis has made a lot of people very angry and been widely regarded as a bad move.â Thatâs because Python 2.6 or 2.7 code cannot usually be interpreted by Python 3 without at least some modification (though the changes are typically not too invasive).

There is always a tension between the march of progress and backward compatibility. In this case, the Python core team decided that a clean break was needed to eliminate some inconsistencies, especially in the underlying C API, and moved the language forward into the twenty-first century (Python 1.0 appeared in 1994, more than 20 years agoâa lifetime in the tech world).

Hereâs one way in which Python has improved in turning 3:

print "Hello World!" # Python 2 print statement

print("Hello World!") # Python 3 print function

Why cause such a fuss just to add some parentheses! Well, true, but what if you want to instead print to a different stream, such as standard error, the usual place for debugging information?

print >>sys.stderr, "fatal error" # Python 2

print("fatal error", file=sys.stderr) # Python 3

That change certainly seems more worthwhile; what is going on in the Python 2 version anyway? The authors donât rightly know.

Another change is the way Python 3 treats integer division, which is the way most humans treat division. (Note >>> indicates we are typing at the Python interactive shell.)

# Python 2 >>> 5 / 2 2 # Python 3 >>> 5 / 2 2.5

We were also pretty excited about the new @ matrix multiplication operator introduced in Python 3.5 in 2015. Check out Chapters 5 and 6 for some examples of this operator in use!

Possibly the biggest improvement in Python 3 is its support for Unicode, a way of encoding text that allows one to use not just the English alphabet, but any alphabet in the world. Python 2 allowed you to define a Unicode string, like so:

beta=u"β"

But in Python 3, everything is Unicode:

β=0.5(2*β)

1.0

The Python core team decided, rightly, that it was worth supporting characters from all languages as first-class citizens in Python code. This is especially true now, when most new coders are from non-English-speaking countries. For the sake of interoperability, we still recommend using English characters in most code, but this capability can come in handy, for example, in math-heavy Jupyter notebooks.

Tip

In the IPython terminal or in the Jupyter notebook, type a LaTeX symbol name followed by the Tab key to have it expanded to Unicode. For example, \beta<TAB> becomes β.

The Python 3 update also breaks a lot of existing 2.x code, and in some cases executes more slowly than before. Despite these frustrations, we encourage all users to upgrade as soon as possible (Python 2.x is now in maintenance only mode until 2020), since most issues have been addressed as the 3.x series has matured. Indeed, we use many new features from Python 3 in this book.

In this book, we use Python 3.6.

For more reading, see Ed Schofieldâs resource, Python-Future, and Nick Coghlanâs book-length guide to the transition.

SciPy Ecosystem and Community

SciPy is a major library with a lot of functionality. Together with NumPy, it is one of Pythonâs killer apps. It has launched a vast number of related libraries that build on this functionality, many of which youâll encounter throughout this book.

The creators of these libraries, and many of their users, gather at many events and conferences around the world. These include the yearly SciPy conference in Austin (USA), EuroSciPy, SciPy India, PyData, and others. We highly recommend attending one of these, and meeting the authors of the best scientific software in the Python world. If you canât get there, or simply want a taste of these conferences, many publish their talks online.

Free and Open Source Software (FOSS)

The SciPy community embraces open source software development. The source code for nearly all SciPy libraries is freely available to read, edit, and reuse by anyone.

If you want others to use your code, one of the best ways to achieve this is to make it free and open. If you use closed source software, but it doesnât do exactly what you want to achieve, youâre out of luck. You can email the developer and ask them to add a new feature (this often doesnât work!), or write new software yourself. If the code is open source, you can easily add or modify its functionality using the skills you learn from this book.

Similarly, if you find a bug in a piece of software, having access to the source code can make things a lot easier for both the user and the developer. Even if you donât quite understand the code, you can usually get a lot further along in diagnosing the problem, and help the developer with fixing it. It is usually a learning experience for everyone!

Open source, open science

In scientific programming, all of the above scenarios are extremely common and important: scientific software often builds on previous work, or modifies it in interesting ways. And, because of the pace of scientific publishing and progress, much code is not thoroughly tested before release, resulting in minor or major bugs.

Another great reason for making code open source is to promote reproducible research. Many of us have had the experience of reading a really cool paper, and then downloading the code to try it out on our own data, only we find that the executable isnât compiled for our system. Or we canât work out how to run it. Or it has bugs, missing features, or produces unexpected results. By making scientific software open source, we not only increase the quality of that software, but we make it possible to see exactly how the science was done. What assumptions were made, and even hard-coded? Open source helps to solve many of these issues. It also enables other scientists to build on the code of their peers, fostering new collaborations and speeding up scientific progress.

Open source licenses

If you want others to use your code, then you must license it. If you donât license your code, it is closed by default. Even if you publish your code (e.g., by placing it in a public GitHub repository), without a software license, no one is allowed to use, edit, or redistribute your code.

When choosing among the many license options, you must first decide what you want to allow people to do with your code. Do you want people to be able to sell your code for profit? Or sell software that uses your code? Or do you want to restrict your code to be used only in free software?

There are two broad categories of FOSS licenses:

- Permissive

- Copy-left

A permissive license means you are giving anyone the right to use, edit, and redistribute your code in any way that they like. This includes using your code as part of commercial software. Some popular choices in this category include the MIT and BSD licenses. The SciPy community has adopted the New BSD License (also called âModified BSDâ or â3-clause BSDâ). Using such a license means receiving many code contributions from a wide array of people, including many in industry and startups.

Copy-left licenses also allow others to use, edit, and redistribute your code. These licenses, however, also prescribe that derived code must be distributed under a copy-left license. In this way, copy-left licenses restrict what users can do with the code.

The most popular copy-left license is the GNU Public License, or GPL. The main disadvantage to using a copy-left license is that you are often putting your code off-limits to any potential users or contributors from the private sector. And this could include your future self! This can substantially reduce your user base and thus the success of your software. In science, this could mean fewer citations.

For more help choosing a license, see the Choose a License website. For licensing in a scientific context, we recommend âThe Whys and Hows of Licensing Scientific Code,â a blog post by Jake VanderPlas, Director of Research in the Physical Sciences at the University of Washington, and all-around SciPy superstar. In fact, we quote Jake here to drive home the key points of software licensing:

â¦if you only take three pieces of information away from the article, let them be these:

- Always license your code. Unlicensed code is closed code, so any open license is better than none (but see #2).

- Always use a GPL-compatible license. GPL-compatible licenses ensure broad compatibility for your code, and include GPL, new BSD, MIT, and others (but see #3).

- Always use a permissive, BSD-style license. A permissive license such as new BSD or MIT is preferable to a copyleft license such as GPL or LGPL.

All the code in this book is available under the 3-Clause BSD license. Where we have sourced code snippets from other people, the code was generally under a permissive open license of some variety (although not necessarily BSD).

For your own code, we recommend that you follow the practices of your community. In scientific Python, this means 3-Clause BSD, while the R language community, for example, has adopted the GPL license.

GitHub: Taking Coding Social

Weâve talked a little about releasing your source code under an open source license. This will hopefully result in huge numbers of people downloading your code, using it, fixing bugs, and adding new features. Where will you put your code so people can find it? How will those bug fixes and features get back into your code? How will you keep track of all the issues and changes? You can imagine how this could get out of control quite quickly.

Enter GitHub.

GitHub is a website for hosting, sharing, and developing code. It is based on the Git version control software. There are some great resources to learn to use GitHub, such as Introducing GitHub by Peter Bell and Brent Beer. The vast majority of projects in the SciPy ecosystem are hosted on GitHub, so it is certainly worth learning to use it!

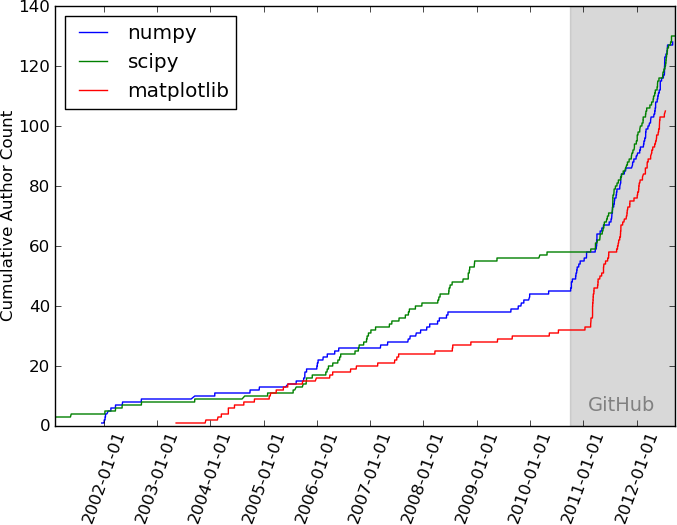

GitHub has had a massive effect on open source contributions. It did this by allowing users to publish code and collaborate for free. Anyone can come along and create a copy (called a fork) of the code and edit it to their heartâs content. They can eventually contribute those changes back into the original by creating a pull request. There are some nice features like managing issues and change requests, as well as the ability to determine who can directly edit your code. You can even keep track of edits, contributors, and other fun stats. There are a whole bunch of other great GitHub features, but we will leave many of them for you to discover and some for you to read in later chapters. In essence, GitHub has democratized software development (Figure P-1), and has substantially reduced the barrier to entry.

Figure P-1. The impact of GitHub (used with permission of the author, Jake VanderPlas)

Make Your Mark on the SciPy Ecosystem

As you gain more experience with SciPy and start using it for your research, you may find that a particular package is lacking a feature you need, or you think that you can do something more efficiently, or perhaps find a bug. When you reach this point, itâs time to start contributing to the SciPy ecosystem.

We strongly encourage you to try doing this. The community lives because people are willing to share their code and improve existing code. And, if we each contribute a little bit, together we build a lot. But, beyond any altruistic reasons for contributing, there are some very practical personal benefits. By engaging with the community you will become a better coder. Any code you contribute will be reviewed by others and you will receive feedback. As a side effect, you will learn how to use Git and GitHub, which are very useful tools for maintaining and sharing your own code. You may even find that interacting with the SciPy community provides you with a broader scientific network and surprising career opportunities.

We want you to think about being more than just a SciPy user. You are joining a community, and your work will make it a better place for all scientific coders.

A Touch of Whimsy with Your Py

In case you were worried that the SciPy community might be an imposing place for the newcomer, remember that it is made of people like you, scientists, usually with a great sense of humor.

In the land of Python, it is inevitable to find some Monty Python references. The package Airspeed Velocity measures your softwareâs speed (more on this later), and references the line, âwhat is the airspeed velocity of an unladen swallow?â from Monty Python and the Holy Grail.

Another amusingly titled package is âSux,â which allows you to use Python 2 packages from Python 3. This is a play on âsix,â which lets you use Python 3 syntax in Python 2, with a New Zealand accent. Sux syntax makes it less frustrating to use Python 2âonly packages after youâve moved to Python 3:

import sux

p = sux.to_use('my_py2_package')

In general, Python library names can be a riot, and we hope youâll enjoy your time coming up with some!

Getting Help

Our first step when we get stuck is to Google the task that we are trying to achieve, or the error message that we got. This generally leads us to Stack Overflow, an excellent question-and-answer site for programming. If you donât find what youâre looking for immediately, try generalizing your search terms to find someone who is having a similar problem.

Sometimes, you might actually be the first person to have this specific question (this is particularly likely when you are using a brand new package), but not all is lost! As mentioned above, the SciPy community is a friendly bunch, and can be found scattered around various parts of the interwebs. Your next point of call is to Google "<library name> mailing list,â and find an email list to ask for help. Library authors and power users read these regularly, and are very welcoming to newcomers. Note that it is common etiquette to subscribe to the list before posting. If you donât, it usually means someone will have to manually check that your email isnât spam before allowing it to be posted to the list. It may seem annoying to join yet another mailing list, but we highly recommend it: it is a great place to learn!

Installing Python

Throughout this book weâre going to assume that you have Python 3.6 (or later) and have all the required SciPy packages installed. We list all of the requirements and the versions we used in the environment.yml file packaged with the data for this book. The easiest way to get all of these components is to install conda, a tool for managing Python environments. You can then pass that environment.yml file to conda to install the right versions of everything in one go.

conda env create --name elegant-scipy -f path/to/environment.yml source activate elegant-scipy

See the bookâs GitHub repository for more details.

Accessing the Book Materials

All of the code and data shown in this book are available on our GitHub repository. In the README file in that repository, you will find instructions to build Jupyter notebooks from the markdown source files, which you can then run interactively using the data included in the repo.

Diving In

Weâve brought together some of the most elegant code offered up by the SciPy community. Along the way we are going to explore some real-world scientific problems that SciPy solves. This book is also a glimpse into a welcoming, collaborative scientific coding community that wants you to join in.

Welcome to Elegant SciPy.

Conventions Used in This Book

The following typographical conventions are used in this book:

- Italic

-

Indicates new terms, URLs, email addresses, filenames, and file extensions.

Constant width-

Used for program listings, as well as within paragraphs to refer to program elements such as variable or function names, databases, data types, environment variables, statements, and keywords.

Constant width bold-

Shows commands or other text that should be typed literally by the user.

Constant width italic-

Shows text that should be replaced with user-supplied values or by values determined by context.

Tip

This element signifies a tip or suggestion.

Note

This element signifies a general note.

Warning

This element indicates a warning or caution.

Use of Color

Some of the examples throughout indicate different colors, which is not visible in the print version of this book. Readers of the print book are encouraged to view the source notebooks at elegant-scipy.org.

Using Code Examples

Supplemental material (code examples, exercises, etc.) is available for download at https://github.com/elegant-scipy/elegant-scipy.

This book is here to help you get your job done. In general, if example code is offered with this book, you may use it in your programs and documentation. You do not need to contact us for permission unless youâre reproducing a significant portion of the code. For example, writing a program that uses several chunks of code from this book does not require permission. Selling or distributing a CD-ROM of examples from OâReilly books does require permission. Answering a question by citing this book and quoting example code does not require permission. Incorporating a significant amount of example code from this book into your productâs documentation does require permission.

We appreciate, but do not require, attribution. An attribution usually includes the title, author, publisher, and ISBN. For example: âElegant SciPy by Juan Nunez-Iglesias, Stéfan van der Walt, and Harriet Dashnow (OâReilly). Copyright 2017 Juan Nunez-Iglesias, Stéfan van der Walt, and Harriet Dashnow, 978-1-491-92287-3.â

If you feel your use of code examples falls outside fair use or the permission given above, feel free to contact us at permissions@oreilly.com.

OâReilly Safari

Note

Safari (formerly Safari Books Online) is a membership-based training and reference platform for enterprise, government, educators, and individuals.

Members have access to thousands of books, training videos, Learning Paths, interactive tutorials, and curated playlists from over 250 publishers, including OâReilly Media, Harvard Business Review, Prentice Hall Professional, Addison-Wesley Professional, Microsoft Press, Sams, Que, Peachpit Press, Adobe, Focal Press, Cisco Press, John Wiley & Sons, Syngress, Morgan Kaufmann, IBM Redbooks, Packt, Adobe Press, FT Press, Apress, Manning, New Riders, McGraw-Hill, Jones & Bartlett, and Course Technology, among others.

For more information, please visit http://oreilly.com/safari.

How to Contact Us

Please address comments and questions concerning this book to the publisher:

- OâReilly Media, Inc.

- 1005 Gravenstein Highway North

- Sebastopol, CA 95472

- 800-998-9938 (in the United States or Canada)

- 707-829-0515 (international or local)

- 707-829-0104 (fax)

To comment or ask technical questions about this book, send email to bookquestions@oreilly.com.

For more information about our books, courses, conferences, and news, see our website at http://www.oreilly.com.

Find us on Facebook: http://facebook.com/oreilly

Follow us on Twitter: http://twitter.com/oreillymedia

Watch us on YouTube: http://www.youtube.com/oreillymedia

Acknowledgments

We have to thank the many, many individuals who made essential contributions to this book. It would not have happened without your help.

First and foremost, we wish to thank the many contributors to the NumPy, SciPy, and related libraries. We hope we have done your amazing work justice in this book.

Next, the many contributors to the wider scientific Python ecosystem, including those who provided the foundation for several of our chapters: Vighnesh Birodkar, Matt Rocklin, and Warren Weckesser. We must also thank those whose contributions we were unable to include come press time. Your work inspired us and we hope to include it in future versions of the book. We also thank Nicolas Rougier for his many suggestions that we included as examples and exercises.

Others provided us with data and code that saved us hours of searching and sleuthing. We thank Lav Varshney for the original MATLAB code for spectral graph layout for the worm brain (Chapters 3 and 6), and Stefano Allesina for the St. Marks food web data (Chapter 6).

We are indebted to everyone who made corrections and suggestions while the book was in prerelease, including Bill Katz, Matthias Bussonnier, and Mark Hyun-ki Kim.

We thank our technical reviewers, Thomas Caswell, Nelle Varoquaux, Lav Varshney, and Greg Wilson, who generously took time out of their busy schedules to comb through our final drafts and share their expert advice.

Although we will continue to improve the book based on comments from you, our readers, we owe a great deal to our friends and family who proofread much earlier versions and provided valuable feedback, suggestions, and encouragement. Malcolm Gorman, Alicia Oshack, PW van der Walt, Simon Kocbek, Nelle Varoquaux, and Ariel Rokem: thank you.

And of course, we thank our editors at OâReilly, Meg Blanchette, Brian MacDonald, and Nan Barber. We are especially grateful to Meg, who first approached us about the book and who offered invaluable early guidance when we had barely a clue what we were doing.

1 Fernando Perez, ââLiterate computingâ and computational reproducibility: IPython in the age of data-driven journalismâ (blog post), April 19, 2013.

2 Douglas Adams, The Hitchhikerâs Guide to the Galaxy (London: Pan Books, 1979).

Get Elegant SciPy now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.