Preface

Products Are for Customers

PRODUCT DESIGN IS NOT JUST ABOUT shipping.

It’s not just about being original.

It’s not just about making things beautiful or stylish.

And it’s not just about making something easy to use.

Product design is about creating something that’s right for your customer by completely understanding what they feel, what they think, and what they want.

But, ultimately, designing a product means designing something that sells.

Because that’s why a product exists in the first place.

This isn’t a new notion. “The purpose of the enterprise is to create a customer,” wrote legendary organizational expert Peter Drucker in The Practice of Management.[1] And he wrote that almost 50 years ago.

Maybe you’re reading this book because you or your team have been stuck in the ship-pivot-ship loop of death, and can’t figure out how to get out of it.

Perhaps you’re reading this book because your team wants more “design-minded solutions,” and you’re in an ancillary design role.

Or you might’ve been intrigued by the money. It’s hard not to be. The number of designer-led companies that have raised money or have been acquired in the past few years is only rising.[2]

Whether it’s for survival, adaptation, or vanity—or none of the above—I’m glad you’re here.

You’re going to learn how to ignore all of the noise.

You’re going to learn how to create products that sell.

Creating a successful digital product is the ultimate realization of creativity, hard work, and leadership. We too easily forget that products are made by people, for people.

The result is that the how of building a product has become mystified, detached from the what of a product.

That’s because the way that successful products are built is a competitive advantage for all companies, from the largest—like Facebook and LinkedIn—to the smallest up-and-coming startups you haven’t even heard of yet.

Overnight successes are rare. Successful products aren’t happy accidents, as we’re led to believe. And most of them are too often made sloppily and without good practices.

So how do you create a product that sells?

I’ll promise you that it doesn’t begin with devouring biographies of mythologized figures, repeating the phrase “if you build it, they will come,” or thinking that if we just get it out there, we’ll know what to build next.

Let’s talk about why this is the book for you.

Why This Book Is for You

The dopamine rush is as clear as yesterday.

I was a founding team member of a Kleiner Perkins–backed online video startup, leading product.

And we were adding one million users a day.

These stats seemed to validate that people loved the product I helped to create.

But the party didn’t last. We rode a wave of hope to over 20 million registrations until traffic died, interest waned, and the product was shut down in November 2013.

I wondered why it happened. How over 20 million people were convinced to sign up for something they didn’t want. And what led us to believe that this was real success.

The experience left me hungry to know how the best products are made. It led me to examine how product designers work, how they create products people want, crave, can’t live without—and how they do it over and over again.

One might chalk up this anecdote to not achieving the exalted “product/market fit,” after which one might encourage me to “fail faster” by “pivoting” into a new idea. After that, we’d then turn around and “validate” the idea and tweak accordingly.

But this process also led me to wonder—what if this framework was flawed? What if we didn’t have to launch products with prayer and carefully planned viral loops, only to keep praying as we dove into the next pivot?

This Book Is For You

This book is written for anyone who wants to be better at creating digital products. Because when we learn to improve the how of doing things, everybody benefits when we put it into practice.

My goal is to show you how to create successful digital products, regardless of the industry in which you operate. I’ve interviewed more than 30 product leaders, studied the history of how products came to be made, and pulled out the repeatable processes and strategies they used to win.

You’ll find my interviews with these experienced product designers at the end of each chapter. All, however, have been truncated for brevity. You’ll be able to read all interviews in their entirety at http://scotthurff.com/dppl/interviews.

In these Q&A sessions, you’ll learn about how these accomplished product designers work. How they grind through creative dry spells. Where they seek inspiration, and how they work through product challenges with their teams. And better yet, you’ll learn the repeatable processes they use to churn out products that people use again and again.

At the end, you’ll see how products like Medium, Twitter, and Squarespace—along with many others—are created and improved. Their workflows and processes are here for you to dissect, and to apply immediately.

We’ll see how they come up with early gems of product ideas, the methods they use to gut-check those gems, and how this research affects the actual product design.

Then, we’ll step into their heads as they design, prototype, iterate, and test the actual product. We’ll hear about how they gather customer feedback and use it to stack the odds in their favor when they finally launch.

That being said, the techniques in this book are useful for anyone, whether you’re a solo entrepreneur, startup worker, or a member of a larger organization experiencing any of the following challenges:

Products built with a head-in-the-clouds mentality that results in a launch that finds no customers.

Projects that are plagued by last-minute changes, not-fully-considered flows, or technology that can’t deliver on the product’s promise.

Customers who are confused about how to use a product that was just launched, despite it seeming “obvious” to the team.

Fear that you’re falling behind, not learning fast enough, and not offering enough creative ideas.

An ability to recognize “good design,” but a tendency to get caught up in the details, second-guessing design decisions and forgetting the entire purpose of the product: putting the customer first, not second to the user interface convention of the moment.

When you’re finished with this book, my goal is for you to take away the following:

Understand how the products you use on a daily basis came to life. Jump inside the minds of highly effective product designers in top companies to learn how great products get made. Apply these workflows immediately to your own.

Learn simpler ways of discovering and interpreting customer pain or joy, and how you can use this as a vision to guide your team through the messy product creation process.

Take away the pain of designing interfaces across different form factors—mobile, desktop, tablet, web, TV, cars—by learning about user flow, epicenter design, state awareness, and primary actions.

Discover the latest psychological research being used by product designers to create habit-forming and emotionally engaging experiences.

I’m not going to pretend that everything in this book is novel, original, or has never been done before. That’s, in fact, the point. The reason this book exists is because I wanted to find product designers actually doing the work. They’re the ones who’ve taken the various popular models and methods and actually turned them into something real. Here, you’ll read about how the real work is done.

What’s in the Book

Creating a new product is like taking a photo.

The picture you want to capture is right in front of you, but you’re not sure which zoom setting will bring your subject’s crisp lines, sharp angles, and stark detail into the frame. So you turn the lens back and forth, gradually settling on the zoom that’s right for the lens and for the photo.

Of course, the subject in front of you could be moving—smiles and facial expressions, leaves blowing in the wind, wildlife running out of frame. So you do your best to capture the best possible story in one frame, adapting to the realities on the ground.

Building a product has similar challenges. This is a process that starts out with a clear goal and stated target, but will probably be forced to adapt its angle and scope along the way. Even so, you try to find the best possible solution to meet your goals and satisfy a customer.

But we’re not the first ones to face the challenges of creating products for other human beings. That’s why we’re going to examine the past so we can design the future.

The product creation model

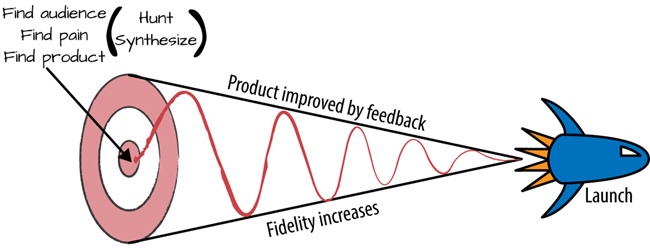

The process of creating a product is messy. But I’ve tried to break this complex creation process down into four basic steps. These steps provide the framework for the chapters in this book (Figure P-1):

Hunt and synthesize

Build

Test and level up

Launch, monitor, and start over

You’ll be seeing this a lot throughout the book, so let’s explore what it means for a second.

Hunt and synthesize

Products begin and end with the pain and joy of your customers. Coming up with product ideas that’ll work is really the search for these two traits in your target audience. Doing the hard, laborious, unforgiving work of searching for pain and joy among your target audience guarantees you’ll discover a need that is being underfulfilled or overlooked by your competitors.

In Chapter 1, you’ll trace the origins of modern digital product design to the 20th century’s earliest pioneers of product creation: Lillian Gilbreth, Henry Dreyfuss, and Neil McElroy. Each conducted painstaking, extensive customer research in the field and used it to shape the products they made.

In Chapter 2, you’ll learn why the act of uncovering people’s pain is at the source of product success. You’ll discover how to analyze customers in their natural habitats, and learn about the Pain Matrix, which helps you understand how different types of products create a variety of emotional responses in their customers.

The next step is to take this research and to make it consumable by your team. You’ll need to convince them of the right path, so in Chapter 3, you’ll discover how to rally people around your cause while deciding what product to build. Who’s in the room together? How much do they know about the pains you’ve found? What evidence should you bring to the table? And how do you frame the discussion? Here, you’ll learn how to home in on the customer’s need as a foundation, and guide the process by which a product is built upon this foundation. You’ll see how the findings of your customer research should be vetted with your team, learn meeting techniques that get results, and discover how to keep people on task and engaged after the first meeting is over.

Build

Don’t design the logo first. Don’t design the marketing site first. Design the product’s interface first.

Designing the product’s interface starts with actually writing the interface, creating and analyzing user flows, building prototypes to externalize your ideas, and evolving the interface on top of the prototype. As you approach product launch, this phase will bring your product more into focus as fidelity increases from testing feedback.

Mapping out every screen with the prewritten copy helps identify the major problems of user flows early on. It also requires you to think ahead about what types of data are required and when, forcing you to build data collection steps into these flows. This is what we’ll examine in Chapter 4, where we’ll also explore the various techniques product designers use for creating user flows. Sketching? Wireframing? How do you express each possible state? The takeaway is that there’s no one perfect way to do this. The goal is, as a famous stormtrooper once said, to “move along now,” and get something working as quickly as possible without having to juggle all of the product’s variables in your head. Clarity and communication are paramount.

Product design thrives on the power of prototyping and externalizing the ideas in your head to visuals for your team, clients, and potential customers. You’ll learn about this in Chapter 5. The importance of this early lower-fidelity work increases as we enter this next phase of the design process. Your earlier investment in this foundation serves as a guide for what you’ll be doing next. Once the copywriting has been roughed out and the user flows mapped, the goal in this phase should be to get something working as quickly as possible—working being the operative word.

Chapter 6 examines the mechanics of interface design. You’ll learn about the five base states of every product’s screen and how to design for them, while incorporating essential user interface principles. Here, you’ll also come to understand the delicate transition that occurs when moving from a rough prototype and into more high-fidelity screens. Next, you’ll see what it takes to design across different form factors—mobile, web, desktop, TV, watch—and how to optimize for human hands.

But simulated prototypes and static mock-ups aren’t the only things that make up a user interface and create memorable product experiences. Chapter 7 will help you tap into the psychology of the experience. We’re all human and we’re not immune to emotion. How can products tap into that emotion? How can emotion be used to create powerful feedback loops that draw your customers into the experience, and keep them coming back for more?

You’ll also learn why transitions, animations, personality, and positive reinforcement are essential to the psychological impact of your product. And you’ll see the power of infusing your product with personality and the various ways that this personality can shine through (copywriting, characters, art, inside jokes). You’ll also learn how to design transitions and animations that match the personality of your product. Finally, you’ll see why it’s essential to examine your product’s flows to create powerful feedback and engagement loops. Beyond alleviating your customer’s pain, how do you make people want to use your product? What psychological underpinnings should you keep in mind?

Test and level up

Creating a product is a long road of refinement before each release. And refinement comes from real feedback and critiques of prototypes of various levels of fidelity—from your team, friends, family, outside beta testers, or even customers. You’ll learn in Chapter 8 how to take this feedback—good and bad—in the gut and soldier on. This is where we examine the practical aspects of gathering this feedback and how to interpret it. You’ll also learn the early warning signs that you’re building the wrong product, and understand the role of feedback in “leveling up” your product.

Launch, monitor, and start over

How do you know when to ship? How do you prepare for launch? Chapter 9 shows you why it’s essential now that you take special care of every aspect of your product at this stage. You’re the “COE” (chief of everything) of your product. You need to know how it works, what stage it’s in, what issues are open, and what’s next at all times. And your responsibility doesn’t end once the product has shipped.

Here you’ll see how to combat the cult of “minimum viable product” and how quickly you’ve built something versus the quality and efficiency of the product. We’ll contrast this with the notion of “minimum lovable products”—the point where a product is capable of being accepted by your customers either as a problem solver or bringer of joy—but with the understanding that it’s not without flaws.

Finally, you’ll learn what things to monitor after launch, and how to stay both sane and creative in the trough of despair.

I can’t give you a recipe for how to make a successful product or satisfy a customer, because building a product depends on a multitude of factors—the market you’re in, the people with whom you work, and the inherent biases you or your team might have.

What we can do together, though, is explore examples of successful work being done, while providing both frameworks and principles you can bring into your own work life.

Rather than be a simple series of do’s and don’ts, I want to take you on a journey through the creation of a product through the eyes of experienced product designers.

How to Use This Book

A short note before we begin: at the end of each chapter, you’ll find three items.

First, I’ll recap what you just read in bite-sized bits. Copying and pasting these into a document, writing them down in a Moleskine, or posting them on your social network of choice will help you to remember what you just read and help you return to your favorite passages at a future date.

Second, the Do This Now sections will help you to implement what you read into your own process.

Third, each chapter concludes with a transcript of interviews I conducted with experienced product designers (you’re reading a preface, so they’ll start with the next chapter). Each interview fits within the theme of the chapter. My hope is that you’ll be able to understand the background, motivations, and techniques of the individual product designers who’ve helped form the thinking behind this book.

So, what’s next?

We’ll examine why successful products start with observing what real people do—not what you think they do. We’ll then explore time-tested techniques for figuring out what your potential customers really want.

Let’s begin.

Shareable Notes

How products get made is a competitive advantage for all companies.

Most products, both successful and unsuccessful, are too often made sloppily and without good practices. The biggest offender? Believing that technology is special, and that we can ignore time-tested product-building practices simply because distribution and creation are cheaper.

The proliferation of connectivity, mobile devices, and cheap technology is making design more valuable than ever.

The product creation process has four phases: hunt and synthesize; build; test and level up; launch, monitor, and start over.

Do This Now

Read the next chapter!

Get Designing Products People Love now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.