I think of my photographic collection as a living thing—a body of work, if you will. It’s constantly growing, maturing, and evolving. As the keeper of this collection, I need to provide a suitable environment, one that takes into account the different elements that make up the digital photography ecosystem. If I do not manage and groom my collection, it may grow out of control, or even worse, images may be deleted, lost or stolen.

The Digital Photography Ecosystem

What Is Digital Asset Management?

The Prime Directive, and Other Goals

The Benefits of Sound Digital Asset Management

Exploring Digital Asset Management Tools

Rules of Sound Digital Asset Management

Understanding the Data Lifecycle

Intelligent Imaging Technologies

An ecosystem is made up of many parts that must not only coexist, but also work with each other to survive. When all the elements work in concert, the system can thrive. In the digital photography ecosystem, elements such file formats, metadata, computer hardware, software, and most importantly you—the catalyst that breathes life into the system—must all work together. We’ll need to get an understanding of how all the parts relate if we’re going to create a sustainable digital photography collection.

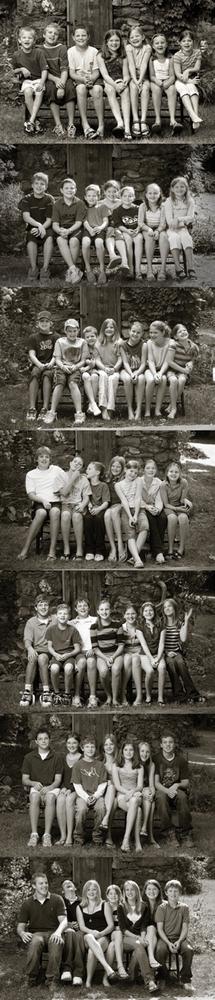

Beyond the technical details of digital photography is something more wondrous, however—the soul of the image—light, color, gesture, and the fleeting moment. And when all the souls of all the images can be brought together, something more wonderful still emerges. A photographic library can be far more than a collection of single image captures. It can represent a life’s work, or, indeed, a life lived (Figure 1-1).

And as we bring collections together, something even greater is formed, as complex and fascinating as the human mind. In fact, we’re in a period of profound and dramatic evolution of the photographic image. Our ability to bring multiple images together will change our perception of time, space, and point of view, just as the printed page, the photograph, radio, and television did in earlier times. Your collection is important to you for personal or professional reasons, but that’s not its only value. Digital photography is producing an extraordinary record of the history of our world.

Throughout this book, we’ll look at our images in terms of lifecycle, with an eye toward the elements of the ecosystem. How do we handle the newborn images, develop them to their fullest potential, and ensure a productive and secure life in maturity? How can we know when to replace elements of the system, and how can we accomplish this? Most importantly, how can we thrive and grow along with our digital photography collection?

Digital asset management—DAM—is a term that refers to your entire digital photography ecosystem and how you work with it. It comprises the choices you make about every component of your digital photography practice, including:

The images. The photos are the life-form that the system needs to support.

Software. The software you use helps to manage everything you do to the images. In order for the ecosystem to work properly, the software needs to support the tasks that are necessary.

File formats. Image data must be stored in a file type (or multiple file types). Your choice of file types has a big impact on the way you interact with your images and how you construct the rest of the system.

Organization. How do you know what your pictures are about? Which images go together? Which are the best? You can use various kinds of metadata to make your image collection easily navigable by you and by anyone who has an interest in it.

File storage architecture. How do you name your image files, and what kind of directory structure do you create to store them in? How do our concepts of storage and organization differ in the digital world?

Storage media. What kinds of hardware should you use to store your images, and how does that hardware interact with the other parts of the system?

Backups and validation. How do you protect against media failure, human error, or other hazards? How do you know that all the images are really there? How do you restore the archive after some kind of failure?

Workflow practices. How do you actually accomplish your goals as efficiently as possible? What can be automated, and what will you have to do manually? How can you configure a work order that maximizes security and efficiency?

Migration. Over the life of your collection, there will be times when you need to change storage media, organizational structure, file format, operating systems, or software. How do you make this transition smooth, while assuring that no data is lost in the process?

In this book, we will examine these elements largely in this order (with the exception of the images and the software, which are part of every stage), always keeping in mind that each component is impacted by the others. None stands by itself, so it’s important to think of the system as a set of interlocking parts.

In the book, I will deal with each of the components in two ways: I’ll outline the important technical underpinnings so that you can make informed choices, and then I’ll show you different options for managing the processes, including sample workflows. In most cases, I’ll present a range of practices that can work for all photographers, from the enthusiast to the busy professional, and all the way up to someone managing complex multiuser libraries. I’ll also be presenting my own methods—the way I deal with an archive of more than 300,000 images.

As you come to better understand the elements of the digital photography ecosystem, you will be able to make it less about digital and more about photography. When you’re first learning some new process, you mostly “see” the tasks in front of you as a series of steps, rather than as a series of goals. When you’re cooking gumbo for the first time, you may sauté the onions because the recipe says to. After you cook it enough times, you sauté the onions because you want the gumbo to taste like sautéed onions. Ideally, you reach a point where you haven’t simply memorized the steps, but understand the parts and can visualize the outcome.

Photographers are an independent-minded bunch, and often bristle at being told what to do. Because managing your collection is so deeply linked to what you photograph and how you think, there will be many variations on how to put these recommendations into practice. It’s not my desire that everyone does it like I do—just that everyone has a better understanding of why they are doing things a particular way, and what the costs, benefits, and risks are.

As my friend Steve (Figure 1-2) constantly points out, it’s essential to visualize your goals as you begin any process, and building a DAM system is no exception. So right here at the beginning, let’s lay out some priorities for what we want to accomplish. You’ll notice a theme that runs through all these goals: protection of and access to the images.

I like to say that we are moving from an imperfect present to a more perfect future. The prime directive, to borrow a phrase from Star Trek, is to not lose the pictures along the way. My most important goal is to help you get to the future with your photographic collection intact. That primary goal influences everything that is written in this book. At times, you’ll need to make some choices between speed and security. My recommendation will generally be to opt for more protection, but I’ll lay out the options so you can make your own decisions.

While preserving images is the main goal, it’s not the only important one; you need to be able to find images when you want them. If you can’t find an image, you can’t use it, no matter how thoroughly it has been backed up. And the organizational tools need to be intuitive to use and flexible enough to work for the way you shoot and the way you think. There are a lot of options available, and we’ll look at many of them.

A good DAM system will reduce your time in front of the computer. When you understand how all the tools fit together, it’s easier to use them at maximum efficiency. We’ll look at ways to automate the workflow where possible and also see where it would be dangerous to cut corners.

The most exciting new developments in imaging are seen in the nondestructive editing tools in programs like Lightroom, Aperture, Capture One, and others. While we won’t be talking much about how to pull the adjustment levers (there are a lot of other books devoted to that subject), we will talk a lot about the technology behind this kind of image adjustment. Most important, we’ll talk about how to ensure that the renderings you create are attached to your images in a forward-compatible way.

One of the most important goals for our photography collection is forward compatibility: the ability to move the images and the work you’ve done to them into the future. If you’ve been working with computers for 10 years or longer, you almost certainly have some computer files in your possession that you can’t open. You may no longer have access to a device that can read those Zip disks, or the program that made the files may have disappeared. We’ll look at how you can configure storage media and formats for forward compatibility.

It’s very intuitive to think of your image collection as being “in” a piece of software, but I think it’s important to understand it a different way. The software that you use to view and organize your collection is really pointing to a set of files and showing you information about the images. While I may do my organizational work in a particular software environment, the images and, hopefully, the organizational work I do, should be able to live independently of the software I’m using at the present time.

The tools that I will suggest in this book—in particular, the DNG file format and embedded metadata—let you create work that is largely software-independent at its very core. The image adjustments and the organizational work can be pushed back into the collection and can live there, even if you no longer use the software that you used to do the work. This is the best way to achieve forward compatibility—not just of the images themselves, but of all the important work you do to the images.

One of the most vexing issues with digital management is certainty. It’s something we take for granted in the physical world, where we can hold something in our hands and say, “Here is this thing.” In the digital world, this can be a much trickier issue. You can see “it” in your directory structure, but is it really there? Maybe not. And once you come upon uncertainty, it throws open the door to double-and triple-checking—frustrated, time-wasting flailing as you churn through your archive thinking, “Is this really happening to me?” I know—I have disappeared down the rabbit-hole of data loss and uncertainty more than once, chasing down the explanation as to why this file is corrupted, or are these really all the pictures of Maddy, or is there something wrong with this drive (Figure 1-3)?

In fact, I have found uncertainty to be one of the major time wasters in the digital world, and much of the research and development in this book has been part of a quest for certainty. Is it possible to know that my images have file integrity without opening each one in Photoshop? Can I know that my backups have been created and that I’m protected in the event of fire, theft, or virus? Can I find what I need when I need it? The answer, I can report, is yes; you can have a very high degree of certainty, once you understand the parts of the ecosystem.

Whether you are a professional photographer or an avid amateur photographer, you invest in the creation of your images, and you want to get a return. That return may be in the form of monetary payment or personal satisfaction. Either way, setting up a solid DAM system will greatly improve the return on your investment.

While creating a comprehensive DAM system may seem daunting at first, it’s really no more work than using a cobbled-together system. I’ve actually found that it’s a lot less work once you get everything streamlined. The benefits of your DAM system include aiding your productivity, adding value to your photos, ensuring longevity of your work, increasing your profitability, and allowing you to adapt to the changing technological landscape.

Digital photography has caused an explosion in the number of photographs that people take and have to process and keep track of. At the inception of the digital revolution, it was commonplace for digital editing tasks to take much longer to accomplish than their analog-world counterparts. Changes in imaging software have now made it possible for digital imaging to take far less time than film workflow did.

Cataloging software aids productivity by letting you easily create and make use of different kinds of information about your pictures. Because you can save this information and come back to it in the future, you can add organization to your collection as you work. For instance, you can combine assessments you have made about the quality of your images (ratings) with content information you have assigned to those images (keywords, for example) to find your best photos of any particular subject matter at any point in the future.

Consider for a moment the Bettmann Archive, the famous collection of images from the middle 20th century. Much of that collection was composed of images discarded from publishing houses—images considered valueless at the time. By systematically organizing these images, Otto Bettmann was able to turn them into a highly valuable collection of photographs and other commercial art. Corbis purchased this collection of “discarded” images for millions of dollars in 1995. Let’s think about that.

A photograph at the bottom of a landfill and one in the Bettmann files may each have the same artistic and intrinsic value. One, however, has a vastly greater market value. The difference is one of accessibility and organization—properties that are dependent on the images being part of a larger collection, and upon the existence of searchable classifications within that collection.

The market value of a photograph is dependent on your ability to get that image into the hands of someone who wants it. Digital asset management practices give you the ability to sort and retrieve photographs according to many different needs, and therefore to make the pictures more accessible.

All of the work that you do to rate and group your images will add value to them by making them easier to find and bring to market. Because DAM software lets you easily assign and leverage the work of rating and grouping your images, it expedites that process and creates value.

In addition to market value, good DAM practices will let you to get the maximum personal or artistic value out of your photographs. Digital photography, coupled with good DAM techniques, lets you find and work with your photographs much more easily (and enjoy them more) than you ever could have when working with film. In fact, for much of the work I do with my photography collection, I am the client, and the value that I strive for is personal value, rather than market value. Keep that in mind as you read through the workflow solutions offered here.

Picture editor Declan Haun used to say that you need to live with your pictures. An efficient DAM system lets you live with the pictures in ways that were hard to conceive of a few short years ago. Sitting on a plane as I write this, I’m but a few clicks away from catalogs that show every digital photograph I’ve ever made. This allows me to put images together in all kinds of useful ways (Figure 1-4).

Good digital asset management is essential to the long-term well being of your archive. It will help you maintain the completeness of your picture collection and it will be invaluable when it comes time to migrate your pictures from one system/media/format to another.

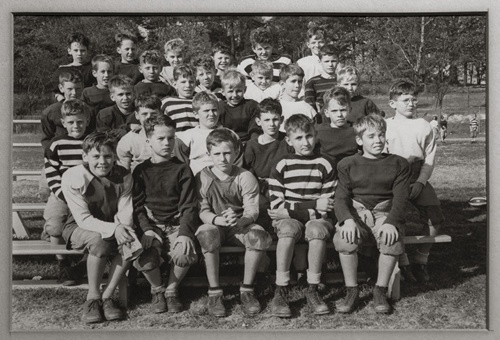

The most basic part of DAM practice, the storage and backup of image files, is obviously integral to the long-term survival of your photography collection. Figure 1-5 shows a photograph of my father on his fourth-grade football team (third row back, in the striped shirt). Sitting in the front row is his good friend Leonard Steuart, also in a striped shirt. Later in this chapter you’ll see some images created by Leonard’s son, Skip. What goes around comes around, and it’s nice to have the photos to prove it.

It’s essential that you have a simple, redundant structure for your photographs so that you don’t lose files due to any of the ever-present threats of theft, fire, media failure, computer error, lightning strike, computer virus, or human error. If your images are stored in an orderly manner and are well-cataloged, you will be able to recover from these hazards with a minimum of loss and hassle.

This section is intended to put a DAM system in perspective for independent professional photographers. If you don’t do this kind of work, you can skip ahead to the next section.

Many professional photographers have found that the fairest and most profitable way to “sell” images to clients is through the licensing model. This allows photographers to charge more for images that the client will get high-value usage from, and to charge less for images that have a lower usage value. In fact, the licensing model is entirely responsible for the creation of the stock photography market.

It is clear that the licensing model is the driving force behind the information economy. If everyone who bought a book could copy and resell it, there would be no profit in publishing books. For most intellectual property, from editorial publications (such as magazines) to products like software and movies, the revenue models rely on the multiple licensing of the same material. Look at Bill Gates, a multibillionaire. He has started two companies in his life: one, Microsoft, writes and licenses software; the other, Corbis, aggregates the rights to license photographs.

For photographers to economically thrive in a licensing-based economy, I suggest following a strategy that allows you to take part in the relicensing process, and hence share in the revenue stream. If you choose to follow this path, DAM will play a critical role in your own well-being, just as it plays a critical role in your clients’ businesses. It’s up to photographers to understand these challenges, to structure internal tools to deal with these challenges, and to help clients implement systems that work in everyone’s favor.

Note

As the sources of photography, we must integrate effective DAM practices into our workflows from the very start. We need to first understand DAM, then practice it ourselves, and then help our clients with it. The practices outlined in this book will help with all three of these tasks. And when you are in the position of offering valuable solutions—even ones that raise the price of your invoices to your clients—you become more valuable to those clients. As you read here about how good DAM practices can help you find images and track licenses, keep in mind that these disciplines will add value for your customers (and can make you money).

Let’s look at this from the photo buyer’s perspective for a minute. While it’s difficult for individual photographers to manage their images, it can get even harder for companies that acquire photographs. Images may come in with multiple naming conventions (or no renaming at all), and with metadata in various stages of completeness (or none at all) and done to different standards (or to no apparent standard). Files may be in many different formats, prepared according to each photographer’s preferences. Licensing agreements, model releases, and usage histories are among the external documents that need to be tracked with these images. It’s quite a challenge.

To effectively work with an institution’s photo collection, the photo manager needs to understand the DAM ecosystem even better than the individual photographer does. You’ll need to provide submission specifications, and in some case, that may mean advising the photographer on which software to use and how to accomplish the needed goals. You’ll need to create submission policies that allow incoming images to integrate with the collection. You’ll need to establish policies on file naming, keywording, job tracking, usage rights, and more. Understanding how this all fits together is essential. And you’ll need to really know the tools when images are submitted in nonstandard ways.

For a large number of institutional photo collection managers, configuring hardware may also be part of the job. Many institutional IT departments are unfamiliar with the issues related to media storage, and many of the existing systems are geared to preserving email and word-processing documents, rather than the much larger media files. I’ve helped a number of companies configure their own photo libraries because IT has been unable to create a system at a reasonable price. You’ll find a lot of help in this book, on many different levels.

You may not yet have thought about another challenge that will surely come your way: file migration. Eventually, you will likely need to move and/or change the format of all of your files because of the obsolescence of your chosen storage media, operating system, or file format. Of the three, your choice of storage media will generate the need for some sort of upgrade migration the most often (perhaps every two years). Chapter 12 deals with these challenges in more detail, but let’s get an overview now:

Storage media. As new technologies for file storage emerge, it will make sense to move all your files onto the new media (sometimes merely onto bigger drives). This will be desirable due to decreased cost, increased speed, increased capacity, increased reliability, or some combination of the four. If your archive is well-organized, this process can be almost entirely painless.

Operating system. Migrating a well-organized collection onto a new OS should also prove to be relatively painless. Transferring the files should be no big deal; the biggest potential hurdle here is making sure that you can port all of your sorting work to your new operating system and cataloging software.

File format. Migrating your collection to a new file format may be one of the trickiest operations. You will most likely need to do this because you have switched to a DNG workflow due to the advantages it offers in a parametric editing environment. I recently did this for my oldest legacy raw files, and it was a reasonably smooth, but labor-intensive, operation.

In the first part of this chapter, we put some context around the management of your images. Now it’s time to take a look at some of the tools we’ll be using to accomplish our goals. We’ll start by looking at the classes of software, and what each can do for us.

DAM software helps you sort, track, back up, convert, and archive your photographs. Its function is to store, view, control, and manipulate all the information you have collected about your photos, as well as the photos themselves.

Over the life of your collection, you may end up using several different DAM applications, either sequentially or concurrently. For example, you might use Adobe Bridge or PhotoMechanic to do initial sorting of your photos, but do your main, permanent cataloging in Microsoft Expression Media, idImager, or an enterprise-level application such as MediaBeacon. And some years down the line, you may switch to another software package entirely to administer your catalog. It’s important to remember that it is the information about your photographs, not the software you use or the catalog document itself, that is of real value.

There are several classes of software you may use to manage and work with your images. In fact, the lines between these classes of software are blurry, as one application may have some features of the other classes.

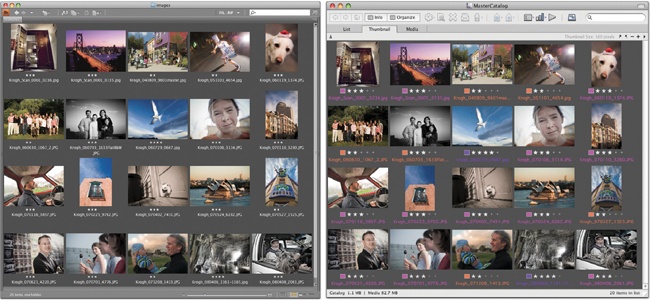

There are two fundamental kinds of software you might use to work with large groups of images—browsers and cataloging software. A browser is a piece of software that can display the contents of a folder or drive for inspection. It will have some organizing tools, but does not have the ability to remember what is in the collection when it’s not connected to the storage media. Cataloging software harvests a thumbnail or preview of the images, as well as the metadata, and keeps it in a database. It will have robust tools to create and manipulate metadata to organize and remember information about the images.

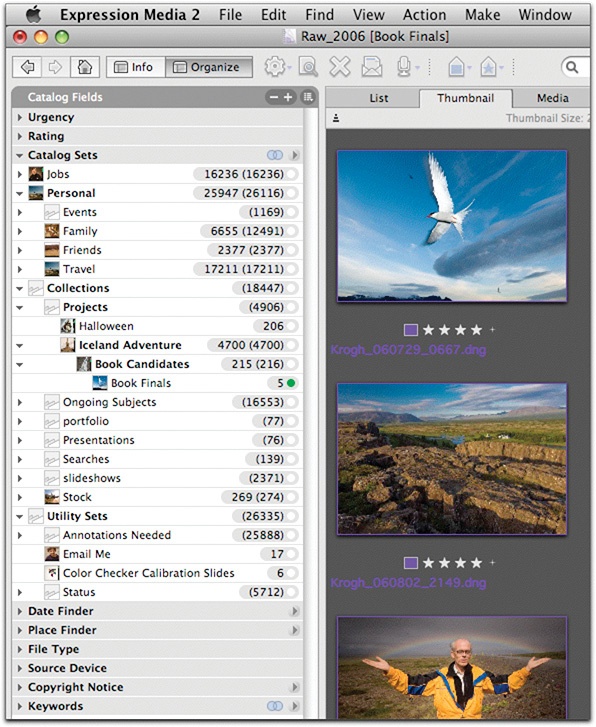

At first, browser and cataloging applications look similar. Each one can display multiple files, sort according to multiple criteria, and hand files off to other programs. Behind the scenes, however, there is an important difference. A browser extracts data from the files on a more or less “real-time” basis and builds its utility around this information. The image on the left of Figure 1-6 shows a typical browser screen from Adobe Bridge. Cataloging software, however, keeps a permanent catalog of information about the images, including thumbnails, metadata and more. You can see a screenshot of one of my Expression Media catalogs on the right side of Figure 1-6 (right).

Figure 1-6. At first glance, there doesn’t seem to be much difference between a browser (such as Bridge, on the left) and a catalog application (such as Expression Media 2, on the right).

Why is this difference between browser and cataloging applications important? Because cataloging software keeps the extracted information in a database, it has several important advantages over a browser. The differences between the application types don’t really become apparent until you have a large number of files to work with.

It’s DAM faster. One thing cataloging software can do better than a browser is to return search results quickly. Because cataloging software keeps all the organizational information in a database document, it only needs to do a local search to find, for instance, all images with “Josie” written in the keywords. A browser may have to look through the keywords of 100,000 files stored on several different drives to return the same results.

It allows collection-wide filtering. Because cataloging software can harvest and contain so much information, it allows you to organize images with much more flexibility. Since all the date information from a large group of images can be collected in one place, it’s easy to filter down to images only from a particular time frame to find just what you’re looking for. And you can easily use the shoot-date information combined with location information to find images from a certain time and place. Collection-wide filtering is powerful, and we’ll look at many different kinds of metadata that you can use to find small sets within your collection in Chapter 3.

It allows virtual sets. Even more important than filtering is the ability of good cataloging software to create and keep virtual sets. Virtual sets are like folders that you keep images in, except that you create them by pointing to the original files, rather than by moving the files into folders. This allows you to include an image as part of multiple sets without having to copy the file multiple times—for instance, the same file can live in the “Vacation” group, the “Grand Canyon” group, the “Pictures of Maddy” group, the “Stock Photos” group, and the “Mom’s Favorites” group.

Virtual sets let you create groups with specific intent, which is more valuable than simple filtering. While it’s useful to filter ratings against keywords to find, say, your best architecture photos, it’s even more valuable to select specific images for your architecture portfolio and save that grouping. This group, created with specific intent, has significantly more value than the filtered group because you’ve put more work into the selection process. You’ll want to return to it and know that it won’t change unless you tell it to.

The best of the cataloging applications will also let you organize your groups into nested subgroups (see Figure 1-7). For example, within the Collections group, you can create a subset called “Projects,” and within that you can create the “Iceland Adventure” group. This set of images can, in turn, be subdivided into “Book Candidates,” which can be further refined to the “Book Finals” group. I call these nested virtual sets, and I think they’re essential to organizing your image files. One reason is that they let you organize your collection according to what you shoot and the way you think. You can even subdivide the collection in many different ways—for example, dividing images into assignments in one nested hierarchy and dividing by subject matter in another. Nested virtual sets also help to reduce the visual clutter that organization can create. In my catalogs, I use several top-level hierarchies to help wrangle all the organizational terms.

It knows where stuff is supposed to be. Another critical advantage of cataloging software is that it knows where files are supposed to be, so it can assist you in keeping track of images that you may have erased, renamed, or moved accidentally. A cataloging application will be able to tell you that an image is missing and should be found or restored from your backup, while a browser will simply omit the file. Cataloging software therefore helps you to truly manage your files.

It allows faster backup of important organizational work. Cataloging software allows you to back up your valuable sorting work quickly and thoroughly. Because the cataloging application stores all the information you use to organize your collection in one place (the catalog), it is easy to back up your work after every sorting session. If you are using a browser to do sorting work, you will need to write a sorting term—a keyword, for instance—back into the original files. You may then have a bunch of widely distributed metadata that you need to back up if you want to be sure that you are saving this work. This adds quite a bit of time and complexity to the process of saving your work compared to simply saving the catalog document. We’ll see in Chapter 6 how you can use this saved catalog to restore the work in the event that you have to restore the archive from backups.

It allows you to work with offline images. Finally, cataloging software can work with offline image files, such as images at a different location, or photos that are on disks that are not currently connected to your computer. This offline capability lets you, for instance, copy your catalog to your laptop and take it with you on a trip in order to either work on it or show it to other people. If I am traveling and expect to have some downtime in airports along the way, I often use this opportunity to catch up on my image organization without having to bring the actual files with me.

Cataloging software has a lot going for it, but don’t take this to mean that a browser is not valuable. There are definitely times when you’ll want to see what’s in a folder or run some batch processes, and the best way to do that will be to use a browser to do the work.

Adjustment software can be divided into two main types:

Parametric Image Editing software (or PIEware) does its work by reinterpreting an original file, rather than by actually changing the original. All the changes to the files are stored in metadata. We’ll take an extended look at this in Chapter 2.

A raster image editor, like Photoshop, has many capabilities to do nondestructive image editing (through adjustment layers, for instance), but it will always alter the file itself.

Note

Those of us in the development community have been struggling for years to agree on a term for the kind of nondestructive image editing done to camera raw files. The term that has gotten the most traction is Parametric Image Editing, meaning that the parameters for image rendering have been altered, not the image itself. For the purposes of this book, I’ve shortened it to PIEware, although I often say the full name when I’m talking about this kind of software.

In the last few years, the software landscape for imaging tools has been revolutionized by the emergence of cataloging programs that include a way to do nondestructive image editing—cataloging PIEware. Adobe Lightroom and Apple’s Aperture are two examples of programs that can manage an archive as well as make the pictures look the way you want them to. This approach will eventually provide the best possible way to manage an archive, but the current versions of the software may not provide everything you need yet.

While the image editors in these cataloging all-in-one applications are as good as any PIEware out there, the catalog capabilities are not as robust as the dedicated catalog software (at least as of this writing). Building a good catalog program is surprisingly difficult, and it’s made doubly hard when the developers are incorporating a parametric image editor into the mix. It’s clear in both Lightroom and Aperture that some very significant catalog capabilities are simply not built yet. These omissions include working with the video files that come out of many digital cameras, flexible organizational tools, and multicomputer capabilities. They also don’t currently have the ability to open multiple catalogs at the same time, nor to search for missing files on a collection-wide basis.

If you can do everything you need to with an all-in-one application, your life can be considerably simpler than creating a multiapplication workflow. A person with one “photography” computer whose images can fit into a single catalog can probably do everything inside of Lightroom or Aperture and would be well-advised to do so (depending on what other needs he might have).

Once you start adding more computers to the mix, or more than one user, or more than one drive for storage, or more than one catalog of images, these programs start to break from a workflow perspective. I suggest it’s better to use a dedicated cataloging program to organize and manage the collection as a whole, even if you still use your cataloging PIEware to manage large groups of images as they are works in progress.

Remember the prime directive here. We’re moving from an imperfect present to a more perfect future, and we want to bring the images along for the ride.

There are various types of applications you may decide to use to enhance your DAM system:

Downloaders help with the ingestion process.

Backup software helps you manage the process of creating duplicate copies of the files. You can also use backup software to create a validated transfer of data so that you know the copy is an exact duplicate of the original.

Data validation software can help you determine that your archive is healthy by examining the media, the volume structure, or the files themselves.

System and disk utilities help to ensure the general health of your computer and the storage components. Like it or not, you need to pay attention to this stuff if you want to ensure the integrity of your archive.

Table 1-1 gives examples of the various types of software available at the time of this writing.

Table 1-1. Examples of DAM software

Type | Example |

|---|---|

Browsers | Adobe Bridge, PhotoMechanic, Google Picasa, ACDSee |

PIEware | Adobe Camera Raw, Capture 1, Bibble 4, Nikon Capture, Canon DPP |

Catalog Software | Expression Media (formerly iView MediaPro), Extensis Portfolio, idImager, iMatch (PC only) |

Catalog PIEware | Adobe Lightroom, Apple Aperture (Mac), Bibble 5 |

Downloaders | ImageIngester Pro, PhotoMechanic, Downloader Pro |

Data Validators | ImageVerifier (for image files), Adobe DNG Converter (if you use it right) |

System and Disk Utilities | System Mechanic (PC), TechTool, Disk Warrior (Mac) |

Backup Software | CrashPlan (cross-platform), Acronis True Image, Syncback (PC), Chronosync, SuperDuper!, Carbon Copy Cloner, Time Machine (Mac) |

Some of you will adopt the exact nuts and bolts of my system wholesale; for others, it will be important to adjust the system to reflect your different needs. In any case, there are fundamental principles at work that everyone can take advantage of:

One of the most common mistakes that photographers make when building digital archives is using a hodgepodge of DAM practices. Of course, your system will change over time as you get smarter about digital technology, as your tools change, and as your collection grows. It’s important, however, to bring work done under older protocols in line with your new techniques. If you leave lots of work organized in different ways, you won’t be able to leverage its value fully, and you risk being unable to ensure its integrity over time. My system will provide an excellent framework for the systematization of your DAM.

Humans have a wonderful ability both to remember and to forget. For example, although my kids are now 13 and 15, it seems long ago that they were infants. At that time, I felt like I would never forget the details of their early daily lives. Only a few years later, all those details are now a fuzzy half-memory.

I have had photographers tell me that they don’t need a DAM system because they can remember everything: the entire contents of their collections, where all the pictures are stored, and what each version was created for. Realistically, though, not only are you unlikely to be able to remember all of the details (especially as your practice changes over time), but if you try to do so, you will be missing out on many of the benefits that a catalog-driven DAM system offers.

The content information that is collected about photographs in a DAM catalog can be useful for many things and to many people. It can help you find photos efficiently when you want them. It can help your clients conform to their licenses and it can help to automate the marketing and distribution of images. It can also help family, friends, or business associates locate and identify pictures if you’re not around to help.

The more universal your cataloging structures and practices are, the more value and efficiency you can get from your images (DAM systems have a particular ability to add value to a collection as a whole). Consistency in organization allows for faster and more reliable searching of your collection, and collecting related images together maximizes the value of each individual image. A collection of visionary landscapes, for instance, has a greater value than an equally visionary collection of images that do not share a subject or any stylistic elements.

The most obvious ramifications of this principle have to do with storage, longevity, and scalability. Computers have been around long enough now that the challenges related to storage media are pretty well-known. We know that we will have to migrate our files eventually, and that storage media can fail. We also can see that the amount of storage we will need will grow exponentially over time. It’s important that a system be able to grow orders of magnitude larger without having to be completely restructured.

Here’s where DAM can actually start aiding productivity immediately. It starts when you rate the files for quality and annotate them for content. By allowing you to quickly filter down to just the best and most appropriate images, DAM immediately streamlines the image preparation workflow.

Every time you identify characteristics of your images—from quality to content to usage—you add value. If you use integrated DAM tools to do this organizational work, you can save and reuse the valuable information that you have recorded.

Think of the times that you have sorted physical photos for one reason or another. Once you re-sort those images, all of your prior sorting work is lost. DAM cataloging software, however, lets you sort into virtual sets, so you can save a nearly infinite number of groupings of images. By using these virtual sets, you save search time and add value to your entire collection.

Once you see the control that good management gives you over your collection, you might find yourself going “DAM happy.” You need to strike a balance between what’s useful and what’s a waste of time. Noting who is in a photo is very useful; labeling each image “looking right” “looking center” or “looking left” is probably overkill. The methodology I present starts with the tasks that offer the highest return for your work, and gradually works down through less cost-effective tasks.

One of the most helpful concepts that you can bring to your DAM system is an appreciation of the data lifecycle. I’ve split this into three parts that represent different phases of the image’s life. Each one carries with it tasks and hazards that are unique to that period. Using these distinctions can help make the system manageable.

I’ll be referring to these phases throughout the book. Let’s now take a look at the phases, and see what’s unique about each.

Ingestion is the start of life of your images—the first transfer from the camera to the computer. Two kinds of challenges are unique to the ingestion phase. The first is that there is only one copy of the image file, so it’s pretty vulnerable to corruption or loss. The second challenge is that a number of processing chores are best done at this stage. The ingestion stage is an important opportunity to use computers for what they do best—performing repetitive tasks quickly and reliably without a lot of user involvement. We’ll take an extended look at this in Chapter 7.

Tasks for ingestion include the following: renaming, adding bulk metadata, adding rendering settings, backing up, DNG conversion, sending to image editor, and preparing for visual inspection.

We’ll see in Chapter 7 how you can automate nearly the entire process.

I use the term working files to describe images that have gone through the batch processes that are part of the ingestion phase but have not yet gotten to the safety of the archive phase. In this stage, you will generally want to do image preparation processes that make the images ready for the archive (as outlined below). Working files are in a state of rapid change, and are best handled by a different backup protocol, which is one of the reasons that it’s helpful to think of them differently than either the ingestion or archive phase.

Working files tasks include the following: rating for quality; basic grouping; image adjustment; proofing output; multi-image proof-stitching (panoramas and HDR, for example); preparation for archive (folder finalization, DNG conversion if needed); derivative file preparation, as needed; and validated transfer to archive.

Note

One of the great advantages of using a cataloging application that is also a parametric image editor is that it can drastically shorten the time that your original files are works in progress. Since all the changes you make to your images (both metadata additions and image adjustments) can be saved in the catalog database, there are very few things that you will have to do with the images between ingestion and archive. As long as the images have their permanent names, any work you do to the files can be saved in the database and reattached to the images later in the event you have to restore the archive from backup. We’ll outline this more thoroughly in Chapter 6 and Chapter 9.

I use the term archive files for any files that have been put in their permanent homes and safely backed up in a secure, long-term way. In my studio, many original files are archived long before I have actually delivered the final derivative files.

Since the archive is the safe and permanent home for the photos, the goal is to move the images into the archive as quickly as is practical. We’ll take an in-depth look at how to structure the archive in the coming chapters.

The creation of derivative files complicates the neat arrangement of the originals archive. Images get reworked at later dates (sometimes much later), and this messes up the backup arrangements that are so clean and easy with a single original archive. These files are high-value images, however, and need to be protected as much or more than any other image. (As a matter of fact, they are likely to be your most valuable images.) Later, I’ll outline how you can archive originals and derivatives separately so that you make the archive process as simple and secure as possible.

Archive tasks include backing up to a second hard drive; backing up to an additional media type; proofing, as needed; sending files back to the working files folder for reworking, as needed; and periodic data validation.

There are some pretty remarkable technologies emerging with respect to image collections. Some of these center around imaging itself, and some are related to new ways to automatically tag images. In both cases, these technologies change the way we can think about groups of images and how we interact with them. Let’s take a look at some recent developments in the world of imaging.

As the tools of photographic imaging change, our ability to create and understand different kinds of imaging evolves as well. This is a constant process in many art forms—think of the evolution of jazz, rock and roll, and hip-hop. As both the artists and the audience become familiar with new styles, it’s possible to take the art form in remarkably innovative directions, sometimes to places that would be incomprehensible to those who had not been following along. It’s clear that we are in the middle of the development of a new visual intelligence in imaging, one that alters and combines images into entirely new forms.

This new field is called computational imaging. Computational imaging is a subset of digital imaging in which the resulting image could only be created by computers, often by combining multiple images together to form a new whole.

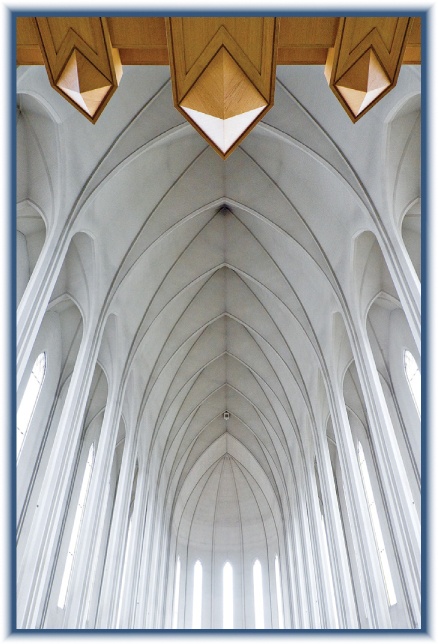

One example of computational imaging is high dynamic range, or HDR, images. In an HDR image, several photos with different exposure settings are combined to create a new image with lots more steps between black and white—an extended dynamic range. This lets you capture deep shadows and bright highlights that would be lost in a normal digital photograph (Figure 1-9).

Figure 1-9. With an HDR image, multiple images can be combined to create one with an extended dynamic range.

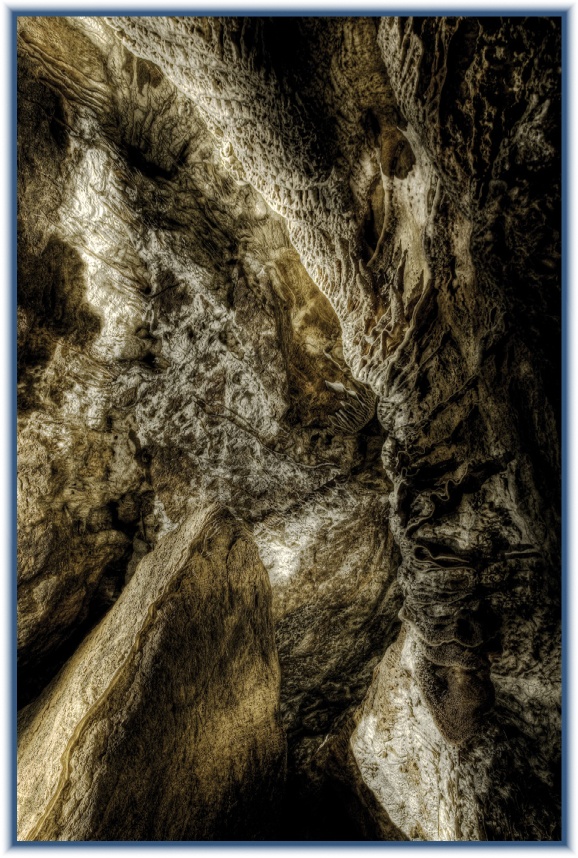

An HDR image can also be processed to look more like an illustration than a traditional photograph (Figure 1-10). This technique is an alternate way of mapping the tonal range of the image, making localized contrast corrections. Bright regions are darkened, and dark regions are lightened, mimicking the way the brain processes visual signals.

Figure 1-10. Some HDR images look like illustrations rather than photographs, because our concept of what a photograph looks like is so anchored to film-based imaging. As this technique becomes more widespread, more people will see these images as photos, rather than illustrations.

Multiple photographs can be stitched together create wider fields of view, more resolution, or more depth of field than can be achieved by a single exposure. While panoramas have been around since the very early days of photography, we’re starting to see uses of panorama stitching that are not straightforward re-creations of film panoramas (Figure 1-11).

Figure 1-11. In this panorama stitch, the framing is haphazard, and the timeframe is imprecise. The effect is an image that provides a more multidimensional representation of the event. Not only is the third dimension represented, but the fourth—time—is also part of the image.

HDR and panoramic images are simple things compared to other kinds of computational imaging that are being developed. The Flexify plug-in for Photoshop can provide new kinds of representations of three-dimensional space, as shown in Figure 1-12 and Figure 1-13. Microsoft’s Photosynth has the ability to take thousands of photographs shot by different people and use them to reconstruct a three-dimensional representation of a space—a point-cloud—and let the user navigate around inside the image (Figure 1-14). These are early examples—there’s no limit to where this kind of thinking can go. For instance, movies could be incorporated into this technology, as well as use of timestamps on photographs, to make it a truly four-dimensional record.

Figure 1-12. Here’s a stitched panorama of the Google campus that is also an HDR image (made by my friend Skip Steuart). It took more than 50 indidivual frames to create this image.

Figure 1-13. We will increasingly start to see alternate representations of three-dimensional space. Here’s what the Flexify plug-in does to the panorama.

One of the most common features of all these new imaging developments is the use of multiple images to create a new kind of image. This poses a challenge and an opportunity for the photographic collection. The images must be preserved so that they’ll be available when the new technologies arrive, they must be accessible, and it must be possible to find them and bring them together into the new tools. A collection that is well-managed and well-annotated will be able to take advantage of new imaging tools in ways that we can’t even conceive of now.

You may not believe it, but the last thing I want to spend my time doing is adding keywords to my photos. While it’s true that I’d like my photos to be easily found in my collection, it’s also true that I don’t particularly like to do the work to make them findable. You’ll see a number of tools in this book to help ease the work of tagging the images. Some, like bulk metadata tagging, require some work, but can be applied to lots of images quickly. We’ll also look at some automatic tagging, such as the date-tagging that your camera does, or GPS tagging that can be done with a saved tracklog.

But how about all that cool new stuff—face recognition in iPhoto and more? Can’t it just know what my pictures are about and add the information? While this technology is improving, it’s important to think about the limitations of this technology and, more importantly, what we can do to increase our access to new tools as they become available. Face recognition, for instance, needs to have a good set of sample images to work from. If you have created tags for the important people in your collection, it will be much easier to train the new technology to find other instances of those people. And if a person is not tagged at all, he or she is much more likely to remain hidden in the collection.

The bulk tags that you apply to your collection will make autotagging functions much easier. If you have images from family vacation tagged as “family,” the face recognition application can work more efficiently to find individuals. This goes for all the bulk metadata you create: dates, events, location, client names, and, yes, the names of those pictured.

And finally, sometimes it just makes more sense to take a few seconds to add data than to rely on some future high-horsepower application to do it later. If you’ve spent hours shooting someone and have an entire shoot with just one person pictured, take a few seconds to embed the name of the subject into the metadata for the images.

Yes, sometimes I’m exhausted from dealing with all this digital stuff, but that’s not what I’m talking about. One of the most promising areas of autotagging comes by making use of your own personal digital exhaust. By that, I mean the trail of data that is left behind from your computer, phone, and PDA. It’s becoming possible to use this stuff to do some image tagging. At the moment, the easiest place to see that is with the iPhone, which can record GPS data for photos you shoot with it. These photos, in turn, can be used to make a tracklog that you can mash up with the images made by a digital SLR to tag them with the location where they were taken (more on GPS and tracklogs in Chapter 3). It’s not a stretch to imagine that your calendar could also be used to tag event names, or that phone lists could also be of use.

I’ve seen a number of these new technologies in beta form, and I’m excited about what’s just around the corner. Even as we know new treats are coming, let’s make sure to keep our eye on the ball that’s here today—preserving our images, making them discoverable, getting the most out of them, and streamlining our workflow. As you move through the rest of the book, you’ll see how to make use of the great tools we already have.

Get The DAM Book, 2nd Edition now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.