Chapter 4. Branding

As you go through the customer development and market research processes, you are collecting valuable information that will help you formulate a brand identity. Your brand is the personification of your company, and developing a strong brand is absolutely critical to your success. It builds a foundation for a long-term relationship with customers.

Branding can feel like a rather elusive concept, as the value-add of a strong brand is difficult to quantify and measure. Startups often undervalue the importance of building a brand, particularly if the founding team is strong on tech but has no marketing or sales experience (as is often the case). In any early-stage company, there is much to do and precious few resources to do it with. There is never enough time, money, or people, so most founders put all of their resources toward nailing the product. Branding, marketing, sales strategy…those are problems to push off until a later date.

Don’t make this mistake.

The problem with this approach for a hardware company is that your product will be competing for shelf space (digital or physical) with established players. When you are on a physical shelf, there is no website with help text or comparison charts that can explain the virtues of your product. Your package messaging must be appealing enough to convince a busy shopper to put your widget into her cart. If your product is on the shelf next to one of similar price manufactured by a competitor who has better name recognition, your product is at a disadvantage. People have many choices, but little time. They’re going to grab the product they’ve heard of, or the brand they are loyal to.

While startups often neglect brand building, Fortune 500 companies prioritize it. They treat branding as a critical facet of their business strategy. A study by Interbrand and JP Morgan determined that, on average, brand accounts for close to a third of shareholder value. Though valuing intangibles is notoriously difficult, the study says:

The brand is a special intangible that in many businesses is the most important asset. This is because of the economic impact that brands have. They influence the choices of customers, employees, investors and government authorities. In a world of abundant choices, such influence is crucial for commercial success.

In 2013, Apple was the most valuable brand name in the world, worth an estimated $98.3 billion. Google was second on the list, at $93.3 billion, and Coca-Cola was third, with $79.2 billion.

Brand equity is the monetary value that comes from having a recognizable brand. Marketing experts have found that positive name association enables a company to justify a price premium over similar goods. Think of the product options on the shelf of your drugstore: is Clorox bleach better than store-brand bleach? Is Advil better than generic ibuprofen? In both cases, the generic is exactly the same product, but it costs more. And yet, people still buy it. That price premium is Clorox’s and Advil’s brand equity.

In the world of devices, your product is not exactly the same as your competitor’s product. At a minimum, you likely have a few different features and a different design. But when customers are deciding what to buy, they are purchasing a product to meet a need or fulfill a want. If either your device or your competitor’s device will satisfy their objectives for approximately the same price, brand becomes a powerful differentiator.

Emotional responses to products matter. According to Alina Wheeler’s seminal brand-strategy guide Designing Brand Identity (Wiley), brands serve three primary functions:

- Navigation

-

A strong brand helps customers make a choice when presented with a wide array of options.

- Reassurance

-

In a world with so many choices, a brand reassures customers that the product they’ve chosen is high quality and trustworthy.

- Engagement

-

Brand visuals and communications make customers feel that the brand understands them. The result is that customers identify with the brand.

A recognizable brand can help a company increase (or defend) its market share by inspiring trust and enhancing the perception of quality. Having customers who identify with your brand engenders loyalty.

Brand loyalty is important in an industry in which product turnover is high. Within a few years, new technology renders many hardware products outdated. People upgrade consumer electronics (phones, music players, cameras, speakers) every few years. High-quality software products are developed to engender what’s known as lock-in: over time, customers become accustomed to the feature set, learn advanced shortcuts, store their data, or create large libraries of files. They become loyal customers and will often pay to upgrade the software as new versions are released. They have invested time and energy in learning how to use it, and this makes them reluctant to switch to a new product. This phenomenon is particularly prevalent in enterprise software, where corporations want to ensure continuous availability of data and internal documents. They don’t want to risk losing document integrity porting to a new product.

With most hardware products, this kind of lock-in is difficult to achieve. Unlike with software, where you can push an update that incorporates new technology (and suggest that your users buy it), hardware upgrades eventually require new physical components encased in new plastic. At the point of purchase, whether on the shelf or online, your customers will be confronted by alternatives. Strong branding generates loyalty and makes customers more likely to have you top-of-mind when they intend to purchase; even when they’re not actively intending to purchase, you want your brand to be top-of-mind.

Besides loyalty, a strong brand gives you leverage when expanding your offering into a new category. This is a particularly important consideration for connected-device startups or for wearables companies that aspire to be platforms. According to Sean Murphy of product development consultancy Smart Design (see his discussion of branding and design in “From Conception to Prototype with Smart Design: A Case Study”), “There really aren’t ‘connected products’; there are just connected brands. You don’t just experience the product; you experience an ecosystem.”

Jawbone started out as company called Aliph; Jawbone was the name of its first wireless headset. It released several subsequent models of headsets over the years—Jawbone Prime, Jawbone Icon, Jawbone Era—before eventually dropping the name Aliph and rebranding as simply Jawbone. Under the successful Jawbone brand, the company expanded from headsets into portable speakers (Jawbone Jambox) and then a fitness device (Jawbone Up). The packaging for each of these devices reads: “ERA by Jawbone,” “UP by Jawbone,” etc.

Prioritizing brand recognition gives a company a leg up on a new launch, in terms of both awareness and perception of quality. Regardless of the distribution channels you pursue, you won’t sell many widgets if you’re an unknown quantity.

So how do you build a recognizable brand?

Your Mission

First and foremost, a brand must have a mission. Earlier in this chapter, we touched on the importance of identifying a problem that truly motivates you and resonates with others. Your mission is what your company is doing, why, and for whom. You should be able to articulate this succinctly in the form of an elevator pitch or mission statement (sometimes called a mantra). Your brand mantra is a statement of why you exist. Consider the following examples:

- Apple

-

“Committed to bringing the best personal computing experience to students, educators, creative professionals, and consumers around the world through its innovative hardware, software, and Internet offerings.”

- Microsoft

-

“To enable people and businesses throughout the world to realize their full potential.”

- Nike

-

“To bring inspiration and innovation to every athlete* in the world. (*if you have a body, you are an athlete)”

-

“To organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful.”

These sentences distill each company’s intent and purpose into a single statement that represents the core of the brand’s identity. All other facets of branding—personality, assets, and experience—are outgrowths of this statement of purpose.

The company’s products also reflect this purpose. Consider Apple’s and Microsoft’s mission statements in the context of their product lines. Apple builds beautiful products and prioritizes a seamless user experience. Microsoft builds exemplary productivity tools used in enterprise companies all over the world.

Knowing your mission helps your company in both an internal and a public-facing capacity. Internally, it serves as a guide for employees to know what they stand for and what they’re working toward. It provides a company with a framework to evaluate strategies and products: to what extent does a specific action or product release advance your mission and align with your core values?

Sean Murphy (see his discussion of branding and design in “From Conception to Prototype with Smart Design: A Case Study”) points out:

There’s a tremendous pressure to cut corners when you’re a startup. Having strong brand principles gives you something to refer back to during development. As the product evolves, you’re going to make decisions with respect to what you understand your brand to be. The software, the service components…it will all be viewed in the context of answering the question “Who are we?”

Publicly, your mission statement is a communication tool that frames your brand in the minds of consumers. You are telling people what you stand for and why you exist. In his book Grow (Crown Business), marketing expert and former Procter & Gamble global marketing officer Jim Stengel advocates that a company should have a brand ideal, a “higher-order benefit it brings to the world” that satisfies a fundamental human value that improves people’s lives. In his own words, people’s lives can be improved by engaging five fundamental human values:

- Eliciting Joy

-

Activating experiences of happiness, wonder, and limitless possibility.

- Enabling Connection

-

Enhancing the ability of people to connect with each other and the world in meaningful ways.

- Inspiring Exploration

-

Helping people explore new horizons and new experiences.

- Evoking Pride

-

Giving people increased confidence, strength, security, and vitality.

- Impacting Society

-

Affecting society broadly, including by challenging the status quo and redefining categories.

These ideals elicit emotional responses. Emotional connections lead to deeper relationships with customers. Brand communication skills expert Carmine Gallo has interviewed numerous CEOs about what their brands stand for. He recalls Tony Hsieh, founder of Zappos, replying with one word: “happiness.” Richard Branson, CEO of Virgin Group: “fun.”

New founders might be skeptical of the real impact of values and ideals on important metrics, such as sales numbers. While a direct link is difficult to quantify, Stengel cites a study that examined the connection between financial performance and customer engagement and loyalty over a 10-year period. The researchers looked at 50,000 brands and found that in the minds of consumers, the 50 top high-growth brands were linked with an ideal. These 50 companies (called the “Stengel 50”) grew three times as fast as their competitors over the 10-year period. One example of such a company is Pampers:

Pampers’ brand ideal, for example, its true reason for being, is not selling the most disposable diapers in the world. Pampers exists to help mothers care for their babies’ and toddlers’ healthy, happy development. In looking beyond transactions, an ideal opens up endless possibilities, including endless possibilities for growth and profit.

You can’t be all things to all people. A well-defined set of values and authentic messaging will help you attract customers who share your values and vision, and care about what you are trying to do for the world. As a startup, it can also help you find investors and potential employees who are aligned with your mission.

Brand Identity and Personality

Putting in the effort to arrive at a deep understanding of your brand’s values and mission will help you define and project a coherent brand identity. As defined in branding expert and author of The Brand Gap (New Riders) Marty Neumeier’s The Dictionary of Brand (an excellent resource for brand builders), brand identity is “the outward expression of a brand, including its trademark, name, communications, and visual appearance.”

Brand identity is the sum of all of the parts. Identity is deliberately constructed by the company, with the goal of ensuring that customers both recognize the brand as an entity and can articulate how it differs from the competition. Brand image is the consumer’s perception of this identity: how the market views your brand. You want the market view to align with the impression you are trying to create.

As Neumeier puts it, “[A brand] is not what you say it is, it’s what they say it is.” To have an impact on your brand image, you must actively manage your brand identity.

Professional brand strategists use a variety of methods and frameworks to define and shape identity. In Designing Brand Identity, Alina Wheeler breaks down the process into five steps:

- Conducting Research

-

Fully investigate the existing perception of the brand, both in the market and in the minds of stakeholders (constituents who have a vested interest in a company, such as employees, investors, customers, partners, etc.).

- Clarifying Strategy

-

Define goals, identify key messages, and determine appropriate strategies for naming, branding, and positioning.

- Designing Identity

-

Define a unifying “big idea” and develop a visual strategy.

- Creating Touchpoints

-

Produce visual elements, refine the look and feel, and protect trademarks.

- Managing Assets

-

Develop and implement a launch strategy to unveil brand elements, define brand standards, and establish guidelines to ensure consistency.

This process might seem like an extensive undertaking, particularly for a resource-constrained startup, and it can be a long and time-consuming process. But even in the days before a startup has stakeholders aside from the team, it should be thinking about brand identity. Jinal Shah of marketing communications firm J. Walter Thompson (JWT) discusses ways that startups can streamline this process in “Brand Building for Startups: A Case Study”.

A fundamental component of brand identity is brand personality. Emotions are involved in the purchasing process, as the customer has a need or desire and is looking to fulfill it. Consumers buy products that fit the perception they have of themselves, or the way they wish to be perceived by others.

A successful brand has a clearly defined personality that appeals to or resonates with its target customers. In The Dictionary of Brand, Marty Neumeier defines brand personality as “the character of a brand as defined in anthropomorphic terms.” Brands can be kind, funny, masculine, elegant…the possibilities are endless.

Agencies use several common frameworks to help their clients identify a brand personality, some of which a research-constrained startup can carry out independently. One is an archetype study. Archetypes are a universal model for a personality, such as “the Joker” or “the Rebel.” Hardware startup Contour Cameras took this approach, which founder Marc Barros described in a blog post about the process: “Defining a brand is like defining a person. No different from how you would describe a friend, brand attributes are the adjectives you choose to define the personality of your brand.”

Using the 12 archetypes defined in Margaret Mark and Carol Pearson’s book The Hero and the Outlaw (McGraw-Hill), the Contour team identified the persona that fit their desire to facilitate imaginative self-expression: the Creator. Using the Creator as an anchor, they focused their brand on creativity. They worked on producing a product that would be loved by Creator types: artists, innovators, and dreamers.

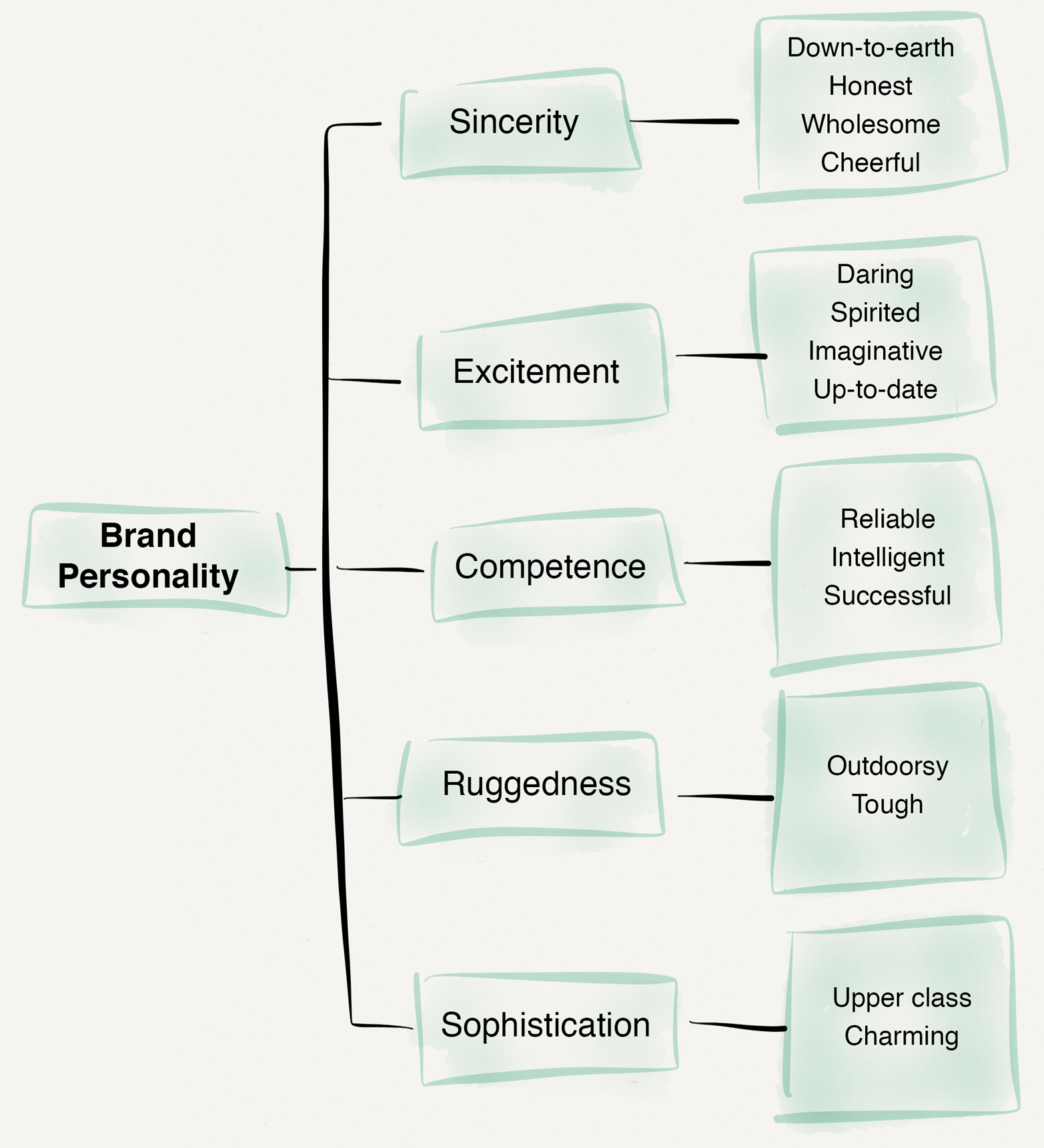

In psychological research, the five-factor model asserts that there are five basic dimensions of human personality (called “the Big Five personality traits”): openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism. In a similar vein, Stanford marketing professor Dr. Jennifer Aaker believes that brand personality can be broken down into five core dimensions: sincerity, excitement, competence, sophistication, and ruggedness. Within each of these dimensions are facets and traits that increase the specificity of the description, as shown in Figure 4-1. While some academics have criticized Aaker’s scale as biased toward American culture, these lists of traits are a solid jumping-off point for companies looking to define their brand personality.

Figure 4-1. Aaker’s brand dimensions

Another approach to the process involves listing adjectives that describe your target customer. Some branding agencies have their clients work through association exercises, such as “If you were a car, what kind of car would you be?” or “If you were an animal, what kind of animal would you be?” Or you could try personification: imagine your brand as a real person and visualize what she would look like and how she would act.

Products and messaging keep changing over time as a company evolves, but brand values and personality generally remain the same. Jinal Shah says:

You want to have a little bit of room to evolve and have fluidity in the market, but there is still a core set of values that must remain consistent. Think about you, the person. There are certain things that you would do or say, and certain things that you would not do or say. People who know you can probably distinguish between the two. That’s how your personal brand gets built. It’s no different for a company.

Brand Assets and Touchpoints

Brand personality is brought to life via brand assets. Assets include the brand name, logo, tagline, graphics, color palettes, and sounds…sometimes even scents and tastes.

Naming your company is incredibly important. A name is the most frequently used brand asset. Customers see it and hear it. They speak it when they tell their friends about you. Many blog posts have been written about naming software startups: common suggestions include keeping the name short, choosing something with an available domain (or, at worst, a unique modified domain with the name in the title, such as GETstartup.com or startupHQ.com) and social media handles, and selecting something that is easily pronounceable and searchable (don’t remove too many vowels!). A name should be distinctive and memorable. It must also be legally available and not trademarked by anyone else.

One important difference between naming a hardware startup (or product) and a software startup is that the name is more likely to appear on packaging, and possibly on the device. Clarity and readability are critical. Can you tell from a glance at the name what the product does? The ability to extend a product line in the future is also something to consider. Apple has done this exceptionally well. The “iDevice” naming convention has taken it through decades of hardware products (iMac, iBook, iPod, iPhone, iPad), and links the hardware to the software (iTunes).

Some companies use their founder’s names. That way a corporate brand can benefit from being associated with a charismatic founder’s personal brand (Beats by Dre), but there is a risk of negative associations if the founder endures any personal scandal or hardship (Martha Stewart). Also, be wary of choosing a name that is a generic word. While many successful companies have such names (such as Square and Nest), it takes hard work to associate the word with your company in the minds of consumers. You’ll also spend quite a bit of money acquiring the domain.

Begin your naming process by deciding what you most want the name to evoke. You can use the work you did when identifying your values and personality. Choose several words or phrases that capture the brand essence you’re going for, and begin to brainstorm. There are many categories from which to pick a name:

-

Emotions that you want your product to evoke

-

Locations where people are likely to use it

-

A distinctive physical characteristic of the product

-

A metaphor that represents your user or your product

-

A verb related to your product’s functionality

It’s helpful to work through this process with a group of people. Word association and building off of the creativity of others can make it a lot easier and more enjoyable.

Once you’ve come up with several names that you like (and checked them for potential trademark infringement), it’s time to test them. San Francisco naming consultancy Eat My Words has a series of criteria that it calls the SMILE & SCRATCH test.

The SMILE test checks to see if your name has the following important qualities:

- Suggestive — evokes a positive brand experience

- Meaningful — your customers “get it”

- Imagery — visually evocative to aid in memory

- Legs — lends itself to a theme for extended mileage

- Emotional — resonates with your audience

And the SCRATCH test helps you determine if it should be scrapped:

- Spelling-challenged — looks like a typo

- Copycat — similar to competitor’s name

- Restrictive — limits future growth

- Annoying — forced

- Tame — flat, uninspired

- Curse of knowledge — only insiders get it

- Hard-to-pronounce — not obvious, unapproachable

If your name passes these two tests, it’s time to consider testing it in the wild. Some entrepreneurs choose not to, instead just trusting their own judgment. Others solicit feedback solely from friends, family, or their (early) community. Naming and branding experts advise field testing, because it’s often difficult for insiders to recognize that their name has a “curse of knowledge” problem or is inscrutable to a general audience. They test names with focus groups. Common questions that naming experts ask include:

-

What do you think this business does?

-

Can you spell it? (Can you pronounce it?)

-

Does this name remind you of any particular product?

-

What do you think of when you read the name?

If you’re bootstrapping this process and decide you want to get consumer feedback on your product name, online surveys are a less expensive and less time-consuming way to go. You can reach a wide audience for a minimal fee using a service such as Mechanical Turk or Crowdflower to find survey participants. Some founders try A/B testing names in AdWords, driving traffic to landing pages.

Still, there’s no substitute for in-person feedback whenever you can get it. Marc Barros, the founder of wearable-camera maker Contour, describes its process of using the “Bar Test”: say your company name to someone in a noisy bar. See if they understand what you do. If they can’t pronounce or spell the name, consider it a failure. (For more lessons learned from Marc’s experience with company naming and branding, see “Naming Contour and Moment: A Case Study”.)

Your brand name and personality are the cornerstones for the rest of your visual assets: logo, graphics, color palettes, and icons—and you have many creative choices to make. Certain colors evoke specific emotions. A logo can be a word (“Google”), a picture (Apple’s apple), or a combination of the two (the 1992–2011 Starbucks logo). The goal is to create representative visuals that are immediately recognizable and memorable and that retain their impact when displayed across different mediums.

The sensory experience should be coherent and in line with the brand personality. For example, if your brand personality is elegant and sophisticated, a low-resolution cartoon animal logo would seem incongruous. Visual assets should fit cohesively with the look and feel of your product, including any software or apps experienced by the end user. For a good example of precise execution around visual identity, check out Google’s Visual Assets Guidelines.

Producing quality brand assets takes time and costs money. If you don’t have the resources or desire to work with a branding agency, your designer is the person most likely to be responsible for this process. If you don’t have someone with design experience on the team, hire an expert contractor. Brand assets might evolve over time, but you’ll want a polished appearance from day one. And just as with everything else in life, you get what you pay for. Expect to pay $50 to $100 an hour for a professional.

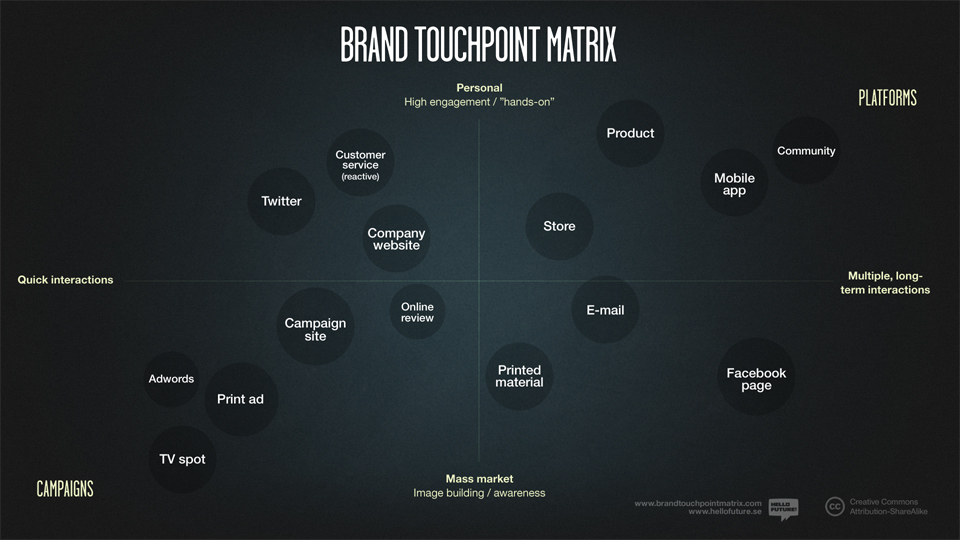

The points at which brands interact with consumers are called touchpoints. To identify touchpoints, think about your outreach channels: media, packaging, advertising, environment (e.g., stores). Possible touchpoints include websites, emails, apps, blogs, TV, trade shows, exhibits, print materials, circulars, billboards, videos, kiosks, retail shelves, social media…basically, anywhere in the physical or online world that a consumer might encounter your brand.

Touchpoints can be quick or sustained, personalized or mass-market, real-time or static. Product design consultancy Hello Future has an excellent matrix that illustrates this, as shown in Figure 4-2. Note the position of “campaigns” (advertising) at the bottom left: quick and mass-market. Up at the top right are “platforms,” which are long-term and sustained.

Figure 4-2. Hello Future’s Brand Touchpoint Matrix (used under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike license)

Consumers might encounter touchpoints at the prepurchase, purchase, or postpurchase stage. The goal of a prepurchase interaction is to shape a consumer’s perception of your brand and communicate your value proposition. You are attempting to increase the consumer’s likelihood of buying your product. At the point of purchase, the goal is not only to make the sale, but also to establish a deeper relationship. Postpurchase communications are geared toward building loyalty, ensuring satisfaction, and turning customers into brand evangelists. Across all touchpoints and at all phases of the purchasing decision, you’re selling the brand, not just the product.

The consumer’s experience with your company at any given touchpoint is known as the brand experience. The total of interactions at various touchpoints over time results in a cumulative experience. Both individual and cumulative experiences matter. Chapter 10 discusses metrics in more detail, but it’s worth noting here that you will want to have mechanisms in place to gather data about your customer’s experience at each touchpoint.

As soon as you begin to communicate with the public, you should be striving for a consistent presentation of your brand across all possible touchpoints. Consistency applies to both the message content and tone, anywhere that your brand name or logo appears.

Positioning and Differentiation

Your brand position is the space in a given market that you occupy in the minds of consumers. It’s your unique niche. Customers mentally rank brands. How would you rank McDonald’s, Burger King, and Wendy’s? Understanding what is special about your product and what position it occupies in the market is a critical step toward gaining market share among your target audience. In the soft-drink market, 7UP was number three behind Coca-Cola and Pepsi. When it began to identify itself as the “UNCOLA,” it made itself the leader in a different category: alternatives to cola.

Positioning is a function of three elements: customers, competitors, and a characteristic. The customers are the target market you’re going after: whom are you trying to reach? The competitors are the other companies that are already in the market. The characteristic is your differentiator; in marketing, it’s called the point of difference. Early in the process of market research, you identified ways to differentiate your product from the competition: by features, price, or some other factor. A powerful point of difference for positioning your brand is something that’s both defensible (your competitors can’t quickly replicate it) and important to your target customer. As mentioned above: you can’t be all things to all people. Specificity is key.

Marketing expert Geoffrey Moore has a template for synthesizing a thorough positioning statement in his book Crossing the Chasm (HarperBusiness):

For (target customer) who (statement of the need or opportunity), the (product name) is a (product category) that (statement of key benefit—that is, compelling reason to buy). Unlike (primary competitive alternative), our product (statement of primary differentiation).

This statement incorporates all of the different preproduct considerations we discussed in Chapter 2 into one sentence and synthesizes them into a single message. Chapter 10 returns to positioning and differentiation within the context of marketing. In the preproduct phase, an understanding of whom you are building for and what position you wish to occupy in the market will provide you with a framework against which to make product decisions.

Brand development is an ongoing process, and it’s worth your time. If you create a brand synonymous with quality and a joyful experience, the resulting loyalty and satisfaction will translate to increased customer retention…and increased revenue. Recognizing the importance of branding to the overall success of the company, some startups make their first in-house hires early. For example, Nest’s third employee was sales and marketing expert Erik Charlton (see how Nest built its brand right from the start in “Nest Branding: A Case Study”).

Other startups hire a branding agency. Regardless of the approach you choose, it’s important to begin thinking about branding as early as possible. From the minute you exit stealth mode and the public becomes aware of your existence, consumers—as well as potential hires, partners, and investors!—are forming a perception of who you are. The more actively and thoughtfully you shape that perception, the greater your chance of becoming a successful company.

Now that you’ve found your team, identified your customers, targeted your market, and begun to formulate your brand, it’s finally time to start building the prototype.

Get The Hardware Startup now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.