Apple shipped Mac OS X Public Beta in September 2000. More than 100,000 people bought the beta, and Apple reported that there were more than 75,000 feedback submissions. Not only did the Public Beta serve to indicate that Apple was going to ship Mac OS X, it helped Apple identify the issues that users needed to have addressed in order to replace the original Mac OS.

After four years in development, the first full release of Mac OS X, known to the engineers who worked on it as Cheetah and to the public as Version 10.0, finally shipped on March 24, 2001—17 years and 3 months after the introduction of the original Macintosh. People gathered at stores everywhere to welcome its introduction. The fusion of Mac OS and Unix was complete, and Apple finally had the next-generation operating system that it wanted.

This release brought the following features:

- Carbon

A subset of the original Mac OS Toolbox APIs that could be safely transitioned from the old Mac OS to the new one, Carbon was the lifeline for older Mac OS applications, allowing them to be ported to the new system. This meant that applications essential for attracting users to the new system, such as Microsoft Office and Adobe Photoshop, could be ported to Mac OS X and take advantage of preemptive multitasking and protected memory.

- Quartz 2D

The powerful imaging layer of Mac OS X, Quartz 2D handles all the drawing on the system and delivers a rich imaging model based on PDF (replacing the Display PostScript used by NEXTSTEP), on-the-fly rendering, and anti-aliasing—all managed by ColorSync to ensure graphics look their best.

- Quartz Compositor

The windowing system for the OS and provider of low-level services such as event handling and cursor management, the Quartz Compositor is based on a “videomixer” model where every pixel on the screen can be shared among windows in real time. This model allows for smooth transitions between the states of a GUI; one of the traits of the Aqua experience.

- Aqua

More than a color, and more than something that brings to mind the properties of water, Aqua is an attitude. When Apple set out to design the interface for Mac OS X, it wanted to take all the good parts of the previous Macintosh and mix them with new features made possible by modern computer hardware.

Aqua brings the user interface to life with depth, transparency, translucence, and motion. Aqua also recognizes that it is managing a thoroughly multitasking machine. Instead of popping up dialog boxes in the middle of the screen, Aqua provides sheets that are attached to the window that they pertain to, allowing other tasks to be performed without hindrance and clearly communicating function to the user.

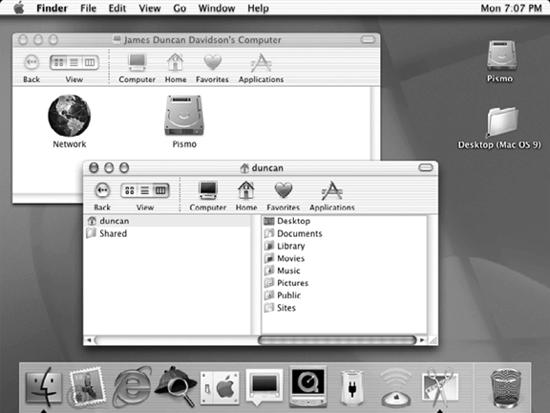

The Aqua interface is pictured in Figure 1-5.

An easy-to-use mail client, Mail was (and is) compatible with Internet-standard mail servers that use the SMTP, IMAP, and POP protocols, and it shipped with a built-in configuration to seamlessly access iTools-based http://Mac.com mail.

- iTunes and iMovie

Critical to Apple’s Digital Hub strategy, the first release of Mac OS X also included ports of the iTunes and iMovie applications, which first appeared on Mac OS 9.

Impressive as it was, by all measures, the first release of Mac OS X was not quite ready for most of the Mac faithful. It lacked DVD playback, and the major applications like Adobe Photoshop and Microsoft Office weren’t released yet. Still, it was more than usable for the Unix geeks, who were among the early adopters. Many improvements were to come, but Mac OS X’s first consumer release signaled that it would not be another failure like Copland.

As Mac OS X was developed, Apple made sure the open source foundations of Mac OS X remained open by starting up the Darwin project. Darwin is essentially the non-GUI part of Mac OS X and is a complete operating system in itself. If you are interested in running Darwin separately, you can download it for free from Apple’s Darwin site (http://developer.apple.com/darwin/) and have a full working operating system. It won’t have the Mac OS X Aqua desktop, but you can use Darwin just like you would Linux, from the command line and using the X11 window manager.

The main tree of Darwin is kept under pretty careful control; after all, Apple builds the base to an operating system that it distributes to millions of people from this tree. To provide a place for experimentation, Apple and the Internet Software Consortium run the OpenDarwin project . You can find the OpenDarwin site at http://www.opendarwin.org/.

When Apple released Mac OS X, they made a great decision by also deciding to provide development tools to every Mac user for free, including the Project Builder IDE and the Interface Builder GUI layout application . These aren’t just simplified tools to learn development with; they are the same tools that Apple uses to develop the operating system itself as well as its various applications. These tools allow development of Carbon - and Cocoa-based applications, system libraries, BSD command-line utilities, hardware device drivers, and even kernel extensions (known as KEXTs).

The developer tools aren’t installed by default, because Apple doesn’t think most users will want them and would probably want the almost 500 MB of disk space for something else. But developers, as well as power users who want to compile programs available in source code form on the Internet, can easily find them and install them from a variety of sources. And, since they are free, any user who wants to try developing software can do so purely by investing the time it takes to learn.

It is difficult to say what kind of success Mac OS X would enjoy without having access to the command line. According to legend, as Rhapsody developed into Mac OS X, there were many within Apple who didn’t want to ship the Terminal command-line

tool—or at the very least, wanted it installed only as part of the developer tools. After all, the command line was seen as the antithesis of the Mac experience. However, those who wanted the command line to be present prevailed, and the Terminal shipped in the /Applications/Utilities directory.

This was a fortunate move indeed, as a large percentage of the early adopters of Mac OS X were not traditional Mac OS users, but switchers from Linux and other flavors of Unix, including Solaris and FreeBSD . Without access to the command line, these users—a market to which many at Apple in 2000 probably didn’t expect to sell—would never have moved to the platform.

Get Running Mac OS X Tiger now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.