Chapter 4. Where’s the Rest of Me?

We all perform. It’s what we do for each other all the time, deliberately or unintentionally. It’s a way of telling about ourselves in the hope of being recognized as what we’d like to be.

—RICHARD AVEDON

THE CORE AROUND WHICH social sites revolve is people—who they are, how you know them, what they are contributing. People and their presentations of self and their contributions make for a rich and intertwined community. Without understanding who you are, your friends won’t know you. Potential connections won’t trust what you say or be encouraged to connect to you. You won’t be able to recognize your friends in the crowd of participants, and you won’t necessarily trust new people if you don’t have some way of formulating a picture of who they are.

The work that goes into defining themselves as well as building connections is often a significant hurdle for users who want to try a new site. Thus, having a well-established identity and network on one site is a considerable deterrent for switching to other sites. Help your users by automating as much as possible; aggregating activity such as comments or reviews and presenting user status streams of connections creates a rich and interesting default without requiring much work from your users.

There is a growing belief that a person’s identity belongs to him and not to the software or service in which the data has been created. The proliferation of socially enabled sites that do not interoperate means people must re-create themselves at each and every site they go to. In some cases, this isn’t an issue, because the context of the community often dictates what persona to present. But for many users, the facets of themselves that they would like to present to others just aren’t significantly different from site to site.

The success of Facebook Connect—allowing people to use a single set of authentication credentials for multiple sites and applications—has been so huge in part because of shared identity information which encompasses the rich data set that describes a person and by which other people come to know that person.

The collection of patterns in this chapter addresses the various interfaces that present personal and activity information about a person to others. They make up the components that might be considered a user’s brand: the image that he projects to others that then creates a perception of him. This includes the profile, the personalization of that profile; how a user’s contributions are attributed to him and what control is available for that; the avatar; what information is private; where a user can manage all these pieces of information; and the personal dashboard, where a person see what’s happening across his network of connections. The profile should be mixed together with attribution presentation, contact cards, and other public information to create a personal and rich people-centric experience.

The profile and the presentation of a person, whether automated through activity or customized by the individual, is how you get to know someone; it gives your users the opportunity to express whichever side of themselves they are comfortable sharing with the world.

Identity

User identity and the ability to control its presentation is a core element of building a social website. The ability to create and manage an identity within the context of the site is the foundation upon which the rest—contributions, relationships, reputations—is built. It’s about people and who they portray themselves to be.

When thinking about these topics, be aware that providing the ability for users to define their names is just step one in helping them craft their identities. As discussed in Sign-Up or Registration, allowing the user to create a nickname (rather than be saddled with some horrid identifier he got because the namespace was full) is one of the best design decisions you can make. Wouldn’t you rather be known as “jack of all design” rather than “jack089”?

There are several other items that make up an identity for the user. These include Profile, Avatars, Reflectors, and Attribution. Associated with these patterns are a user’s reputation and his connections.

When deciding what to pull together, be aware that you don’t need every piece, and that you can start with some elements and add others as needed.

Here are some points to consider across all the patterns in this chapter:

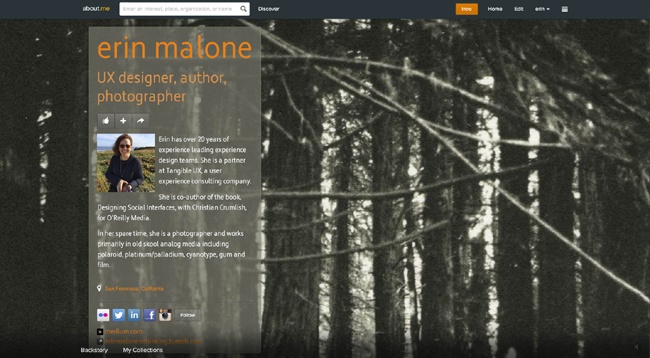

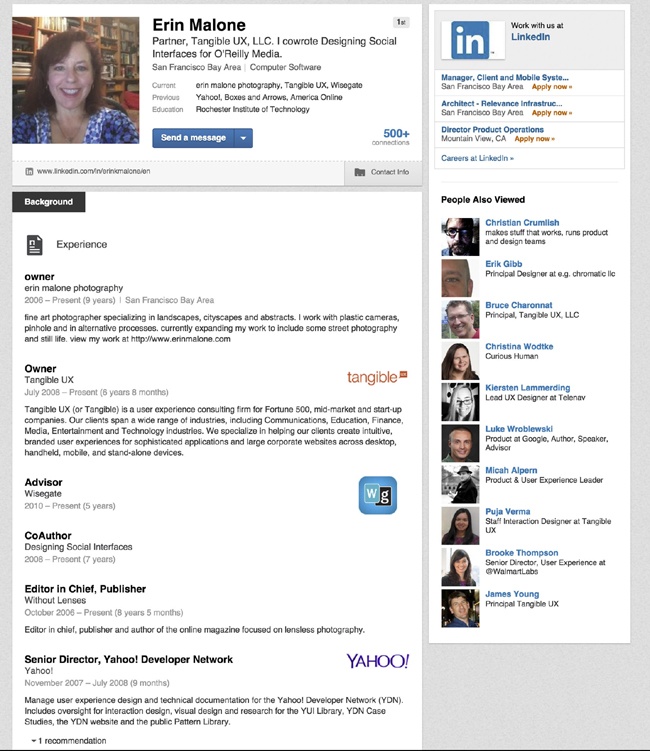

Let your users be expressive where it matters. For example, Figure 4-1 shows how profiles on About are much more expressive and reflect its more personal approach, whereas profiles on LinkedIn are barely customizable and reflect the professional nature of the interactions (Figure 4-2).

Give users control over how to present themselves. Users should own their actions and have a reputation attached to their identities, but the option to stay anonymous should be offered in some instances.

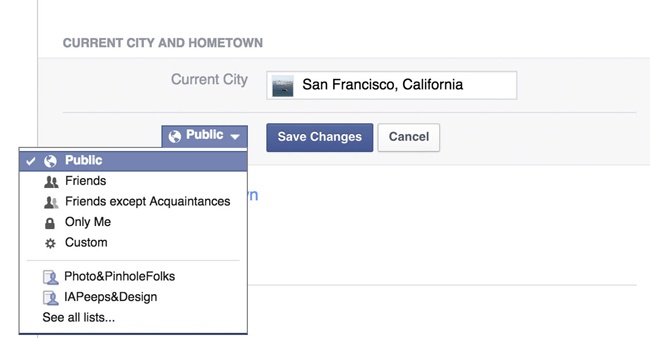

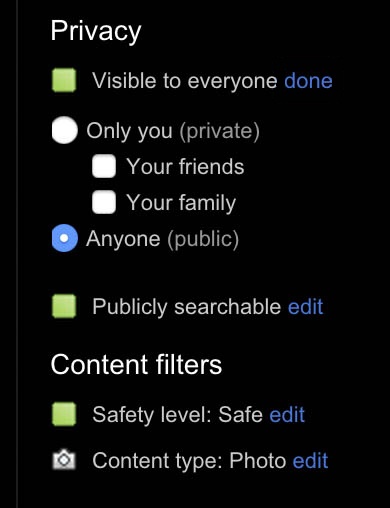

Let your users decide who sees what parts of their profiles, as demonstrated in Figure 4-3. Give enough control and permissioned access. Do my friends see my birth date, or does everyone? If it’s everyone, be prepared for a lot of fake data.

Be clear on reflecting back to users what they see as editors/owners versus how others see them. The dating sites have this idea down to a science, but on many other websites, who sees what isn’t clearly articulated.

Clearly communicate the privacy policies around the information users add as part of their profile; for example, which items will be seen or not, and which will be used anonymously in aggregation as part of the business data.

Having robust identity solutions won’t alleviate sock puppets (see Sock Puppets) and alternate identities that people might create.

Profile

The profile is one of the core pieces of a social offering. It becomes the face of the user in your system. Profiles can be an expressive place for users to create a “voice” or “image” of how they want to be seen in the context of your site. Depending on the nature of your site, they can be a hub around which relationships and activities revolve. In many services, profiles are often an aggregate representation of all the activity of a user and her friends.

What

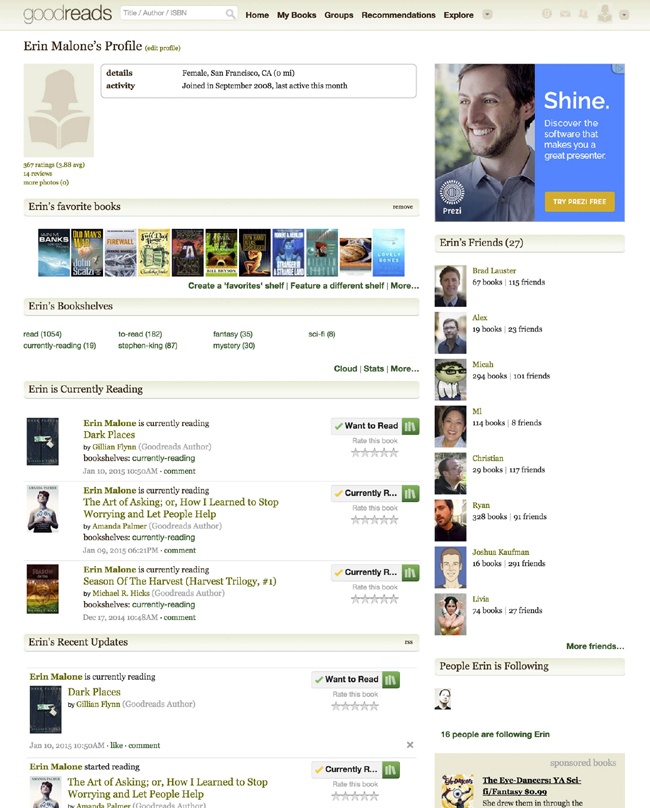

Users want a central, public location from which they can display all the relevant content and information about themselves to others—both those they know and those they don’t (Figure 4-4).

Use when

Your site/app encourages a lot of user-generated content and you want one place to show a specific user’s contribution.

Your service encourages relationship building.

You want to provide users with a means to look up another user to learn more about her.

You want to give users the ability to express their personalities.

You want users to share information about themselves with others.

You want to present a user’s activity stream (such as status alerts) from site and/or Internet activity.

How

Core profile

Provide the user with the tools to customize his display name or provide a nickname option.

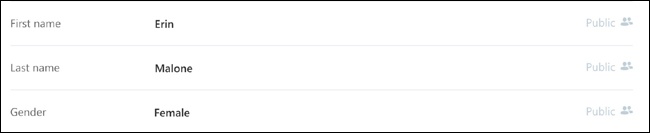

Consider collecting both a first and last name, but also accommodate a display name, which can be a handle, a nickname, or the user’s name. Let it be his choice. The full name is shared with connections, which then disambiguates who a person might be, especially if his associated image is an icon or an avatar.

Don’t make the display name the same as the user login. Doing this gives phishers and other nefarious persons half of a user’s login information. You should provide a safe place for people to connect, and guarding their login and personal information is critical.

Give users options to select which items they want seen by the public and which they want to keep private or just between “friends,” as shown in Figure 4-5.

Figure 4-5. Flickr (http://www.flickr.com) gives users the options to designate what is seen by whom when an item is uploaded.Give users the opportunity to customize portions of the profile. The profile is a form of self-expression. About profiles represent one extreme of this. LinkedIn and Facebook profiles are much more rigid in their customization, restricting it to text, an image, and the user’s activity to differentiate and define a person’s personality.

Don’t force the user to publicly display all her information.

Collect only the amount of information necessary for meaningful relationships or community activities. Don’t force the user to fill in all fields or data sections in order for the profile to be displayed.

Give the user the ability to upload one or more of her images, such as shown in Figure 4-6).

Figure 4-6. With both Google+ and Facebook, users can upload multiple images to use for the profile. The user can swap them in and out whenever she pleases quite easily (http://plus.google.com and http://www.facebook.com).Provide a view into the profile as a user’s network will see it.

Provide a view into the profile as the public—not connections—will see it.

Profile preferences and updating

Profile preferences should be readily available to the user who owns the profile. If the user is logged in, present a large, easy-to-find link to edit the profile.

One of the tough decisions to make is whether any elements of the profile are tied to the account and not editable.

The data fields selected for the profile should be individually editable, with as many elements as possible pulled in automatically (if applicable). Data for the profile is often gathered by presenting a series of questions and then filling out a series of forms and free-text fields.

Collect information for the profile data entries through site activity if possible.

Always provide a mechanism for the user to go back and change information later, but don’t force profile completion if this is unnecessary to the core site experience.

Encourage profile completion by giving users clues that indicate how complete their profiles are or by using defaults (e.g., a default avatar) that encourages customization, but don’t force completion if it isn’t necessary for a good user experience.

If possible, give the user the ability to migrate profile content, a profile image, nickname, and core personal information from other services using the OpenSocial API.

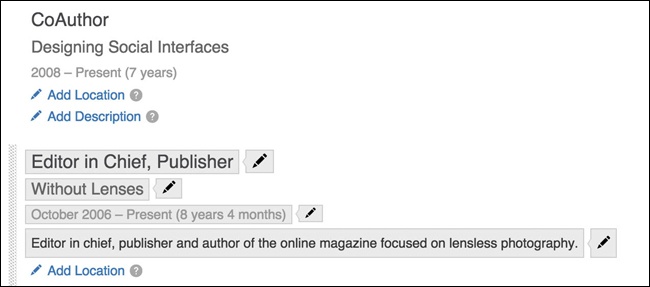

Use WYSIWYG + lightweight edit links, as depicted in Figure 4-7.

Figure 4-7. LinkedIn (http://www.linkedin.com) has light inline-edit controls, seen only by the profile owner, on each module of the profile.Wherever applicable, the profile page displayed to the user should be as close as possible to what the consumers of the profile will see. The owner of the profile should be able to get an accurate sense of what others will see without the need to preview the profile.

The differences between the consumer’s view and the owner’s view are typically limited to additional “Edit” links that point to forms for updating content.

Profiles that include a lot of permissioned content might include permissions indicators for denoting public versus permissioned versus private content. Robust profiles also might include controls for inline editing as well as drag-and-drop handles that appear on hover.

When the owner of the profile selects a link to his profile, load the profile page in Edit mode, not Preview mode.

Don’t overload the profile page with content management options for the content owner.

Do provide a separate “control panel” for the owner to manage his content.

Do provide a separate Updates/Status Consumption Environment so that the owner of the relationships can keep tabs on the content generated by related people.

Private information

Some of the information that might be collected in an account profile is private, such as a phone number or email address.

Ensure that information tied to the account, such as passwords, password retrieval questions, credit card information, and other financial and personal information, stays in a private area that is accessible to only the account holder.

Keep private information in an Account area, separated from the Profile display.

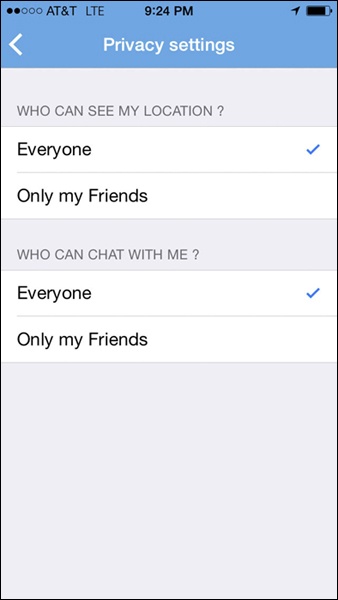

Offer the option to make private information public to only those people in the closest circles of connections, such as family or close friends (see Figure 4-8 and Figure 4-9).

Profile decorating

Many sites that revolve around the profile, such as About (Figure 4-10), encourage profile decorating as part of the profile owner’s personal expression. Self-expression is a key component of the experience and has a direct impact on the perception of the creator, as much as any other type of content she might upload. Even experiences such as LinkedIn and Twitter have included the ability to add background images to personalize and differentiate the profile, although none of them affords as much customization as the MySpace of old.

Contrast this to more task-oriented sites such as LinkedIn or Facebook, for which the content and interactions among people are considered primary, and the interface exists mainly as a means to house these. When developing a profile system, think about what is important to your users, their goals on your site, and how important the profile and self-expression might be in that context.

To encourage adoption, offer easily applied skins; that is, the ability to upload background images and custom layout options.

For more personalized profiles or for a younger audience, offer add-ons such as stickers, mini-avatars, furniture, or props for expanded expression opportunities.

Give advanced users the means to do more customization, such as CSS and HTML, but be willing to have a wide variety of quality in the system.

Provide users with a way to add different content modules or applications on an à la carte basis.

Profile claiming

Some sites might automatically create a bare-bones profile for a person and then allow that user to claim ownership of it.

An unverified or unclaimed profile may exist for a user through several methods (comment contribution, a friend’s invitation, etc.).

Users leaving anonymous comments or other anonymous content might want to eventually claim ownership of that content to build their reputations as contributors.

Users may have skeletal profiles made for them when their friends join the site and invite them to participate.

Provide a way for an invited user or owner of anonymous content to easily claim her profile or aggregated content. Dropping an encoded cookie is one way to facilitate later retrieval of anonymous content.

Verification of some data string (such as a verified email address) can pair a premade profile with the intended user.

Regardless of the technical method for allowing this, make sure it’s easy, unobtrusive, and not creepy. A few years ago, Yahoo! released a profile experiment called Mash, where users could make profiles for their friends and then invite them to come claim the profile. Many people didn’t understand why there was already content on “their” profile page and why people other than themselves could edit it. It was a fun experiment if you “got it,” but confusing and creepy for everyone else.

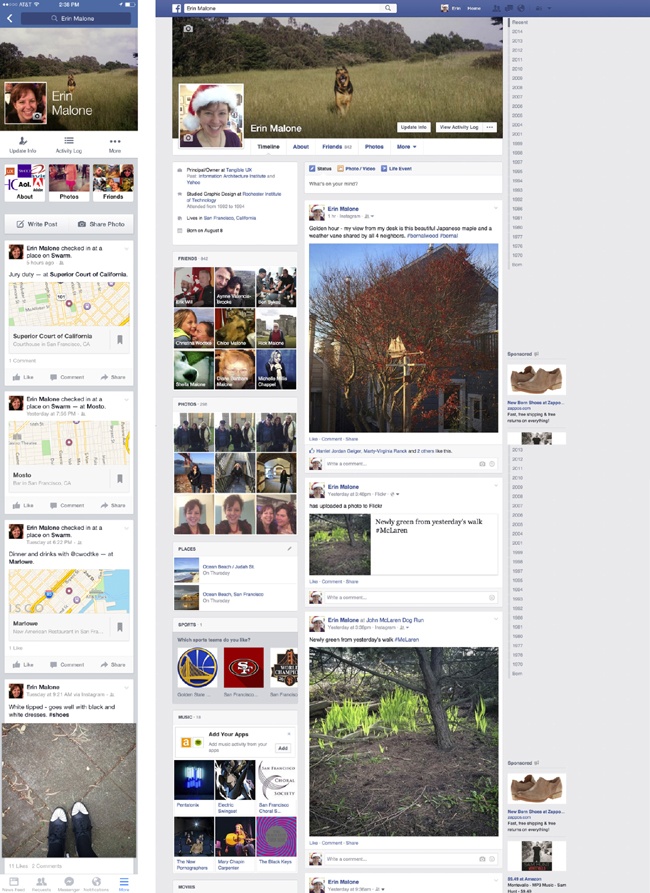

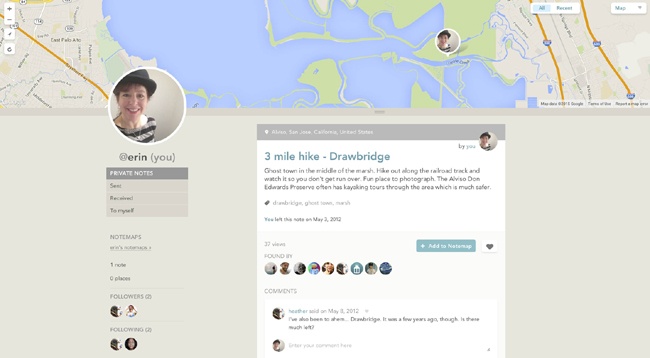

Faceted identity

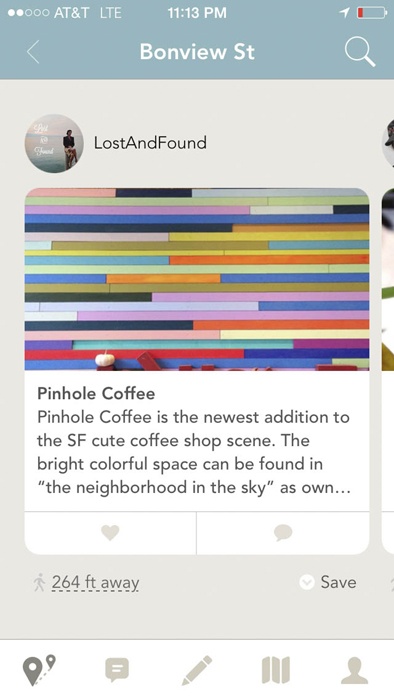

Users are quite skilled at slicing their identities up depending on the context of interaction. For example, who you are in your family is different than the slice of yourself you present at the office. Online it’s no different. See Figure 4-11, Figure 4-12, and Figure 4-13.

Consider the context of your experience and cater the profile to it.

Whenever possible, keep the core user identity information consistent—username, gender, location—through the use of a central design solution. All other information should be collected or automatically aggregated based on the activities of the site.

Recommendations

Use the emerging common profile/identity fields as defined in the OpenSocial spec (http://bit.ly/1Jo9hK6). Select the data items that are meaningful to your context and disregard the rest, but be consistent in the field labels and how the information is stored. This will ensure future portability for your users and will make it possible for you to import data from other sources when a user joins. The goal is to let the user bring her data (where applicable) with her around the Internet rather than forcing her to rebuild a profile every time she signs up for something new.

Considerations

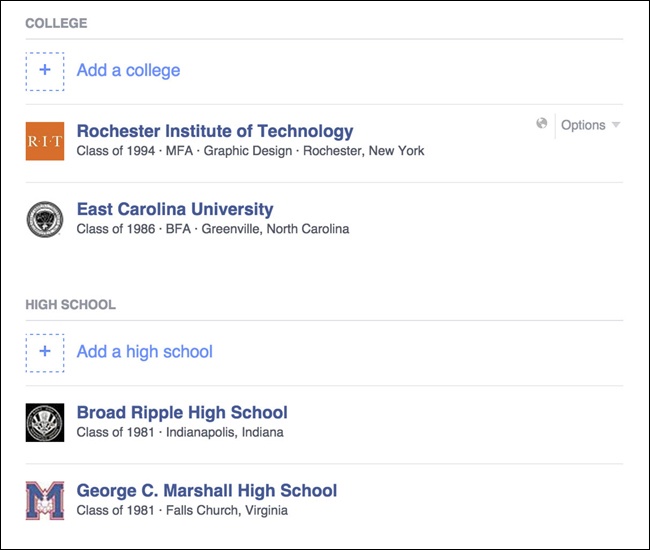

The type of information collected and presented shapes a picture of the user and sets a tone for your site. For example, LinkedIn collects professional information about current and past work experience (refer back to Figure 4-2). Profiles are supplemented by the addition of recommendations from other users and applications from third-party developers. Facebook has a series of free-form fields, but as Figure 4-14 illustrates, it also a robust section of past school attendance. Given that Facebook started as a university social network, this is appropriate. It has since expanded its profile to also include work experience and applications from third-party developers.

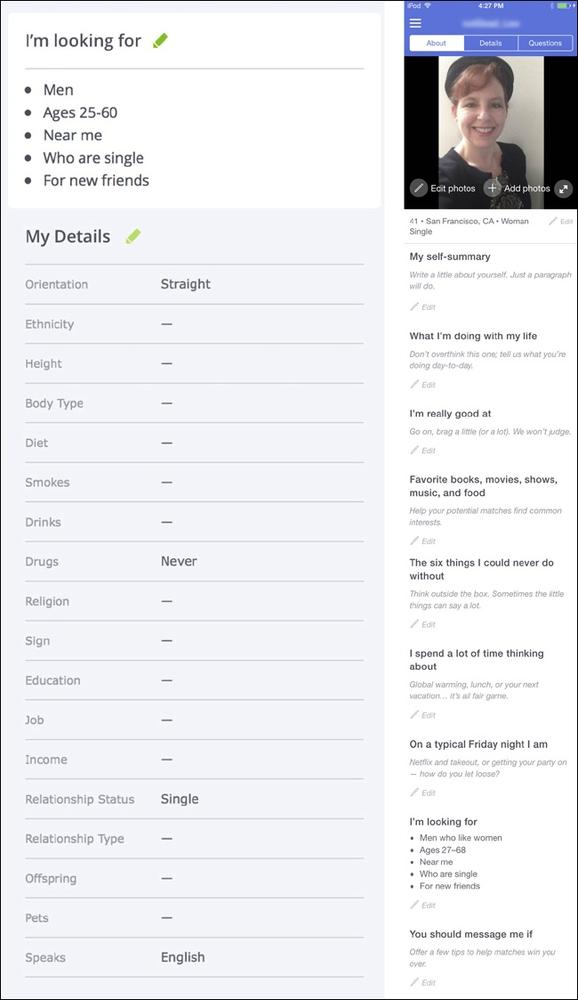

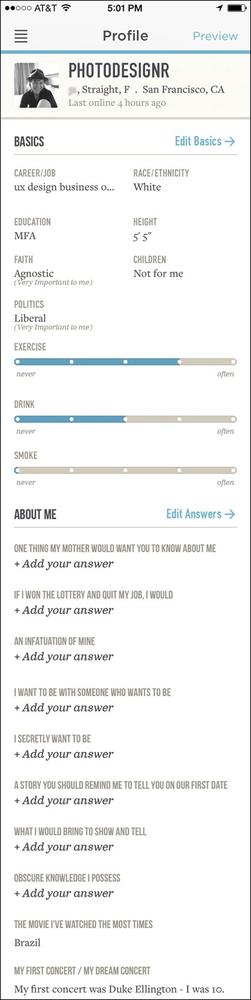

Dating profiles such as Tinder, OkCupid, HowAboutWe, and others revolve around the profile, so the information collected about the user’s marital status, the types of relationships the user is seeking, and interests such as music and video are appropriate in this context (see Figure 4-15 and Figure 4-16).

Each of these social networks uses specific profile data to give users an idea of its social emphasis and the community that exists on the site.

Open questions

As the various entities such as Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, and Google put forward open standards for the profile and a user’s identity, making a decision about which protocol to adopt becomes increasingly important. Most of the large players in the space have adopted and are participating in the OpenSocial standard. Following this standard, or being compatible with it, will make your users’ data more accessible to them in the long run.

Making a decision to go against the emerging standards might be interesting to you in the short term, but it might have negative ramifications in the long run as more and more users of services demand the ability to carry their data back and forth between sites.

Why

A central profile for your service is the hub around which relationships and other activities can revolve. Carefully selecting the data fields that make sense for your site will ensure that the profile has meaningful context to your users. Providing customizing features will encourage personalization and ownership of the profile and the site, which in turn supports longer-term usage.

As seen on

Facebook (http://www.facebook.com)

LinkedIn (http://www.linkedin.com)

OkCupid (http://www.okcupid.com and OkCupid mobile application)

HowAboutWe (http://www.howaboutwe.com and HowAboutWe mobile application)

Strava mobile application

GoodReads (http://www.goodreads.com)

Testimonials (or Personal Recommendations)

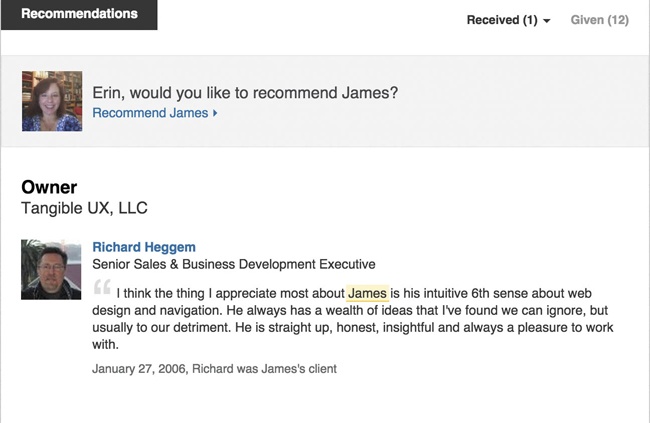

Testimonials are endorsements that can provide information about a person or about aspects of the person’s interests or skills, such as those shown in Figure 4-17. This can help round out a profile and provide alternative perspectives.

What

A person is interested in what others think about him or his work and wants others to see this as supporting his own information and skillset.

Use when

You want to provide users with means to provide endorsements for other people in their networks.

You want to share information from other people about a person in his profile.

How

Provide a module in the profile for presentation of testimonials or recommendations.

Offer the tools for people from the user’s network to write a testimonial or recommendation for the user.

Present a clear call to action when a person is viewing a profile that is not her own. Both Flickr and LinkedIn provide links to the main body of the profile in a secondary column of information.

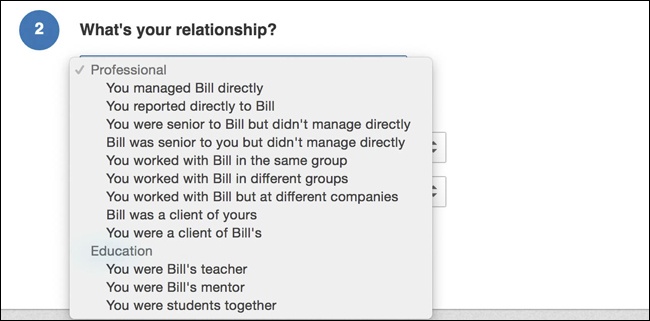

Consider allowing the testimonial writer to select how she knows this person, as illustrated in Figure 4-18.

Figure 4-18. LinkedIn (http://www.linkedin.com) asks how the writer knows the person in order to give context to the recommendation.Provide a method for the person being written about to approve the testimonial or recommendation before it is published. After all, the profile belongs to the user, and she should be in control of the content presented.

Clearly articulate to the writer that the recommendation must be approved before being published. This will deter people who want to be nasty or rude or who are trying to spam the profile.

Provide attribution for the testimonial or recommendation and link that back to the writer’s own profile. This will help lend credibility to the recommendation.

Consider presenting on the user’s profile the recommendations that she has written for others.

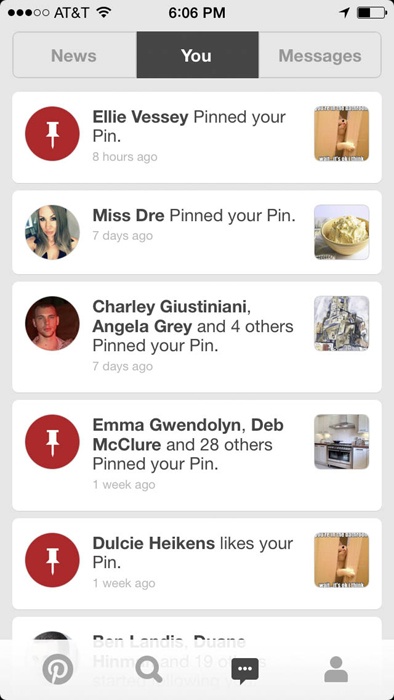

Consider presenting on the user’s dashboard (see Personal Dashboard) a block or module showing recent recommendations or testimonials written by people in the user’s network. This could also be presented in an activity stream (see Activity Streams).

Consider a light-weight alternative for users to present their perspective of others. LinkedIn offers a feature called “Endorsements,” and much like Ratings or Tagging, the investment for a user to leave feedback is low and is an easy way to encourage engagement in the service.

Why

Letting users provide an endorsement for people in their network makes it possible for them to share positive information about that person in a more permanent and meaningful way than a comment or more temporary flag of approval. For professional-leaning sites such as LinkedIn, recommendations provide profile viewers with information about the person from a variety of perspectives, which can help in making hiring or business decisions.

Personal Dashboard

What

The user wants to check in to see status updates from her friends, current activity from her network, comments from friends on recent posts, and other happenings from across her network (Figure 4-19).

Use when

The experience of the site revolves around the activities of people and their networks, regardless of whether the activity takes place on the network.

You want a companion to the public profile.

You want to encourage repeat usage.

How

Provide access to other features and applications from the personal dashboard, as demonstrated in Figure 4-20.

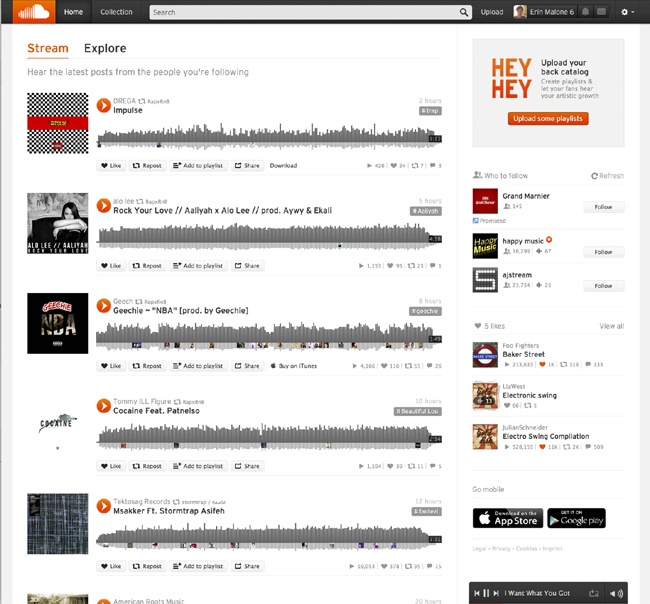

Figure 4-20. SoundCloud’s (http://www.soundcloud.com) signed-in home page shows recent posts from people I follow, makes recommendations for new people to follow, and shows the latest streams I have liked.Provide a way for users to select what elements they want displayed in their dashboards. Give them a reason to come back repeatedly.

Don’t hide important social aspects to make room for editorial or advertising.

Give users the ability to supplement their network’s onsite activity updates with RSS feeds of other activity from other sites.

Provide the ability to create a status update directly in the dashboard if status is an important part of the site.

Provide easy access to the profiles of people in the user’s network.

Provide easy access to the user’s own profile for review and editing.

Why

The Personal Dashboard is the companion to the Profile. The dashboard should contain information and access to activities that the user wants to participate in on an ongoing basis. From the dashboard, she should be able to click into her friends’ profiles to get more information about them and their interests. For sites like Facebook, Twitter, and even the activity site MeetUp, the dashboard is the user’s version of the home page for the site and revolves around recent activity of all kinds.

Related patterns

As seen on

Facebook (http://www.facebook.com)

Twitter (http://www.twitter.com and Twitter mobile application)

MeetUp (http://www.meetup.com)

SoundCloud (http://www.soundcloud.com)

Reflectors

What

A user needs to be able to edit the public identity he is participating under when viewing his profile or creating content (Figure 4-21).

Use when

A user may participate and need a persistent way to get to her public profile.

A user is about to participate and wants to change the display of her attribution.

To help clarify and confirm to a user that he is actually logged in.

How

Reflect the user’s current public identity back to him.

Present a link to view the public profile (if any) for the current context. If a contextual profile is not applicable, present a link to the user’s primary public profile.

Limit the identity information to the display name and display image. There is no need to show age, gender, location, or contextual identity information back to the owner/user. Save that data for the public view.

Editing the display name

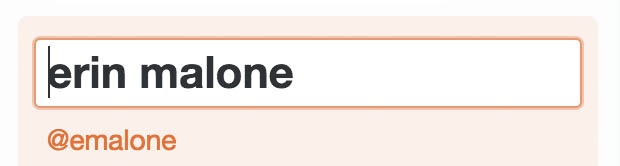

Provide an easy way to change the display of how the user will be seen (Figure 4-22).

Figure 4-22. With Twitter (http://www.twitter.com), users can change the display name on the profile whenever they want. However, it doesn’t allow changing the @ name that is associated with the account identity.To reduce identity theft and spam, encourage the use of a display name that does not expose an authentication ID or email address.

Provide the means to post in a “publicly anonymous” way to reduce the need for additional, separate identities.

In contexts that require it, provide a way for a user to post using an alternate, separate identity.

Place the control at the bottom of a content submission form so that users focus first on their contributions (not on whether they need to change their identities).

Editing the display image

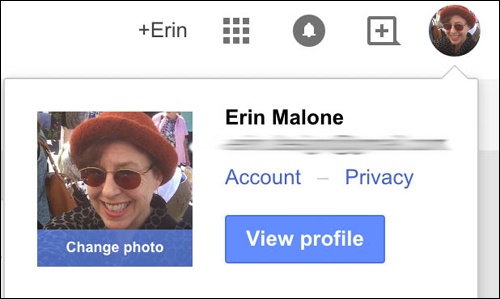

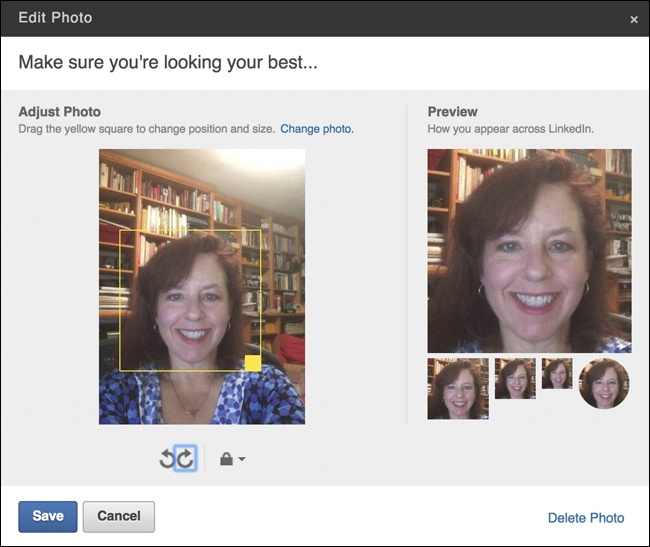

Present a link that gives the user the ability to edit and change out his display image, as depicted in Figure 4-23.

Present a window that displays the set of images belonging to the user. Use a floating window to keep the user in context.

Give the user the option to select one of his existing images (or avatar) or let him add a new image, as presented in Figure 4-24.

On sites with multiple contexts (MeetUp for example), let the user decide whether the new image should be used in all contexts or just the current context.

Why

Reflecting back the name and image with which a user is currently associated affords control over that person’s identity. There might be specific nicknames or a preferred identity in certain contexts that a person wants to use. Giving the user an opportunity to see how she will be seen gives peace of mind as well as a sense of control and ownership on the site, which in turn encourages more participation.

As seen on

LinkedIn (http://www.linkedin.com)

MeetUp (http://www.meetup.com)

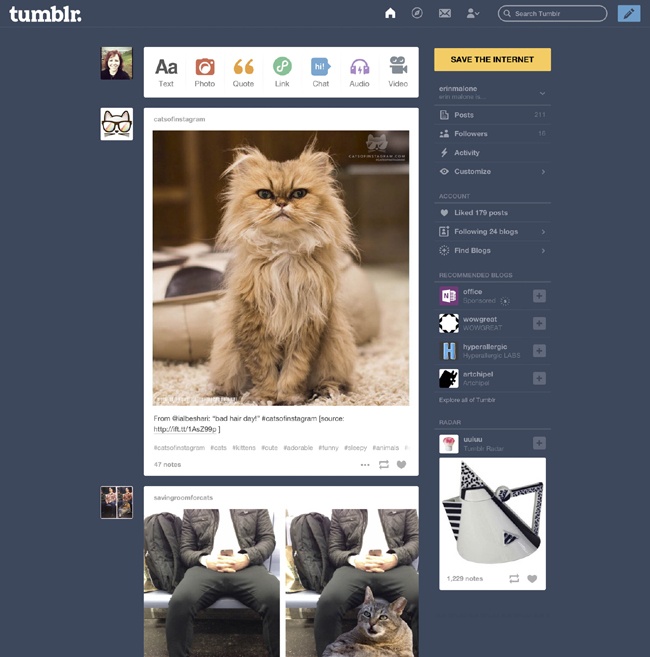

Tumblr (http://www.tumblr.com)

Identity Cards or Contact Cards

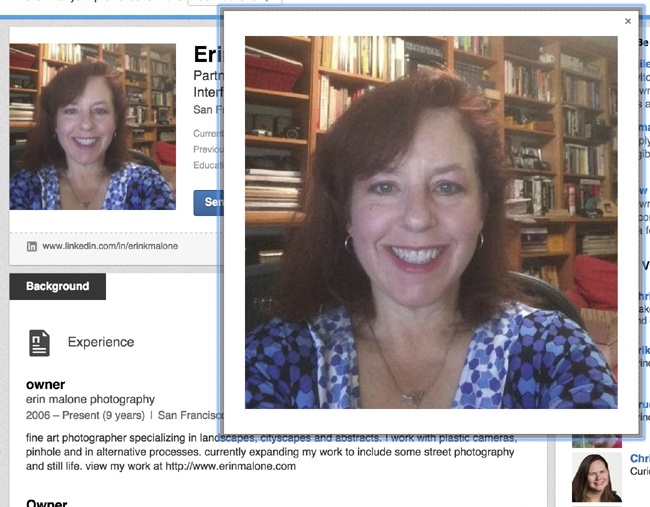

What

A user needs to get more information about another participant in an online community without interrupting his current task. The needed information might include identity information (to aid in recognition and to help the user relate to the participant) or reputation information (to help the user make decisions regarding trust). (See Figure 4-25 and Figure 4-26.)

Use when

How

Open a small panel when the user hovers over a target’s display name or image.

Present a larger version of the user’s display image, the user’s full display name, and other pertinent information that the target chooses to share with the community (real name, age, gender, location).

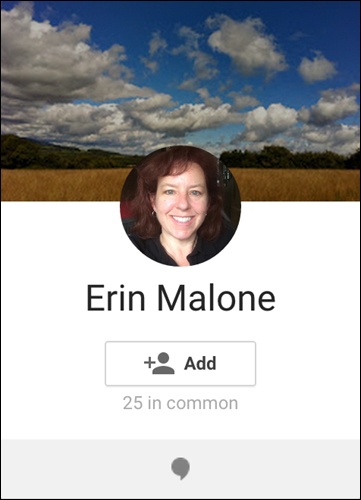

Present a Relationship Reflector, as shown in Figure 4-27 and Figure 4-28.

Provide the ability to subscribe to, follow, connect to, unsubscribe, or block the user from this panel.

Optionally extend the previously described ability with contextual identity information, such as reputation information, connections in common, or links to new participation in the current context.

Why

Identity cards or badges make it possible for the user to interact with another participant in an online community in a predictable manner and in context.

They provide the means to reduce identity-related clutter on the screen.

When ID cards are used, Presence Indicators, Reputation Emblems, and Relationship Reflectors can be tucked away but easily accessible. Truncated nicknames can be expanded. Block links can be made less salient. Small or tiny (and often illegible) display images can be shown at a more recognizable size to better humanize an online community and increase positive participation.

As Seen On

Twitter (http://www.twitter.com)

Facebook (http://www.facebook.com)

Tumblr (http://www.tumblr.com)

Google+ (https://plus.google.com)

Attribution

What

A content consumer needs to understand the source of a contribution, and the source of a contribution needs to receive proper credit for his post, as illustrated in Figure 4-29. A user needs to assign her public identity when contributing content or joining an online community.

Use when

Use this pattern when contributing content, joining a community, or editing a public profile.

How

For the content consumer

List the author’s display name and display image (if space and performance permits) in close proximity to the title (or summary) of the post, as shown in Figure 4-30.

Figure 4-30. Attribution with an avatar accompanying the headline and brief description of articles on Medium (http://medium.com).Link the display name and display image to the most contextually relevant user profile. If a contextual profile is not available, link the name and image to the user’s primary profile.

For the content creator

Reflect back the user’s current public identity and give her the ability to update it prior to submitting content or joining a community.

Why

Attribution of content helps keep people honest and owning their words and actions. The reflection back to the author, showing how he will be presented, confirms what his audience will see and the content consumer can identify people in their network, their friends, or experts and associate that with a level of credibility and expertise associated to that specific user.

As seen on

Tumblr (http://www.tumblr.com)

Reddit (http://www.reddit.com)

Yelp (http://www.yelp.com)

Pinterest (http://www.pinterest.com)

Medium (http://www.medium.com)

Avatars

Avatar is both a generic name for a visual representation of a user online and a product name for animated/cartoon or 3D renderings and drawings that represent a user online. In the December 2, 2008 issue of the New York Observer, Gillian Reagan writes:

Profile pictures—or avatars, in online parlance—show people at our thinnest, handsomest, most fun (some call these our best “MySpace angles”). But increasingly—as more than half the country use social media regularly, according to marketing research firm IDC—the entertainment value of these sites is segueing into something more serious; social networks can help snag a job interview, a date or even the No. 1 spot in the Oval Office. And as the sites get more important in our professional lives, so does the avatar. It’s the image that sums up who we are online.

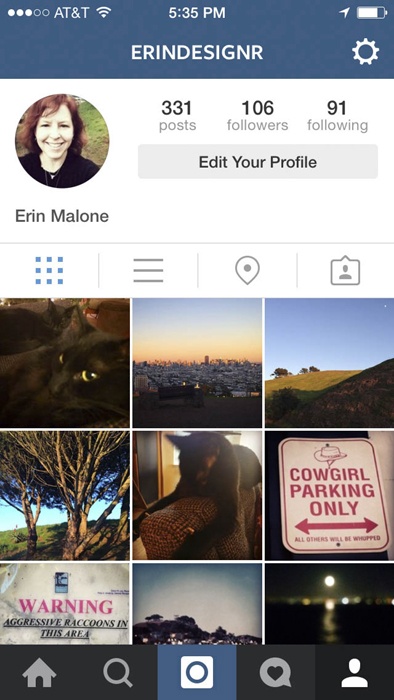

What

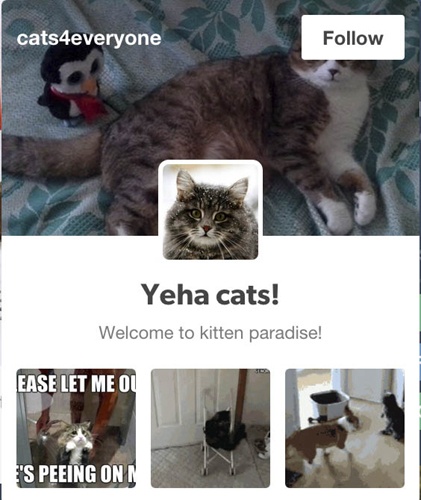

A user wants to have a visual representation of herself as part of her online identity, as is demonstrated in Figure 4-31.

Use when

Use this pattern when the user wants to have a visual associated with her identity.

How

Provide a mechanism for the user to upload any kind of image as an avatar. This can be a small portrait, an icon, or an illustration that the user believes is representative.

Provide an option to upload a larger image—400×400 pixels—and automatically resize for smaller uses. Many services use an image that is 60×60 pixels inline, but a larger image—100×100 pixels or 400×400 pixels—can be used on the profile (see Figure 4-32). Resize the image for use in contact lists and mobile screens. These are often much smaller than what is used on the Web.

Avatars (the illustrated representations) allow for a degree of anonymity (Figure 4-33), but do reduce the perceived credibility of the poster in many cases.

Default image

If the user has not designated a display image for the current context, use a “Not Pictured” image as the default avatar, such as is shown in Figure 4-34. This encourages the user to customize so that he has an identity that is unique from other users.

Multiple avatars

Give the user the ability to upload multiple avatars and to change the presentation through the edit capabilities on the profile or identity card in context of use. (See Editing the display image in Reflectors in Reflectors.)

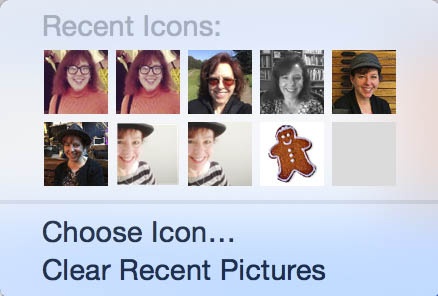

Google+, Facebook, MeetUp, and other services’ identity cards and reflectors make it possible for users to upload multiple images. The instant messenger software Adium lets the user select the current image from up to 10 recent icons, as depicted in Figure 4-35. In other cases, when users want to change their avatars, they upload another image and overwrite the previous one.

Consider giving the user the ability to upload and store multiple images for later selection.

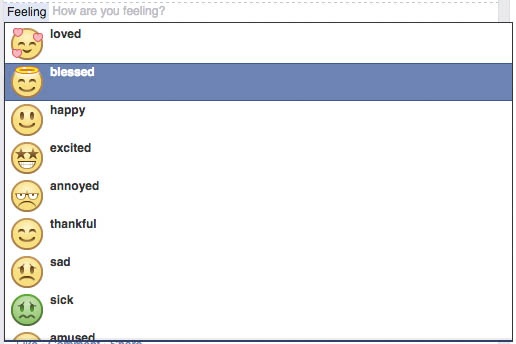

Mood expressions

Include a way for users to attach a special status message or emoticon to supplement their avatars by indicating a particular mood (Figure 4-36).

Consider when to use mood expressions versus a status message associated with the profile image.

Why

By providing a method for users to upload images, you encourage them to build up real identities. The avatar or image gives users a way to associate a likeness and a reputation with the person.

As seen on

Google+ (http://plus.google.com)

Facebook (http://www.facebook.com)

Instagram mobile application

Adium application

Portable Identity

Since as far back as 2001, there has been talk about developing a global and portable identity, and the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) developed some principles toward defining that effort. Over the past several years, this has been slow in coming about due to conflicting business concerns, a fractured marketplace, and the open movement focused on other initiatives. Thus, in the vacuum of a true viable central solution, the idea has succumbed to the ease of using Facebook Connect or Twitter’s auth solution.

The W3C working group has published a set of specifications laying the groundwork of a truly portable identity system as owned by users rather than having identity data locked into a single company. You can view these specifications at http://bit.ly/1SNhwQD.

At this point, though, people still must decide which service to sign up with and which data to move or enter contextually, and the number of services and systems hosting pieces of a single person’s identity is dizzying. Ultimately, people will use whatever seems easiest, even if it isn’t the safest or isn’t the most agnostic in terms of the business providing the service, all in exchange for speed in populating their data and jumpstarting their experience.

Further Reading

Grohol, John M. “Anonymity and Online Community: Identity Matters.” http://www.alistapart.com/articles/identitymatters.

Wenger, Etienne. Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity. Cambridge University Press, 1999.

boyd, danah. (MS thesis) “Faceted Id/entity: Managing representation in a digital world.” http://smg.media.mit.edu/papers/danah/danahThesis.pdf.

Lardinois, Frederic. “Facebook Continues to Dominate Social Logins.” January 27, 2015. http://tcrn.ch/1Joc9qi.

Donath, Judith S. “Identity and Deception in the Virtual Community.” http://bit.ly/1Joc9Xv.

Schneider, Tim and Michael Zimmer. “Identity and Identification in a Networked World.” http://bit.ly/1JoccTd.

Internet Protocol Identity Community Group, https://www.w3.org/community/ipid/.

Hinchman, Lewis P. Memory, Identity, Community: The Idea of Narrative in the Human Sciences. (SUNY Series in the Philosophy of the Social Sciences). State University of New York Press, 1997.

“No More Put A Skirt On It.” http://bit.ly/1DHpVOz.

Gergen, Kenneth. The Saturated Self: Dilemmas of Identity in Contemporary Life. Basic Books, 2000.

Mishler, Elliot G. Storylines: Craftartists’ Narratives of Identity. Harvard University Press, 2004.

Reagan, Gillian. “Superstar Avatars.” http://bit.ly/1DHq0Si.

Wagner, Kurt. “Users Log in with Facebook Instead of Creating New Accounts Online.” October 29, 2013. http://on.mash.to/1JocpWh.

The W3C Open Social Web Working Group, http://bit.ly/1Jo9hK6.

WebID Community Group, https://www.w3.org/community/webid/.

Get Designing Social Interfaces, 2nd Edition now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.