Chapter 4. Bones

If your body were nothing more than a loose package of skin, muscle, and fat, you wouldn’t be much to look at. Fortunately, your body includes a sturdy substructure—your bones—that shapes you into the fine-looking specimen you are today.

You probably think you understand your bones pretty well. They support your body, protect your tender organs, and provide a handsome frame on which to drape some designer duds. But like the rest of your body, your bones are doing a lot more than you may realize. For one thing, your bones are a work in progress—and they stay that way for your entire life. That’s because bones are built out of living tissue that continuously refashions itself. Your body constantly creates small holes in your bones, then patches them up—this keeps your bones healthy and strong. And, like your muscles, you strengthen your bones by straining them in just the right way.

If you think these facts don’t add up to much more than fodder for a late-night biology bash, think again: Understanding these processes gives you the essential insight you need to care for your body.

In this chapter, you’ll see how this knowledge can help you sustain sturdy bones, avoid joint pain, and keep your back on track. In fact, your newfound awareness just might make the difference between a body that glides gracefully into old age and one that limps into the hospital for double hip-replacement surgery.

The Skeletal System

Skeletons bring strange images to our minds. We associate them with long-dead bodies, Halloween parties, and pirate flags, which is why it seems odd to imagine a skeleton engaged in ordinary, day-to-day activity. Consider, for instance, this decidedly relaxed skeleton, drawn as a study in anatomy by Mecco Leone in the 19th century:

We don’t know what this skeleton is doing—perhaps it’s cleaning its foot, scratching an itch, or searching for a wart (which it certainly won’t find). Whatever the case, the picture is a vivid reminder that skeletons aren’t simply symbols of death and decay. They’re a fundamental component of the human body—one that lurks just beneath our more familiar layers of skin, fat, and muscle.

Note

Your skeleton has a set of 206 neatly interlocking bones. Infants, however, have many more bones—in fact, they start with an impressive 350 bones at birth. As they grow, their bodies replace soft cartilage with new bone matter, and some bones fuse together. For example, a child’s skull begins as six separate bones that gradually fuse and harden.

The Benefits of Bones

The purpose of your skeleton seems simple enough. After all, if you didn’t have one, you’d be as saggy as a beanbag chair and a lot less fun. But as you’ll discover, your skeleton isn’t just a handy place to hang your body. It’s actually a hard-working team member that helps you out in several ways:

Protection. Your bones provide rigid pieces of body armor that protect your critical squishy parts. The best examples of this defense are your skull (which wraps your brain in a non-removable helmet), your spinal column (which sheaths the central highway of your nervous system), and your breastbone and rib cage (which deflect damage away from internal organs like your heart and lungs).

Movement. As you saw in Chapter 3, your muscles are your body’s real movers and shakers. But muscles need to act on something to produce movement, and that “something” is your bones. Your muscles pull them like the levers of an intricate machine.

Storage. Your bones are a reservoir of minerals like calcium, which your nervous system and muscles need to function. For example, if your blood doesn’t have a bare minimum of calcium, calcium will gradually leech out of your bones and into your blood. (This happens during the ongoing process of bone repair, which you’ll learn about on Bone Health.) Some bones also store a last-ditch deposit of fat, which they keep in their hollow core.

Production. As you’ll see in the next section, bones don’t just lie there lifelessly. They house a busy factory that creates blood cells.

Note

Blood cells are tiny cells that circulate in your bloodstream. They play several essential roles. Red blood cells carry life-sustaining oxygen throughout your body (The Great Gas Exchange). White blood cells produce antibodies that battle infection (The Second Front: Inflammation). Platelets create clots that prevent your blood from leaking out of damaged skin. Without any one of these players, you’d be in serious trouble.

Men and women have subtly different skeletons. On average, women have narrower shoulders, shorter arms, and wider hips than men, so women are less suited to actions like throwing and running, but have better stability and a lower center of gravity. There are also a number of subtle differences between male and female skulls. Women’s skulls, for example, tend to be less angular, and they have a less pronounced, softer chin. In a random face-recognition test, most people can quickly separate the women from the men.

Living Bone

If you’re like most people, you think about bones as the dry, stiff specimens you see holding up dinosaur heads in museums or keeping turkey legs together on Thanksgiving. But the bones in your body are a world away from these fossilized and cooked leftovers. They’re still tough and impressively resilient, but they’re built of healthy, living tissue, just like all the other parts of your body. That’s why children can grow taller month after month, and why your body can restore a cracked bone to its original strength. On the darker side of things, that’s also why bones are susceptible to cancer.

You might assume that bones bother changing themselves only at certain times in your life—for example, as you grow through childhood or recover from an injury. But even if you’re an adult with pristine bones, your body is constantly busy breaking them down and rebuilding them in a process called remodeling (which, happily, doesn’t involve unreliable contractors or flighty home decorators).

To perform this ongoing regeneration, your body dissolves small patches of bone one bit at a time, and then fills the resulting holes with new material (sort of like an industrious road-repair crew). Remodeling serves three purposes. First, it fixes microscopic cracks in your bones. Second, it rebalances the strength of your bones, toughening up the parts that you strain most often. And third, it manages your body’s level of important minerals, like calcium.

For example, if you have extra calcium circulating in your blood, your body incorporates it into newly laid-down bone. But if your body is short of calcium, it reclaims the mineral from the chewed-out bone matter as it remodels, and contributes less calcium to the newly patched-up bit. This presents a problem, because without those hard minerals, your bones won’t have their full and proper strength. That’s why a low-calcium diet puts you at increased risk of developing fragile bones.

Remodeling is slow work—in fact, it takes months to fill a single hole. However, you have roughly a million independent repair crews working throughout your body, and together they do enough work to give you a new skeleton every decade of your life.

Bone Health

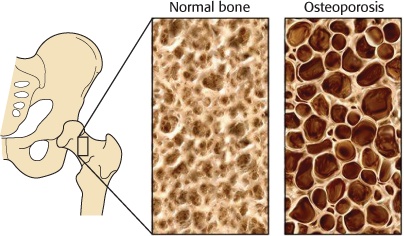

Remodeling presents another potential problem. When your body restructures your bones, it uses one set of cells to break down bone matter and another to rebuild it. If the wrecking crew starts working more quickly than the repair crew (which, after all, has the more difficult job), the whole process weakens your bones. Left unchecked, this leads to brittle bones and a dangerous condition known as osteoporosis.

Osteoporosis is a dismayingly common condition in the over-50 crowd. It’s particularly common in women after menopause, because the change in hormones affects the body’s rate of bone construction. Osteoporosis usually develops without symptoms until your bones are severely weakened, at which point you can fracture them from seemingly benign events, like a negligible fall, a minor bump, or even an ordinary strain like coughing.

Osteoporosis has the potential to greatly reduce the quality of life in your later years. However, it’s highly preventable if you follow the right steps throughout your life. Here are the cornerstones of good bone health:

Exercise. Like the rest of your body, your bones need to be used. In fact, they grow denser and stronger in the areas you stress most. Weight-bearing exercise is best for bone health (see How to Lift Weights), but even aerobic exercise (running, jumping, hip-hop dancing) helps, because these activities strain your bones with a force equal to several times your weight.

Calcium. It’s a critical nutrient early in life, when your bones are growing. It’s also essential later in life to ensure that your body doesn’t open up your bone checking account and make a calcium withdrawal. Adults from the ages of 19 to 50 should strive for at least 1,000 milligrams of calcium per day. At the same time, make sure you’re getting enough vitamin D (Vitamin D), because it aids in calcium absorption.

Note

The easiest way to get your calcium is from skim milk, which supplies about 300 milligrams per glass. Other calcium-rich foods include cheese, yogurt, and fortified cereal. Some vegetables, nuts, legumes, and fruits provide smaller amounts of calcium—usually closer to 100 milligrams per serving. (You can read a detailed calcium food ranking at http://tinyurl.com/blnwya Avoid mixing calcium-rich foods with caffeine, because it impedes calcium absorption. Finally, if you don’t think you can consistentlyget the calcium you need from your diet, or you’reat particular risk for osteoporosis, see your doctor for advice on taking a calcium supplement.

Smoking. Avoid it. (No surprise there.)

Testing. If you’re concerned about the health of your bones, you can take a simple, safe test that scans your body with a low-dose x-ray. The results will tell you if you’re suffering from the early stages of osteoporosis. In addition, the test will give you a benchmark against which you can compare future results to see how your bones change over time.

The Blood Factory

Learning that your bones are made of living tissue may surprise you, but your bones have even more going on. This time, however, the party’s on the inside.

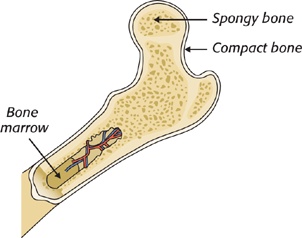

To understand what takes place, you need to realize that bones aren’t solid all the way through. Instead, your bones have a hard outer layer and a honeycombed inner layer that’s laced with tiny holes. This combination gives bones an interesting characteristic—they’re both impressively strong and surprisingly light. In fact, for their weight, bones are one of the strongest materials on earth.

Furthermore, many bones have a hollow cavity packed with jelly-like bone marrow. Bone marrow comes in two flavors: yellow marrow, which simply stores fat, and red marrow, which creates new blood cells. Thanks to the red marrow, your bones are nonstop assembly lines, churning out more than 100 billion blood cells everyday—important work indeed. In fact, a bone somewhere in your body created every blood cell that’s circulating in your body right now.

Note

Yellow marrow is found in the middle of long bones, like those in your legs. Red marrow is found primarily in flatter bones, like your hip bones, breast bone, skull, and shoulder blades.

Clearly your bones deserve more respect than they usually get. So the next time you see a skull and crossbones slapped on a bottle of lethal toilet-bowl cleaner, take a moment to reflect on your bones and their life-giving role as your body’s bottomless blood bank.

Note

Bone marrow doubles as a supremely nutritious food delicacy (at least when it’s from some other creature’s bones). Packed with protein and unsaturated fat, it’s a key ingredient in Vietnamese pho soup and the highlight of Italian osso bucco (braised veal shanks). Some anthropologists even believe that marrow was a staple in the diet of our distant ancestors. The theory is that these early humans were inept hunters who rarely caught a good meal—so they spent most of their mealtime cracking open the bones that more capable predators left behind.

Joints

On their own, bones are a remarkable piece of biological machinery. But the true miracle just might be the way a skeleton that’s stronger than concrete still allows the supple movements of a ballet dance.

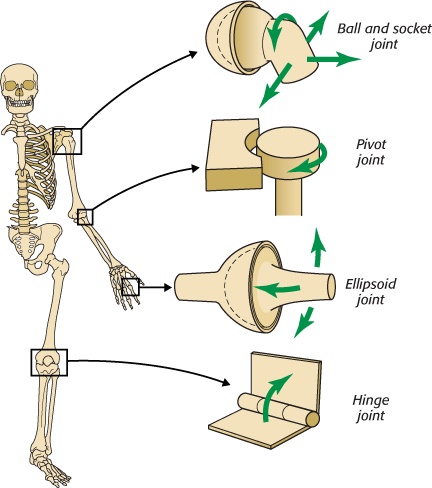

Joints are the means by which one bone glides, rotates, or bends around another. They ensure that your bones fit snugly together while allowing them an impressive range of movement. Different joints allow different types of movement—for example, joint limitations explain why you can’t spin your hand around your wrist or fold your head back until your ears rest on your shoulder blades. The image here shows four different joints, from the relatively simple folding joints at the knees and elbows to the more versatile ball-and-socket joints in your shoulders and hips.

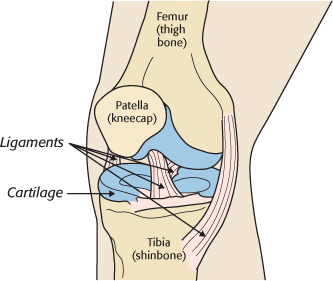

Joints are a surprisingly complex part of your skeleton. The bones in a joint are padded with cartilage, braced with ligaments, and lubricated with a special fluid. Here’s how each part works:

Cartilage. This tough, flexible tissue pads the end of the two bones that meet in a joint. Cartilage helps cushion and protect the joint, absorbing shocks and preventing friction. (Cartilage also supports other structures in your body—for example, it creates the shape of your ears and the tip of your nose.)

Ligaments. Ligaments are sturdy bands of elastic tissue that connect one bone to another. Your body often uses them to support a joint—for example, four major ligaments hold your knee in place and connect it to your leg bones.

Synovial fluid. This thick, stringy fluid fills many of your joints. It reduces friction between pieces of cartilage and other tissue in the joint, which helps reduce wear and tear.

Note

Synovial fluid is probably also responsible for the exquisitely annoying sound of knuckle cracking. The thinking is that over time, bubbles of gas accumulate in the synovial fluid of your joints. When you pull your finger ever-so-slightly out of place, the knuckle’s bones separate, and the tiny bubbles combine and burst in a distinctive pop. In theory, this practice could eventually cause loss of grip strength or joint pain, but so far no study has found knuckle cracking to cause anything more dangerous than a seriously annoyed spouse.

Incidentally, "double-jointed” people don’t have extra joints, just abnormally expanded joint movement for some other reason. They may have misaligned joints, for example, or abnormally shaped bones, or weaker ligaments and tendons. Alternatively, they may be less sensitive to the signals that indicate when the bones of a joint are out of place. Whatever the case, their condition puts them at higher risk of bone injury and arthritis.

Your Spine

Of all the bones in your body, few are as important as the stack of 33 that forms your spine.

Your spine (or vertebral column, as it’s known to biologists and Trivial Pursuit players) is the centerpiece of your skeletal system—your body’s equivalent of the center pole in a circus tent. It anchors your body, allowing you to stand upright, support your head and arms, and keep your balance. It’s a central attachment point for countless muscles, and it encases your critically important spinalcord, which ferries commands from your brain to the far regions of your body (and sends sensory information in the reverse direction, from your body parts back to your brain).

Your spine is also one of the easiest parts of your body to injure—poor posture, repetitive actions, or heavy lifting can easily drive you to the medicine cabinet or leave you lying helplessly under an office table. In fact, back pain affects 80 percent of adults at some point, and nearly half of them suffer at least one bout of back pain every year. In the U.S., lower-back pain is the fifth most common reason for doctor visits.

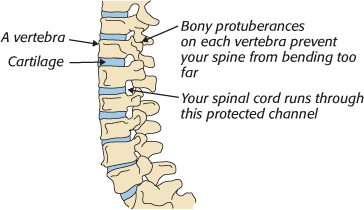

Part of the reason your spine is so vulnerable is its complexity. Of its 33 bones, 24 are bony disks called vertebrae. Every two vertebrae form a separate joint, each with its own ligaments holding it together and its own tendons binding it to the appropriate muscles. This design lets you freely bend and twist your spine. Your body limits your range of motion not with the ligaments themselves, but with the bony protrusions of each vertebra, which lock together if you try to bend them past a certain point. This important safeguard prevents a strained back from causing life-threatening paralysis.

Between each pair of vertebrae is a spongy disk of cartilage. These disks become temporarily more compressed throughout the day, and permanently more compressed as you age. They’re the reason you go to bed a little bit shorter than when you woke up, and why you’re likely to lose an inch of height by the time you reach old age. They’re also the source of more serious, long-term back ailments. For example, the infamous "slipped disk” occurs when you inadvertently crush a piece of cartilage out of shape, making it bulge into a nearby nerve.

Posture and Pain

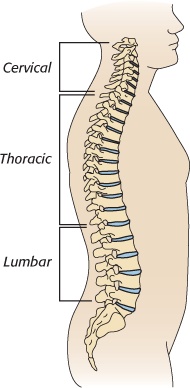

Your back puts up with a great many indignities. Ordinarily, your spine adopts three natural curves that help distribute your body’s weight. They go by the names cervical, thoracic, and lumbar curves.

No matter how good your posture, when you stay in a single position for a long time (for example, when you stand in line, sit at a desk, or drive across the country), you put increased pressure on parts of your spine, and you usually end up flattening or excessively curving these parts of your back. Your muscles strain to compensate, causing problems that range from a stiff neck to an aching lower back.

There’s no ironclad defense against back problems. However, you can do a lot by observing good posture, practicing back-strengthening exercises (see Back Strengthening), and avoiding back-straining experiences.

The first rule of good posture is to vary your position. Contrary to what you might think, good posture doesn’t involve locking your back into an ideal arrangement for hours at a time. In fact, the human back hasn’t quite caught up to the strains and stresses of modern-day activities like sitting in motor vehicles and doing office work. You’ll spare your spine a lot of pain by interrupting long, tedious activities (driving, typing, and so on) to take a quick stretch and have a walk around. If you can, limit yourself to 20 minutes of focused office work or an hour of uninterrupted driving before you take a quick refresher.

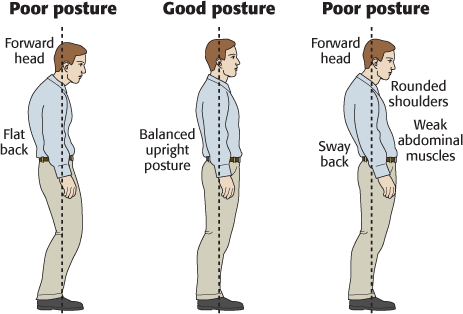

The next step is to learn an invaluable skill: recognizing poor posture. If you can catch yourself when you start to slouch, you can stave off soreness, stiffness, and injury. The following sections show you how.

Standing posture

Standing is a seemingly simple activity that the human body doesn’t do very well. Our bodies are designed to handle much more ambitious activities (climbing hills, hunting elk, and so on). Keep us stuck in one place, and we suffer—our backs ache, our posture slips, and we end up with more spinal distress than a performer in Cirque du Soleil.

During short periods of standing, you can reduce strain by avoiding the worst mistakes. Keep your head, shoulders, and feet lined up (imagine a straight line that links the top of your head to the middle of your feet). The biggest backaches start when you pull your head forward or lean your upper body backward.

If you must stand for a long time, shift your weight from one foot to the other or rock your feet from heel to toe. Putting one foot on a very low rail, like the sort you find at some bars, can also reduce the pressure on your back. Posture experts say leaning is acceptable, but only if you put your lower back, shoulders, and the back of your head against a wall—a position that might draw a few curious stares.

Sitting posture

It’s often said that the rear end is the most heavily used part of the human body. If you’re an average person living in the modern world, you spend a lot of time pressing your behind into soft, yielding pieces of furniture. In fact, you probably spend more time sitting down (whether it’s working, eating, driving, watching television, or reading fine books like this one) than you spend in virtually any other position.

With all our experience sitting, it’s a bit disappointing to learn that most of us aren’t very good at it. Proper sitting is surprisingly hard work, especially when you add computers, telephones, and office work into the mix. Part of the problem is that sitting “at the ready” quickly becomes tiring, and good posture requires constant vigilance. One funny Web video later, and you’ll be slouching into your computer screen.

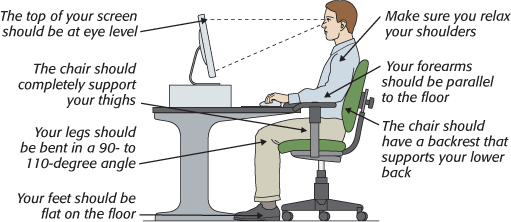

The first piece of advice for long-term sitters is to take frequent breaks. (You can find some simple stretches and exercises you can do without leaving your desk at http://backandneck.about.com/od/exercise/ig/Stretch-at-Your-Desk.) The second piece of advice is to conduct regular “posture checks.” With each posture check, your goal is to review what you’re doing and pull your body back into line. The most common mistakes include pushing out your stomach (which curves and overextends your back), hunching your shoulders, and craning your neck. To make sure you’re sitting pretty, use the picture on this page as a quick posture checklist.

Lifting posture

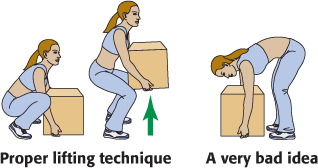

One of the easiest ways to injure your back is through careless lifting. A proper lifting technique looks a bit like the squat exercise you saw on 1. Squats. Like the squat, it involves crouching down and using the strong muscles in your legs to do the brunt of the lifting, minimizing the stress you put on your back and reducing the amount you bend your spine.

A little preparation can make all the difference in proper lifting. Before you grab the object in front of you, adopt a wide, crouched stance. Make sure your feet rest firmly on the floor and that your back is straight, not hunched. Stand slowly, avoid twisting to the side, and concentrate on pushing with your legs, rather than pulling with your back.

Sleeping posture

We’re not about to crawl between the sheets with you and prescribe stiff rules about how to position your sleeping body. However, if you already suffer from bouts of back pain (whether caused by long hours of office work, heavy lifting, or pregnancy), you might find that sleeping in your regular positions is about as comfortable as having a prickly pear in your pajama bottoms. In this situation, you can try two tricks.

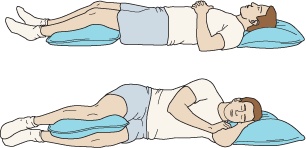

First, if you’re a back sleeper, place a pillow under your knees. This takes the strain off your lower back. (If you want to adopt this position permanently, look for a wedge-shaped specialty pillow at a pharmacy or health store.) Second, if you sleep on your side, put a pillow between your knees. Again, this helps keep your spine in the straight, neutral alignment it likes best.

Back Strengthening

Weak back muscles just can’t support your spine and battle gravity for an entire day. If you want your spine to stay healthy and pain-free, your best bet is to strengthen your back muscles with regular exercise.

Ideally, you’ll fortify your back with aerobic exercise (walking, running, dancing, and so on) and regular strength-training workouts like the ones described in the previous chapter. Core exercises like abdominal crunches (5. Abdominal Crunch) are particularly helpful because they reinforce the back and abdominal muscles that stabilize and support your spine.

Note

If you have a pre-existing back condition or chronic back pain, doing the wrong kind of exercise (or doing the right exercise in the wrong way) could aggravate the problem. If you’re in doubt, check with your doctor, and never perform a back exercise that causesany sort of pain.

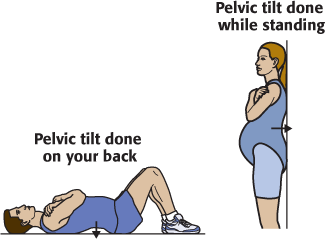

The single most useful exercise for strengthening your back and relieving back pain is surprisingly simple and remarkably portable. You can do it on the floor of your home gym, in the chair at your office desk, or against the wall at a cocktail party. Pregnant women can use it to alleviate the excruciating backaches caused by their still-in-progress bundle of joy (on the floor up to the fourth month, against a wall thereafter). It goes by many names, including the one used in this chapter: the pelvic tilt.

Here’s how to do the pelvic tilt:

Lie on your back with your knees bent and your hands resting at your sides. (Or stand so you put your whole body—heels, bottom, and shoulders—against a wall.)

Tighten your abdominal muscles and squeeze your lower back down against the floor (or wall, or chair). Alternatively, you can rest your hand on the small of your back and push against that.

Hold the squeeze for five seconds, but don’t hold your breath.

Relax your muscles, then repeat this sequence 10 to 15 times.

Note

You can find many of the core exercises cited in this chapter described online. To get started, you’ll find good collections of back exercises at www.mayoclinic.com/health/back-pain/LB00001_D and http://tinyurl.com/cyybg9. (To save yourself some typing, you can find this link on the Missing CD page at www.missingmanuals.com.)

Get Your Body: The Missing Manual now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.