Chapter 1. The Conference Industry

We can’t talk about how to submit, create, and deliver great presentations without understanding the context in which those presentations will be given. There are many different event formats out there, with varying goals and business models.

Each conference is at a different place in its life cycle: some are exploring nascent subjects in the hopes of defining them, and others are reviewing well-worn material and focusing on practical applications of the subject matter.

Two Key Dimensions that Define a Conference

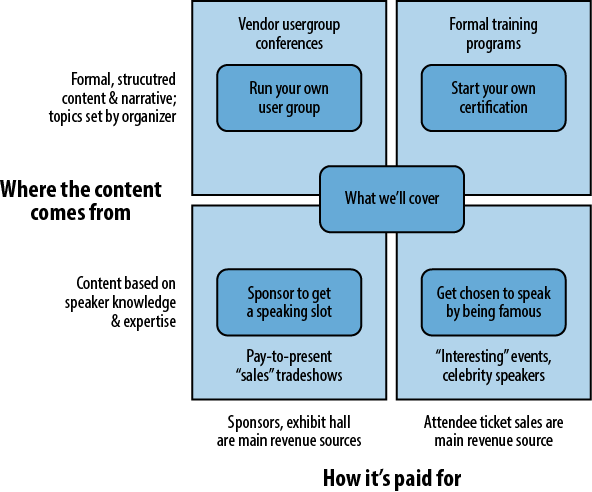

There are different kinds of events; it’s important to distinguish them. Two important dimensions to consider are where the content comes from and how the event is paid for, as shown in Figure 1-1. These concepts drive how speakers are selected and what the topics will be.

There are four basic conference types: vendor-run user groups, formal training programs, pay-to-present tradeshows, and pay-to-attend seminars.

These two dimensions are useful because they explain how the organizers think about their content:

A vendor user group conference generally involves end-user training and is run to maintain user loyalty, train users, and help ecosystem partners. Examples of this include Microsoft’s MIX conference, Dreamforce, Android Open, VMworld, and Oracle World. The majority of the funding comes from sponsors (and the company itself), and the schedule is decided largely by the organizers and thus reflects their agenda.

On the other hand, a pay-to-present “sales” tradeshow is paid for by sponsors, who get to speak about whatever they want. These events have little separation between content and money, so the stage is usually a series of presentations about each vendor’s offerings. Although the content might not be independent, the price is cheap because attendee tickets are usually free or easily available. The content may be driven more by partisan agenda than speaker expertise; nevertheless, such events can be a useful way to spread knowledge and collect leads.

A formal training program like the old Business Communications Review courses on WAN communications, or a CISSP security designation, are often subsidized by an employer and can get the attendee a higher salary or better job prospects. Executive MBAs also fit into this category.

Finally, the “interesting” events with celebrity speakers are attendee-paid, speaker-chosen conferences that lack formal structure. TED, The Lobby, Summitseries, and Web 2.0 Summit are good examples of this. Ticket prices are high, even to the point of creating prestige and exclusivity. The presenters are famous—or interesting—enough to speak on whatever they choose. Generally, there’s no submission process: speakers are found based on the personal networks of the organizers and alumni and newsworthy events.

In reality, every event is a blend of these—some free events have a sponsor who says a few words; some vendor user groups have an exhibit hall; some formal programs include “unconference” tracks with less structure alongside their more rigid schedule; and invite-only “interesting” events are more like speed dating than education, using scarcity and celebrity to drive up ticket prices and focusing as much on surprising experiences, networking, and extra-curricular activities as they do on content.

It’s also important to note that some conferences, particularly academic ones, don’t fall neatly into this model. Although presenters are chosen by peer review based on merit, there’s still a planning and judging process to understand.

The events that appeal most to for-profit companies are those with a reasonably structured format (so that topics they care about are covered) and with content for which an audience pays (because when ticket prices are higher, attendees tend to be higher-level employees and executives with signing authority).

These events fall somewhere in the middle of Figure 1-1. For this kind of event, organizers often have a theme and narrative in mind. There’s an advisory board, a formal call for papers, and a review process. O’Reilly Web 2.0 Expo, Strata, and Velocity are examples of this format, as are conferences like Interop and industry association events such as CMG and eMetrics. It’s this group of events I’ll be talking about in the rest of the document, though the lessons covered here are useful for any kind of public appearance at which you want to engage the audience and be remembered.

Note

Festival-format events like Mutek, Decibel, South by Southwest (SXSW), or the Edinburgh Fringe Festival are hybrid events at which speakers are a blend of those who submitted and those whom companies pay to sponsor the programs or surrounding events. If you’re submitting a proposal to them, then what you’ll read here should help.

Because these events have both executive-level audiences (with the authority to make purchases) and a specific topic or segment of an industry, it costs a lot to buy a sponsored speaking slot. Being chosen to speak, on the other hand, costs nothing. An investment in the right submission and the right presentation pays handsome returns. Furthermore, if your company is exhibiting at the event, interesting presentations contribute to better booth traffic and more leads.

Note

Conference veteran Bob Goyetche points out, “As conference planning becomes easier, there’s a whole movement of community-driven events (the *-camps, some *-fests, etc.) that feature very engaged participants not led by a vendor or platform. The possible returns of speaking at such events can be handsome as well.” Grassroots events, even those with little or no admission cost, tend to fit in the bottom-right corner of Figure 1-1.

The Life Cycle of an Event

All topics have a natural ebb and flow. Conferences and events happen because there’s information to share, but the kind of information that’s being shared depends on the life cycle of the event.

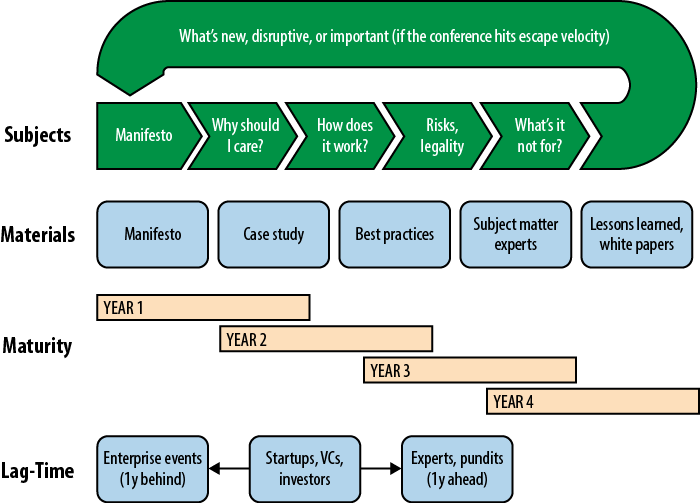

The best way to understand how an organizer is thinking about a conference is to look at the subjects that are discussed, the materials that are distributed, and the audiences that attend the event. Figure 1-2 shows these stages, along with the subjects covered and materials you’ll see.

A conference starts when an entirely new topic reaches critical mass. The pent-up interest in the subject grows until there’s a group willing to come together, either organically (as an “unconference”) or formally (within an industry or trade association such as the Web Analytics Association or the Computer Measurement Group). In technology, for example, this happened at the advent of mainframes (CMG), client-server computing (Interop), web protocols (Web 2.0 Expo), and cloud computing (Cloud Connect). But it’s true of any new subject.

Stage One: What Is It?

In the early days, much of the event is devoted to defining what things are, agreeing on terminology, and providing metaphors and connections to well-known models so that people can understand the subject. Whether this is a Tea Party campaign comparing fiscal policy to a tax on tea or a cry for increased scientific funding that recalls the Dark Ages, appeals to history are often useful.

The best presentations tend to look like James Burke’s Connections,[1] weaving history and speculation together into a whole and providing convenient metaphors with which to familiarize the subject. Nicholas Carr’s The Big Switch framed the discussion of cloud computing; Clay Shirky’s Here Comes Everybody and Don Tapscott’s Wikinomics did the same for enterprise collaboration.

In the early stages of a topic, branding is done with cool names and memorable logos.

Note

The Big Data industry, circa 2010, sounds like the cast of a comic book—Hadoop, Cassandra, Pig, Mongo, Basho. Proponents rally around technology stacks rather than applications or industries.

You’ll also see more manifestos and fewer white papers at this stage. Provocation and controversy are the lifeblood of the industry, with Big, Hairy, Audacious Goals[2] around which to gather supporters.

Note

At a 2007 hackathon, a friendly rivalry between Python and Rails developers devolved into a snowball fight that was a highlight of the event.

Stage Two: Why Should I Care?

Once there’s a reasonable understanding of a topic and the ley lines of discussion are in place, audiences start to ask why instead of what. They’re eager for practical applications and justifications because they need to decide whether to put the subject matter to work.

Instead of inflammatory manifestos and impassioned stump speeches, the discussion shifts to case studies and inside information on early adopters. It’s all about justifying a move and overcoming the inertia inherent in any industry. This is what Geoffrey Moore referred to as Crossing the Chasm.

This is also the point at which enterprise customers start to pay attention because business cases for something start to materialize. Whether it’s social media marketing, cloud computing, or how to flip real estate, once there’s a why, there’s a business discussion to be had.

Stage Three: How Does It Work?

Once the audience members know that the subject being covered is inevitable, they want to get their hands dirty. When social media was in its infancy, pundits opined on how it would transform our worlds. Later, marketers started to talk about the low barrier to entry, the return on investment (ROI) on social campaigns, and so on. But it took several years before they really wanted to understand how it functioned.

At this stage, workshops prevail. One thing organizers struggle with at this stage is the Paradox of Specifics[3]: audiences want concrete how-to information, but they don’t want to be sold to. That leaves presenters with only a few options:

Speak at a generic level. If you’re at a hospitality conference, talk about how to deal with guests, but leave out the names of brands or tools you use.

Speak about the industry giants. If there’s a clear leader in the industry, then it’s acceptable to discuss. Talking about search engine optimization? It’s okay to mention Google.

Speak about free products. If you’re at a conference on blogging, then teaching WordPress is fine, because people can use it for free.

Do an “industry survey.” Compare how different vendors solve a particular problem, or what salaries are like within the attendees’ professions.

This is a much bigger challenge to organizers than it might seem. Vendors want to showcase their product; audiences don’t want to be sold to; and organizers want to move the discussion on to practical matters. Independent analysts can often get away with mentioning products and vendors, provided that they aren’t seen as a shill for a particular offering.

Stage Four: Risks, Obstacles, and Legality

Now that the attendees know how something works, they want to know the challenges they’ll face. Running a conference on buying and flipping houses? It’s time to look at tax consequences, risks of mortgage defaults, and nightmare tenants. The audience is ready to start applying what they’ve learned in past years, but they want to mitigate as many of the common problems as possible by learning from others’ mistakes.

Case studies work well here, and for vendors, a little humility and wound-licking is in order. Did it take you a while to figure out the right solution? Did a customer implementation go horribly wrong? Did you spend millions of dollars trying to sell something in the wrong way? Explain that. It’s probably a better way to win hearts and minds than a product pitch.

Stage Five: What Can’t I Use It For?

In the final stage of an event life cycle, there’s a strange backlash. The pendulum of enthusiasm has swung too far in one direction, and now people want to find a healthy balance. Take cloud computing, for example: once audiences are convinced it’s the right thing to do with all of your IT, they’re fascinated by examples of what doesn’t work in a cloud.

This is a transitional phase, at which the subject of the conference is now mainstream and the old ways are now novel because they’re outliers.

Beyond: What’s New?

For many conferences or events, this is the end. There’s not enough “new” happening to create a critical mass around the subject matter. Everyone knows the subject, and they don’t want to rehash the same old topics. The event turns into an annual reunion, and excitement drops.

Smart conference organizers anticipate this in stages three and four and try to extend the life cycle:

They might branch out into new markets, such as recent graduates, those hoping for a career change, or international versions of the event.

They might divide the topic into more specialized segments (for example, a web analytics event could split into events focused on retailing, Software-as-a-Service, media, and CMS, allowing attendees to go deeper into each subject).

They might create adjacent businesses—webinars, book imprints, or consulting offerings.

They could organize regional events and membership groups, turning attendees into a community.

They could create formal certification programs.

They could align themselves with dominant vendors and become the user group event for a big firm with its own ecosystem.

Truly great conferences flourish because there’s enough activity within their industry each year to generate new discussion. If the event has reached escape velocity, audiences will return each year to keep abreast of topics in their field. This kind of event may repeat popular content year after year and likely has tracks devoted to innovations within the field. Organizers worry less about finding new attendees and sponsors and more about encouraging alumni to return. Feedback matters more and the attendees expect the organizers to chart their career path for them.

As you shall see, knowing where in this life cycle a particular conference is makes it possible to align a submission with the agenda that the organizers have for their event.

[1] If you haven’t watched Connections or The Day The Universe Changed yet, put this down and do so. It’s an amazing example of how to tell stories in interesting and unexpected ways. See http://bit.ly/YqgX3Y.

[3] Not a real paradox. But it sure makes it sound more important.

Get Propose, Prepare, Present now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.