The World Wide Web has changed our world. More than half the people in the United States now use the Web on a regular basis. We use it to read today’s news, to check tomorrow’s weather, and to search for events that have happened in the distant past. And increasingly, the Web is the focus of the 21st century economy. Whether it’s the purchase of a $50 radio or the consummation of a $5 million business-to-business transaction, the Web is where the action is.

But the Web is not without its risks. Hand-in-hand with stories of the Internet’s gold rush are constant reminders that the 21st century Internet has all the safety and security of the U.S. Wild West of the 1860s. Consider:

In February 2000, web sites belonging to Yahoo, Buy.com, Amazon.com, CNN, E*Trade, and others were shut down for hours, the result of a massive coordinated attack launched simultaneously from thousands of different computers. Although most of the sites were back up within hours, the attacks were quite costly. Yahoo, for instance, claimed to have lost more than a million dollars per minute in advertising revenue during the attack.

In December 1999, an attacker identifying himself as a 19-year-old Russian named “Maxim” broke into the CDUniverse web store operated by eUniverse Inc. and copied more than 300,000 credit card numbers. Maxim then sent a fax to eUniverse threatening to post the stolen credit cards on the Internet if the store didn’t pay him $100,000.[1] On December 25, when the company refused to bow to the blackmail attack, Maxim posted more than 25,000 of the numbers on the hacker web site "Maxus Credit Card Pipeline.”[2] This led to instances of credit card fraud and abuse. Many of those credit card numbers were then canceled by the issuing banks, causing inconvenience to the legitimate holders of those cards.[3] Similar break-ins and credit card thefts that year affected RealNames,[4] CreditCards.com, EggHead.Com, and many other corporations.

In October 2000, a student at Harvard University discovered that he could view the names, addresses, and phone numbers of thousands of Buy.com’s customers by simply modifying a URL that the company sent to customers seeking to return merchandise. “This blatant disregard for security seems pretty inexcusable,” the student, Ben Edelman, told Wired News.[5]

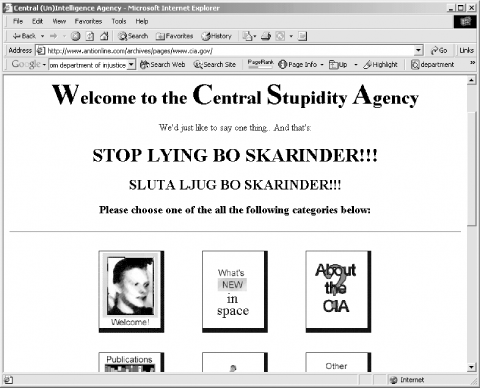

Attacks on the Internet aren’t only limited to e-commerce sites. A significant number of high-profile web sites have had their pages rewritten during attacks. Those attacked include the U.S. Department of Justice, the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (see Figure P-1), the U.S. Air Force, UNICEF, and the New York Times. An archive of more than 325 hacked home pages is online at http://www.antionline.com/.

Figure 1. On September 18, 1996, a group of Swedish hackers broke into the Central Intelligence Agency’s web site (http://www.odci.gov/) and altered the home page, proclaiming that the Agency was the Central Stupidity Agency.

Attacks on web servers are not the only risks we face on the electronic frontier:

On August 25, 2000, a fraudulent press release was uploaded to the computer of Internet Wire, an Internet news agency. The press release claimed to be from Emulex Corporation, a maker of computer hardware, and claimed that the company’s chief executive officer had resigned and that the company would have to adjust its most recent quarterly earnings to reflect a loss, instead of a profit. The next morning, Emulex’s share price plunged by more than 60%: within a few hours, the multi-billion-dollar company had lost roughly half its value. A few days later, authorities announced the Emulex caper had been pulled off by a single person—an ex-employee of the online news service, who had made a profit of nearly $250,000 by selling Emulex stock short before the release was issued.

Within hours of its release on May 4, 2000, a fast-moving computer worm called the "Love Bug” touched tens of millions of computers throughout the Internet and caused untold damage. Written in Microsoft Visual Basic Scripting Language (VBS), the worm was spread by people running the Microsoft Outlook email program. When executed, the worm would mail copies of itself to every email address in the victim’s address book, then destroy every MP3 and JPEG file that it could locate on the victim’s machine.

A growing number of computer “worms” scan the victim’s hard disk for Microsoft Word and Excel files. These files are infected and then sent by email to recipients in the victim’s address book. Not only are infections potentially started more often, but confidential documents may be sent to inappropriate recipients.

The Web doesn’t merely represent a threat for corporations. There are cyberstalkers, who use the Web to learn personal information and harass their victims. There are pedophiles, who start relationships with children and lure them away from home. Even users of apparently anonymous chat services aren’t safe: In February 1999, the defense contracting giant Raytheon filed suit against 21 unnamed individuals who made disparaging comments about the company on one of Yahoo’s online chat boards. Raytheon insisted that the 21 were current employees who had leaked confidential information; the company demanded that the Yahoo company reveal the identities behind the email addresses. Yahoo complied in May 1999. A few days later, Raytheon announced that four of the identified employees had “resigned,” and the lawsuit was dropped.[6]

Even using apparently “anonymous” services on the Web may jeopardize your privacy and personal information. A study of the 21 most visited health-related web sites on the Internet (prepared for the California HealthCare Foundation) discovered that personal information provided at many of the sites was being inadvertently leaked to third-parties, including advertisers. In many cases, these data transfers were in violation of the web sites’ own stated privacy policies.[7] A similar information leak, which sent the results of home mortgage calculations to the Internet advertising firm DoubleClick, was discovered on Intuit’s Quicken.com personal finance site.[8]

We have been incredibly lucky. Despite the numerous businesses, government organizations, and individuals that have found danger lurking on the Web, there have been remarkably few large-scale electronic attacks on the systems that make up the Web. Despite the fact that credit card numbers are not properly protected, there is surprisingly little traffic in stolen financial information. We are vulnerable, yet the sky hasn’t fallen.

Today most Net-based attackers seem to be satisfied with the publicity that their assaults generate. Although there have been online criminal heists, there are so few that they still make the news. Security is weak, but the vast majority of Internet users still play by the rules.

Likewise, attackers have been quite limited in their aims. To the best of our knowledge, there have been no large-scale attempts to permanently crash the Internet or to undermine fundamental trust in society, the Internet, or specific corporations. The New York Times had its web site hacked, but the attackers didn’t plant false stories into the newspaper’s web pages. Millions of credit card numbers have been stolen by hackers, but there are few cases in which these numbers have been directly used to commit large-scale credit fraud.

Indeed, despite the public humiliation resulting from the well-publicized Internet break-ins, none of the victimized organizations have suffered lasting harm. The Central Intelligence Agency, the U.S. Air Force, and UNICEF all still operate web servers, even though all of these organizations have suffered embarrassing break-ins. Even better, none of these organizations actually lost sensitive information as a result of the break-ins, because that information was stored on different machines. A few days after each organization’s incident, their servers were up and running again—this time, we hope, with the security problems fixed.

The same can be said of the dozens of security holes and design flaws that have been reported with Microsoft’s Internet Explorer and Netscape Navigator. Despite attacks that could have allowed the operator of some “rogue web site” to read any file from some victim’s computer—or even worse, to execute arbitrary code on that machine—surprisingly few scams or attacks make use of these failings.[9] This is true despite the fact that the majority of Internet users do not download the security patches and fixes that vendors make available.

In the world of security it is often difficult to tell the difference between actual threats and hype. There were more than 200 years of commerce in North America before Allan Pinkerton started his detective and security agency in 1850,[10] and another nine years more before Perry Brink started his armored car service.[11] It took a while for the crooks to realize that there was a lot of unprotected money floating around.

The same is true on the Internet, but with each passing year we are witnessing larger and larger crimes. It used to be that hackers simply defaced web sites; then they started stealing credit card numbers and demanding ransom; in December 2000, a report by MSNBC detailed how thousands of consumers had been bilked of between $5 and $25 on their credit cards by a group of Russian telecommunications and Internet companies; the charges were small so most of the victims didn’t recognize the fraud and didn’t bother to report the theft.[12]

Many security analysts believe things are going to get much worse. In March 2001, the market research firm Gartner predicted there would be “at least one incident of economic mass victimization of thousands of Internet users . . . by the end of 2002:”[13]

“Converging technology trends are creating economies of scale that enable a new class of cybercrimes aimed at mass victimization,” explain[ed] Richard Hunter, Gartner Research Fellow. More importantly, Hunter add[ed], global law enforcement agencies are poorly positioned to combat these trends, leaving thousands of consumers vulnerable to online theft. “Using mundane, readily available technologies that have already been deployed by both legitimate and illegitimate businesses, cybercriminals can now surreptitiously steal millions of dollars, a few dollars at a time, from millions of individuals simultaneously. Moreover, they are very likely to get away with the crime.”

Despite these obvious risks, our society and economy has likely passed a point of no return: having some presence on the World Wide Web now seems to have become a fundamental requirement for businesses, governments, and other organizations.

It’s difficult for many Bostonians to get to the Massachusetts Registry of Motor Vehicles to renew their car registrations; it’s easy to click into the RMV’s web site, type a registration number and a credit card number, and have the registration automatically processed. And it’s easier for the RMV as well: their web site is connected to the RMV computers, eliminating the need to have the information typed by RMV employees. That’s why the Massachusetts RMV gives a $5 discount to registrations made over the Internet.

Likewise, we have found that the amount of money we spend on buying books has increased dramatically since Amazon.com and other online booksellers have opened their web sites for business. The reason is obvious: it’s much easier for us to type the name of a book on our keyboards and have it delivered than it is for us to make a special trip to the nearest bookstore. Thus, we’ve been purchasing many more books on impulse—for example, after hearing an interview with an author or reading about the book in a magazine.

Are the web sites operated by the Massachusetts RMV and Amazon.com really secure? Answering this question depends both on your definition of the word “secure,” and on a careful analysis of the computers involved in the entire renewal or purchasing process.

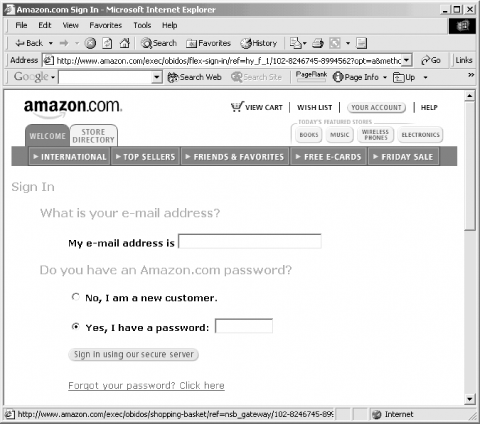

In the early days of the World Wide Web, the word “secure” was promoted by Netscape Communications to denote any web site that used Netscape’s proprietary encryption protocols. Security was equated with encryption—an equation that’s remained foremost in many people’s minds. Indeed, as Figure P-2 clearly demonstrates, web sites such as Amazon.com haven’t changed their language very much. Amazon.com invites people to “Sign in using our secure server,” but is their server really “secure”? Amazon uses the word “secure” because the company’s web server uses the SSL (Secure Sockets Layer) encryption protocol. But if you click the link that says “Forgot your password? Click here,” Amazon will create a new password for your account and send it to your email address. Does this policy make Amazon’s web site more secure or less?

Figure 2. Amazon.com describes their server as “secure,” but the practice of emailing forgotten passwords to customers is hardly a secure one.

Over the Web’s brief history, we’ve learned that security is more than simply another word for cryptographic data protection. Today we know that to be protected, an organization needs to adopt an holistic approach to guarding both its computer systems and the data that those systems collect. Using encryption is clearly important, but it’s equally important to verify the identity of a customer before showing that customer his purchase history and financial information. If you send out email, it’s important to make sure that the email doesn’t contain viruses—but it is equally important to make sure that you are not sending the email to the wrong person, or sending it out against the recipient’s wishes. It’s important to make sure that credit card numbers are encrypted before they are sent over the Internet, but it’s equally important to make sure that the numbers are kept secure after they are decrypted at the other end.

The World Wide Web has both promises and dangers. The promise is that the Web can dramatically lower costs to organizations for distributing information, products, and services. The danger is that the computers that make up the Web are vulnerable. These computers have been compromised in the past, and they will be compromised in the future. Even worse, as more commerce is conducted in the online world, as more value flows over the Internet, as more people use the network for more of their daily financial activities, the more inviting a target these computers all become.

Get Web Security, Privacy & Commerce, 2nd Edition now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.