When you first turn on a Mac that’s running Mac OS X 10.5, an Apple logo greets you, soon followed by an animated, rotating “Please wait” gear cursor—and then you’re in. No progress bar, no red tape.

Figure 1-1. Left: On Macs configured to accommodate different people at different times, this is one of the first things you see upon turning on the computer. Click your name. (If the list is long, you may have to scroll to find your name—or just type the first few letters of it.) Right: At this point, you’re asked to type in your password. Type it, and then click Log In (or press Return or Enter; pressing these keys usually “clicks” any blue, pulsing button in a dialog box). If you’ve typed the wrong password, the entire dialog box vibrates, in effect shaking its little dialog-box head, suggesting that you guess again. (See Chapter 12.)

What happens next depends on whether you’re the Mac’s sole proprietor or have to share it with other people in an office, school, or household.

If it’s your own Mac, and you’ve already been through the Mac OS X setup process described in Appendix A, no big deal. You arrive at the Mac OS X desktop.

If it’s a shared Mac, you may encounter the Login dialog box, shown in Figure 1-1. Click your name in the list (or type it, if there’s no list).

If the Mac asks for your password, type it and then click Log In (or press Return). You arrive at the desktop. Chapter 12 offers much more on this business of user accounts and logging in.

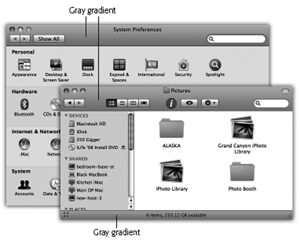

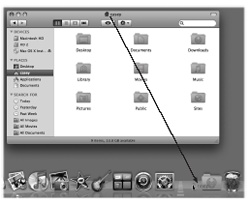

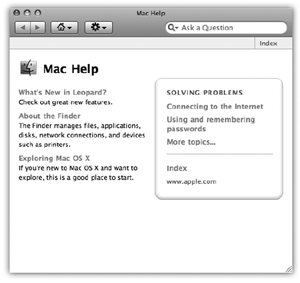

Thedesktop is the shimmering, three-dimensional Mac OS X landscape shown in Figure 1-2. On a new Mac, it’s covered by a starry galaxy photo that belongs to Leopard’s overall outer-space graphic theme.

If you’ve ever used a computer before, most of the objects on your screen are nothing more than updated versions of familiar elements. Here’s a quick tour.

Figure 1-2. The Mac OS X landscape looks like a more futuristic version of the operating systems you know and love. This is just a starting point, however. You can dress it up with a different background picture, adjust your windows in a million ways, and, of course, fill the Dock with only the programs, disks, folders, and files you need.

Note

If your desktop looks even barer than this—no menus, no icons, almost nothing on the Dock—then somebody in charge of your Mac has turned on Simple Finder mode for you. Details on System.

Here they are, just where they’ve always been: the icons of your hard drive and any other disks attached to your Mac. Double-click to open one, as always.

You may notice that icons in Mac OS X are larger than they were in previous soperating systems. You can make them almost any size you like, but Apple made them bigger for two reasons. First, in this era of monitors with ever larger resolution, the icons on our screens have been getting ever smaller and harder to see.

Second, Apple thinks its Mac OS X icons look really cool.

Note

If you find it disturbing that your desktop is littered by disk icons — and you prefer the setup in Windows, where disks remain safely caged in the My Computer window — Leopard can accommodate you. Choose Finder → Preferences, click General, and turn off the checkboxes of the disks whose icons you don’t want on the desktop: Hard disks, External disks, and so on.

From now on, you’ll have to look in the Sidebar (Windows and How to Work Them) or the Computer window (Go → Computer) to find those disk icons.

This row of translucent, almost photographic icons is a launcher for the programs, files, folders, and disks you use often—and an indicator to let you know which programs are already open. In Leopard, they now rest on what appears to be a polished, highly reflective shelf.

In principle, the Dock is very simple:

Programs go on the left side. Everything else goes on the right, including documents, folders, and disks. (Figure 1-2 shows the dividing line.)

You can add a new icon to the Dock by dragging it there. Rearrange Dock icons by dragging them like tiles on a puzzle. Remove a Dock icon by dragging it away from the Dock, and enjoy the animated puff of smoke that appears when you release the mouse button. (You can’t remove the icon of a program that’s currently open, however.)

Click something once to open it. When you click a program’s icon, a tiny, shiny reflective dot appears under its icon to let you know that it’s open. (The tiny shiny dot replaces the little black triangle of Mac OS X versions gone by.)

When you click a folder’s icon, you get a stack—an arcing row of icons, or a grid of them, that indicates what’s inside. See Stacks for more on stacks.

Each Dock icon sprouts a pop-up menu. To see the menu, hold the mouse button down on a Dock icon, or Control-click it, or right-click it. A shortcut menu of useful commands pops right out.

Because the Dock is such a critical component of Mac OS X, Apple has decked it out with enough customization controls to keep you busy experimenting for months. You can change its size, move it to the sides of your screen, hide it entirely, and so on. Chapter 4 contains complete instructions for using and understanding the Dock.

The ![]() menu houses important Mac-wide commands like Sleep, Restart, and Shut Down. They’re always available, no matter which program you’re using. (In Leopard, the

menu houses important Mac-wide commands like Sleep, Restart, and Shut Down. They’re always available, no matter which program you’re using. (In Leopard, the ![]() menu looks like a dark black hole. Evidently, black is the new blue.)

menu looks like a dark black hole. Evidently, black is the new blue.)

Every popular operating system saves space by concealing its most important commands in menus that drop down. Mac OS X’s menus are especially refined:

They’re translucent.You can actually see through an open menu to whatever window is beneath. Translucent menus don’t particularly help you; in fact, inLeopard, they’re so see-through, they can be hard to read, especially when the document window behind them contains text. Consider them showoff-ware.

They stay down. Mac OS X is multithreaded, which means that it’s perfectly capable of carrying on with its background activities while you study its open, translucent menus. Therefore, Mac OS X menus stay open until you click the mouse, trigger a command from the keyboard, or buy a new computer, whichever comes first.

Tip

Actually, menus are even smarter than that. If give the menu name a quick click, the menu opens and stays open. If you click and hold the mouse button down for a moment, the menu opens, but closes again when you release the mouse button. Apple figures that, in that case, you’re just exploring, reading, or hunting for a certain command.

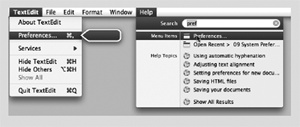

They’re logically rearranged. The first menu in every program, which appears in bold lettering, tells you at a glance what program you’re in. The commands in this Application menu include About (which indicates what version of the program you’re using), Preferences, Quit, and commands like Hide Others and Show All (which help control window clutter, as described on Hiding All Other Programs).

In short, all of the Application menu’s commands actually pertain to the application you’re using.

The File and Edit menus come next. As in the past, the File menu contains commands for opening, saving, and closing files. (See the logic?) The Edit menu contains the Cut, Copy, and Paste commands.

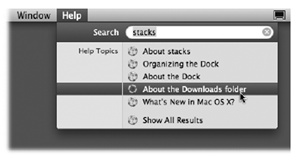

The last menu is almost always Help. It opens a miniature Web browser that lets you search the online Mac Help files for explanatory text (Shut Down).

You can operate them from the keyboard. Once you’ve clicked open a menu, you can highlight any command in it just by typing the first letter (g for Get Info, for example). (It’s especially great for “Your country” pop-up menus on Web sites, where “United States” is about 200 countries down in the list. Now you can type united s to jump right to it.)

You can also press Tab to open the next menu, Shift-Tab to open the previous one, and Enter to “click” the highlighted command.

All that’s left is figuring out a way to open the menu from the keyboard to start the process (details on Reassigning all documents of one type).

Otherwise, the menu bar looks and works much as it has in operating systems past.

In designing Mac OS X, one of Apple’s key goals was to address the window-proliferation problem. As you create more files, stash them in more folders, and launch more programs, it’s easy to wind up paralyzed before a screen awash with cluttered, overlapping rectangles.

That’s the problem addressed by Exposé, a useful feature that’s probably worth at least $34 of Mac OS X’s $130 price, and Spaces, which is easily worth another $17.35. They’re described in detail on pages Exposé: Death to Window Clutter and Multiple-button mouse clicks.

There are some handy clutter and navigation controls on the windows themselves, too. For example:

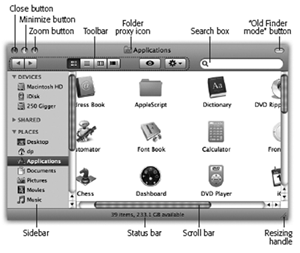

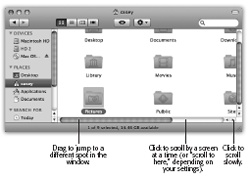

The Sidebar is the pane at the left side of every Finder window, unless you’ve hidden it (and, by the way, also at the left side of every Open dialog box and full-sized Save dialog box).

The Sidebar has been overhauled in Leopard. Now this list has as many as four different sections, each preceded by a collapsible heading:

Devices. This section lists every storage device connected to, or installed inside, your Mac: hard drives, CDs, DVDs, iPods, memory cards, USB flash drives, and so on. The removable ones (CDs, DVDs, iPods, and so on) bear a little gray

logo, which you can click to eject that disk.

logo, which you can click to eject that disk.Shared. It took 20 years for an operating system to list all the other computers on the home or small-office network, right there in every window, without any digging, connecting, button-clicking, or window-opening. But here it is: a complete list of the other computers on your network whose owners have turned on File Sharing, ready for access. See Chapter 13 for complete details.

Places. This primary section of the sidebar lists places (in this case, folders) where you might look for files and folders. Into this list, you can stick the icons of anything at all—files, programs, folders, disks, or whatever—for easy access.

Each icon is a shortcut. For example, click the Applications icon to view the contents of your Applications folder in the main part of the window (Figure 1-3). And if you click the icon of a file or program, it opens.

Searches. The "folders” in this new Sidebar section are actually canned searches that execute instantly when you click one. If you click Today, for example, the main window fills with all files and folders on your computer that you’ve changed today. Yesterday and Past Week work the same way.

Figure 1-3. The Sidebar makes navigation very quick, because you can jump back and forth between distant corners of your Mac with a single click. In column view, the Sidebar is especially handy because it eliminates all of the columns to the left of the one you want, all the way back to your hard-drive level. You’ve just folded up your desktop! Good things to put here: favorite programs; disks on the network to which you often connect; a document you’re working on every day; and so on. Folder and disk icons here work just like normal ones. You can drag a document onto a folder icon to file it there, drag a downloaded .sit file onto the StuffIt Expander icon there, and so on. In fact, the disks and folders here are even spring-loaded (Spring-Loaded Folders: Dragging Icons into Closed Folders).

The All Images, All Movies, and All Documents searches round up everything in those file-type categories, no matter what folders they’re actually sitting in.

These insta-searches are very useful all by themselves, but what’s even better is how easy it is to make your own search folders to put here. Smart Folders has the details.

The beauty of this parking lot for containers is that it’s so easy to set up with your favorite places. For example:

Remove an icon by dragging it out of the Sidebar entirely. It vanishes with a puff of smoke (and even a little whoof sound effect). You haven’t actually removed anything from your Mac; you’ve just unhitched its alias from the Sidebar.

Tip

You can’t drag Shared items out of the list. Also, if you drag a Devices item out of the list, you’ll have to choose Finder→Preferences to put it back in; see the box on Title Bar.

Rearrange the icons by dragging them up or down in the list. (You’re not allowed to rearrange the computers listed in the Shared section, though.)

Install a new iconby dragging it off your desktop (or out of a window) into any spot in the Places list of the Sidebar. Unlike previous versions of Mac OS X, you can’t drag icons into any old section of the sidebar—just the Places place.

Adjust the width of the Sidebar by dragging its right edge—either the skinny divider line or the extreme right edge of the vertical scroll bar, if there is one. You “feel” a snap at the point when the line covers up about half of each icon’s name. Any covered-up names sprout ellipses (…) to let you know (as in “Secret Salaries Spreadsh…”).

Note

The Leopard Sidebar is a lot less flexible than the old one. For example, you can no longer drag the divider bar so far to the left that it hides the icons’ names. It stops just to the left of the end of the longest name.

Nor can you hide the Sidebar completely by double-clicking the dividing line, by pressing Control-Option-⌘-T, or by dragging the line all the way to the left. None of those methods work anymore; the only way to hide the Sidebar is to use the Old Finder Mode button.

Hide the Sidebar by clicking the Old Finder Mode button, a white, capsule-like button in the upper-right corner of the window, or using its menu equivalent (View→Hide Toolbar). (See Old Finder Mode: The Toolbar Disclosure Button for more on the Old Finder Mode button.)

Then again, why would you ever want to hide the Sidebar? It’s one of the handiest navigation aids since the invention of the steering wheel. For example:

It takes a lot of pressure off the Dock. Instead of filling up your Dock with folder icons (all of which are frustratingly alike and unlabeled anyway), use the Sidebar to store them. You leave the Dock that much more room for programs and documents.

It’s better than the Dock.In some ways, the Sidebar is a lot like the Dock, in that you can stash favorite icons there of any sort. But the Sidebar reveals the names of these icons, and the Dock doesn’t.

It makes disk-ejecting easy.Just click the

button next to any removable disk to make it pop out. After 20 years, the Mac finally beats the “It’s illogical to eject a disk by dragging it to the Trash!” problem. (For other ways to eject disks, see Flash drives.)

button next to any removable disk to make it pop out. After 20 years, the Mac finally beats the “It’s illogical to eject a disk by dragging it to the Trash!” problem. (For other ways to eject disks, see Flash drives.)It makes disc-burning easy.When you’ve inserted a blank CD or DVD and loaded it up with stuff you want to copy, click the radioactive-looking Burn button next to its name to begin burning that disc. (Details on burning discs in Chapter 11.)

You can drag onto its folders and disks.That is, you can drag icons onto Sidebar icons, exactly as though they were the real disks, folders, and programs that they represent.

It simplifies connecting to networked disks. Park your other computers’ hard drive icons here, as described in Chapter 12, and you shave several steps off the usual connecting-via-network ritual.

The title bar (Figure 1-4) has several functions. First, when several windows are open, the darkened title bar, window name, mini-icon, and colored left-corner buttons tell you which window is active (in front); in background windows, these elements appear dimmed and colorless. Second, the title bar acts as a handle that lets you move the window around on the screen.

appear dimmed and colorless. Second, the title bar acts as a handle that lets you move the window around on the screen.

Of course, you can also move Mac OS X windows by dragging any “shiny gray” edge; see Figure 1-4.

Tip

Here’s a nifty keyboard shortcut: You can cycle through the different open windows in one program without using the mouse. Just press ⌘-~ (that is, the tilde key, to the left of the number 1 key). With each press, you bring a different window forward within the current program. It works both in the Finder and in your everyday programs, and it beats the pants off using the mouse to choose a name from the Window menu.

Figure 1-4. Mac OS X is no longer made of simulated brushed aluminum. Now it’s accented with strips of gradient gray (that is, light-to-dark shading). Any of these gradient gray strips are fair game as handles to drag the window.

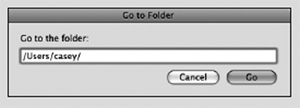

After you’ve opened one folder that’s inside another, the title bar’s secret folder hierarchy menu is an efficient way to backtrack—to return to the enclosing window. Get in the habit of right-clicking (or Control-clicking, or ⌘-clicking) the name of the window to access the menu shown in Figure 1-5. (You can release the Control or ⌘key immediately after clicking.)

By choosing the name of a folder from this menu, you open the corresponding window. When browsing the contents of the Users folder, for example, you can return to the main hard drive window by Control-clicking the folder name Users and then choosing Macintosh HD from the menu. (The option to Control- or right-click for this function is new in Leopard.)

Tip

Keyboard lovers, take note. Instead of using this title bar menu, you can also jump to the enclosing window by pressing ⌘-up arrow, which is the shortcut for the Go→Enclosing Folder command.

Figure 1-5. Control-click (or right-click, or ⌘-click) a Finder window’s title bar to summon the hidden folder hierarchy menu. This trick also works in most other Mac OS X programs. For example, you can ⌘-click a document window’s title to find out where the document is actually saved on your hard drive.

Pressing ⌘-down arrow takes you back into the folder you started in, assuming that it’s still highlighted. (This makes more sense when you try it than when you read it.)

Once you’ve mastered dragging, you’re ready for these three terrific title bar tips:

Pressing the ⌘ key lets you drag the title bar of an inactive window—one that’s partly covered by a window in front—without bringing it to the front. (Drag any empty part of the title bar—not the title itself.)

By the way, you can close, minimize, or zoom a background window without the help of the ⌘key. Just click one of those three corresponding title-bar buttons normally. Mac OS X does its thing without taking you out of your current window or program.

Tip

In previous Mac OS X versions, you could press the ⌘ key to operate any control—resize boxes, pop-up menus, and even scroll bars—in a background window without bringing it to the front. But no longer; in Leopard, you can’t operate those window features when they’re in the background, with or without the ⌘ key.

By double-clicking the title bar,you minimize the window, making it collapse into the Dock exactly as though you had clicked the Minimize button (assuming you haven’t turned off this feature in System Preferences, of course).

The Option key means “Apply this action to all windows in the current program.” For example, Option-double-clicking any title bar minimizes all desktop windows, sending them flying to the Dock.

As the tip of your cursor crosses the three buttons at the upper-left corner of a window, tiny symbols appear inside them: x, -, and +. Ignore the gossip that these symbols were added to help color-blind people who can’t distinguish the colors red, yellow, and green. Color-blind people are perfectly capable of distinguishing the buttons by their positions, just as they do with traffic lights.

Instead,these cues appear to distinguish the buttons when all three are identical shades of gray, as they are when you use Graphite mode(page142).They also signal you when it’s time to click. For example, as described in the previous section, you can use these three buttons even when the window is not frontmost.You know the buttons are ripe for the clicking when you see the little symbols appear under your cursor.

The most important window gadget is the Close button, the red, droplet-like button in the upper-left corner (Figure 1-6). Clicking it closes the window, which collapses back into the icon from which it came.

Tip

If, while working on a document, you see a tiny dot in the center of the Close button, Mac OS X is trying to tell you that you haven’t yet saved your work. The dot goes away when you save the document.

Figure 1-6. When Steve Jobs unveiled Mac OS X at a Macworld Expo in 1999, he said that his goal was to oversee the creation of an interface so attractive, “you just want to lick it.” Desktop windows, with their juicy, fruit-flavored controls, are a good starting point.

The universal keyboard equivalent of the Close button is ⌘-W (for window)—a keystroke well worth memorizing. If you get into the habit of dismissing windows with that deft flex of your left hand, you’ll find it far easier to close several windows in a row, because you don’t have to aim for successive Close buttons.

In many programs, something special happens if you’re pressing the Option key when using the Close button or its ⌘-W equivalent: You close all open windows. This trick is especially useful in the Finder, where a quest for a particular document may have left your screen plastered with open windows for which you have no further use. Option-clicking the Close button of any one window (or pressing Option-→-W) closes all of them.

On the other hand, the Option-key trick doesn’t close all windows in every program—only those in the current program. Option-closing a Pages document closes all Pages windows, but your Finder windows remain open.

Moreover, Option-closing works only in enlightened applications. (In this department, Microsoft is not yet enlightened.)

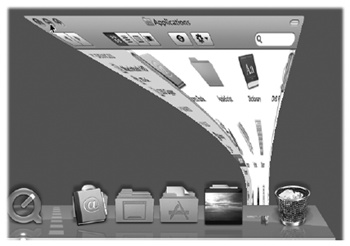

Click this yellow drop of gel to minimize any Mac window, sending it shrinking, with a genie-like animated effect, into the right end of the Dock, where it then appears as an icon. The window isn’t gone, and it hasn’t even closed. It’s just out of your way for the moment, as though you’ve set it down on a shelf. To bring it back, click the newly created Dock icon; see Figure 1-7, as well as Chapter 4 for more on the Dock.

Minimizing a window in this way is a great window-management tool. In the Finder, minimizing a window lets you see whatever icons were hiding behind it. In a word processor, this technique lets you type a memo that requires frequent consultation of a spreadsheet behind it.

Figure 1-7. Clicking the Minimize button sends a window scurrying down to the Dock, collapsing in on itself as though being forced through a tiny, invisible funnel. A tiny icon appears on the lower-right corner of its minimized image to identify the program it’s running in.

Tip

If you enjoy the ability to roll up your windows in this way, remember that you actually have a bigger target than the tiny Minimize button. The entire title bar becomes a giant Minimize button when you double-click anywhere on it. (That’s an option in the Appearance panel of System Preferences, described in System Preferences.)

Better yet, you can also minimize the frontmost window of almost any program (including the Finder) from the keyboard by pressing ⌘-M. That’s a keystroke worth memorizing on Day One.

The Minimize button harbors a very entertaining hidden feature. If you Option-click it, all windows in the current program shrink away simultaneously—great when you’ve got several Web browser windows open, for example, or an abundance of word processor documents.

You might expect that Option-clicking one minimized window on the Dock would un-minimize all of a program’s windows—and indeed, that’s true for Cocoa programs (page185). But if it’s a Carbon program, like the Finder, you have to click the windows one at a time on the Dock to bring them back.

Tip

Mac OS X can even change menu commands as you press modifier keys. For example, open a couple of Finder windows and then click the Window menu. Focus your eyes on the Minimize Window command. Now press Option and watch both the wording and the listed keyboard equivalent change instantly to Minimize All (Option-⌘-M).

The Option key works wonders on the File menu, too.

A click on this green geltab (see Figure 1-6) makes a desktop window just large enough to reveal all of the icons inside it (or, in application programs, large enough to reveal all the text, or graphics, or music). If your monitor isn’t big enough to show all the icons in a window, the zoom box resizes the window to show as many as possible.

In either case, a second click on the Zoom button restores the window to its previous size. (The Window→Zoom command does the same thing.)

Each Finder-window title bar features a small icon next to the window’s name (Figure 1-8), representing the open window’s actual folder or disk icon. It’s a stand-in—a proxy—for the folder itself.

By dragging this tiny icon, you can move or copy the folder into a different folder or disk, into the Sidebar, into the Trash, or into the Dock without having to first close the window.

Tip

You have to hold down the mouse button on the folder proxy icon until the icon darkens before dragging. (It darkens in a fraction of a second.)

Figure 1-8. When you find yourself confronting a Finder window that contains useful stuff, consider dragging its proxy icon to the Dock. You wind up installing its folder or disk icon there for future use. That’s not the same as minimizing the window, which puts the window icon into the Dock, and only temporarily at that. (Note: Most Mac OS X document windows also offer a proxyicon feature, but produce only an alias when you drag the proxy to a different folder or disk.)

When you drag this proxy icon to a different place on the same disk, the usual folder dragging rules apply: Hold down the Option key if you want to copy the original disk

or folder; ignore the Option key to move the original folder. (You’ll find details on moving and copying icons in the next chapter.)

Chapter 4 describes this fascinating desktop-window element in great detail.

In Mac OS X, double-clicking a folder in a window doesn’t leave you with two open windows. Instead, double-clicking a folder makes the original window disappear (Figure 1-9).

Tip

If you Option-double-click a folder, you don’t simply replace the contents of a fixed window that remains onscreen; you actually switch windows, as evidenced by their changing sizes and shapes.

Figure 1-9. To help you avoid window clutter, Apple has designed Mac OS X windows so that double-clicking a folder in a window (top) doesn’t actually open another window (bottom). Every time you double-click a folder in an open window (except in column view), its contents replace whatever was previously in the window. If you double-click three folders in succession, you still wind up with just one open window.

So what if you’ve now opened inner folder B, and you want to backtrack to outer folder A? In that case, just click the tiny ![]() button—the Backbutton —in the upper-left corner of the window (shown in Figure 1-9), or use one of these alternatives:

button—the Backbutton —in the upper-left corner of the window (shown in Figure 1-9), or use one of these alternatives:

Choose Go→Back.

Press ⌘-[ (left bracket).

Press ⌘-up arrow.

Choose Go→Enclosing Folder.

None of that helps you, however, if you want to move a file from one folder into another, or compare the contents of two windows. In that case, you probably want to see both windows open at the same time.

You can open a second window using any of these techniques:

Choose File→New Finder Window (⌘-N).

Tip

What folder contents fill the “new” window that appears when you use this command? Usually, it’s your Home folder, the folder that contains your entire universe of files, folders, and settings.

But you can choose any window you want. To make the change, choose Finder→Preferences. Click the General icon. Change the “New Finder windows open” pop-up menu to whatever folder you’d like to use as the starting point for your computing life. Your Home folder is a good choice, but you’re also free to choose your Documents folder, your iDisk, or any folder at all. Now every new Finder window shows you that specified folder, which is a much more useful arrangement.

⌘-double-click a disk or folder icon.

Double-click a folder or disk icon on your desktop.

Choose Finder→Preferences and turn on “Always open folders in a new window.” Now when double-clicked, all folders open in to their own new windows. (This is the option for veteran Mac fans who don’t care for the new behavior.)

The upper-right corner of every Finder window contains a little button that looks like a half-inch squirt of Crest toothpaste. When you click it, you enter Old Finder Mode.

Tip

You can also turn Old Finder Mode on or off by pressing Option-⌘-T, the equivalent for the View→Hide Toolbar command.

"Old Finder Mode,” of course, isn’t the technical Apple term, but it should be. It was designed for people who come to Mac OS X from an earlier version of the Mac OS, like Mac OS 9, and lose half their hair when they discover how different things are in Mac OS X.

In this mode, three of the biggest behavioral differences between Mac OS X and its predecessor disappear:

The Sidebar and the toolbar blink out of sight.

Double-clicking a folder now works like it did back in 2000. Every time you doubleclick a folder, you open a new corresponding window.

You can add a Mac OS 9–style information strip at the top of the window, which tells you how many icons are in it (“14 items,” for example) and the amount of free space remaining on the disk. Just choose View→Show Status Bar—a command that’s dimmed at all timesexcept when you’re in Old Finder Mode.

(When you’re not in Old Finder mode, this information strip appears at the bottom of every Finder window, as shown in Figure 1-6. And the Show Status Bar command is always dimmed.)

When you’ve had enough of Old Finder Mode, you can return to regular Mac OS X mode either by clicking the Toolbar Disclosure button again, by pressing Option-⌘-T again, or by choosing View→Show Toolbar.

Scroll bars appear automatically in any window that isn’t big enough to show all of its contents. Without scroll bars in word processors, for example, you’d never be able to write a letter that’s longer than your screen is tall. You can manipulate a scroll bar in three ways, as shown in Figure 1-10.

Mac OSX offers an intriguing scroll bar option called"Jump to here."Ordinarily, when you click in the scroll bar track above or below the gelatinous handle, the window scrolls by one screenful. But your other option is to turn on “Scroll to here” mode in the Appearance panel of System Preferences (Accounts). Now when you click in the scroll bar track, the Mac considers the entire scroll bar a proportional map of the document, and jumps precisely to the spot you clicked. That is, if you click at the very bottom of the scroll bar track, you see the very last page.

Figure 1-10. Three ways to control a scroll. The scroll bar arrows (lower right) appear nestled together when you first install Mac OS X, as shown here. If you, an old-time Windows or Mac OS 9 fan, prefer these arrows to appear on opposite ends of the scroll bar, visit the Appearance panel of System Preferences, described on Accounts.

Figure 1-11. Position your mouse inside a Finder list-view window. You can scroll up and down by pressing ⌘ and Option as you drag. As you drag, the cursor changes shape, becoming a white-gloved butler’s hand. Where can you get that kind of service these days? (This trick now works in icon views, too, which it didn’t in Mac OS X 10.4; it actually lets you scroll diagonally, which is even more useful.)

Tip

No matter which scrolling option you choose in the Appearance panel, you can always override your decision on a case-by-case basis by Option-clicking in the scroll bar track. In other words, if you’ve selected the “Jump to here” option, you can produce a “Jump to the next page” scroll by Option-clicking in the scroll bar track.

It’s worth noting, however, that the true speed expert eschews scroll bars altogether. Your Page Up and Page Down keys let you scroll up and down, one screen at a time, without having to take your hands off the keyboard to grab the mouse. The Home and End keys, meanwhile, are generally useful for jumping directly to the top or bottom of your document (or Finder window). And if you’ve bought a mouse that has a scroll wheel on the top, you can use it to scroll windows, too, without pressing any keys at all.

And then there’s the utterly obscure, but charming, diagonal-scrolling method, newly enhanced in Leopard, which is shown in Figure 1-11.

The lower-right corner of every standard Mac OS X window is ribbed, a design that’s meant to imply that you can grip it by dragging. Doing so lets you resize and reshape the window (Figure 1-6).

This little item, new in Leopard, appears when you choose View→Show Path Bar. It’s a tiny map at the bottom of the window that shows where you are in the folder hierarchy. If it says Casey ![]() Pictures

Pictures ![]() Picnic, well, then, by golly, you’re looking at the contents of the Picnic folder, which is inside Pictures, inside your Home folder.

Picnic, well, then, by golly, you’re looking at the contents of the Picnic folder, which is inside Pictures, inside your Home folder.

The information strip at the bottom of a window tells you how many icons are in the window (“14 items,” for example) and the amount of free space remaining on the disk. (If you miss seeing the status bar at the top of every window—what are you, some kind of radical?—see Old Finder Mode: The Toolbar Disclosure Button.)

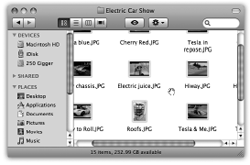

You can view the files and folders in a desktop window in any of four ways: as icons; as a single, tidy list; in a series of neat columns; or—new in Leopard—as giant document icons that you flip through like they’re CDs in a record-store bin (called Cover Flow view). Figure 1-12 shows the four different views.

Every window remembers its view settings independently. You might prefer to look over your Applications folder in list view (because it’s crammed with files and folders), but you may prefer to view the Pictures folder in icon or Cover Flow view, where the larger icons serve as previews of the photos.

Figure 1-12. From the top: The same window in icon view, list view, column, and Cover Flow views. Very full folders are best navigated in list or column views, but you may prefer to view emptier folders in icon or Cover Flow views, because larger icons are easier to preview and click. Remember that in any view (icon, list, column, or Cover Flow), you can highlight an icon by typing the first few letters of its name. In icon, list, or Cover Flow view, you can also press Tab to highlight the next icon (in alphabetical order), or Shift-Tab to highlight the previous one.

To switch a window from one view to another, just click one of the four corresponding icons in the window’s toolbar, as shown in Figure 1-12.

You can also switch views by choosing View→as Icons (or View→as Columns, or View→as List, or View→as Cover Flow), which can be handy if you’ve hidden the toolbar. Or, for less mousing and more hardbodied efficiency, press ⌘-1, ⌘-2, ⌘-3, or ⌘-4 for icon, list, column, or Cover Flow view, respectively.

The following pages cover each of these views in greater detail.

Note

One common thread in the following discussions is the availability of the View Options palette, which lets you set up the sorting, text size, icon size, and other features of each view, either one window at a time or for all windows.

Apple gives you a million different ways to open View Options. You can choose View→Show View Options, or press ⌘-J, or choose Show View Options from the ![]() menu at the top of every window.

menu at the top of every window.

In an icon view, every file, folder, and disk is represented by a small picture—an icon. This humble image, a visual representation of electronic bits and bytes, is the cornerstone of the entire Macintosh religion. (Maybe that’s why it’s called an icon.)

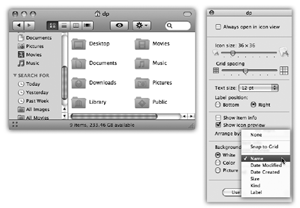

Mac OS X offers a number of useful icon-view options, all of which are worth exploring. Start by opening any icon view window, and then choose View→Show View Options (⌘-J).

In Mac OS X Leopard, it’s easy—almost scarily easy—to set up your preferred look for all folder windows on your entire system. With one click on the “Use as Defaults” button (described below), you can change the window view of 20,000 folders at once—to icon view, list view, or whatever you like.

The “Always open in icon view” option lets you override that master setting, just for this window.

For example, you might generally prefer a neat list view with large text. But for your Pictures folder, it probably makes more sense to set up icon view, so you can see a thumbnail of each photo without having to open it.

That’s the idea here. Open Pictures, change it to icon view, and then turn on “Always open in icon view.” Now every folder on your Mac is in list view except Pictures.

Note

The wording of this item in the View Options dialog box changes according to the view you’re in at the moment. In a list-view window, for example, it says “Always open in list view.” In a Cover Flow–view window, it says “Always open in Cover Flow.” And so on. But the function is the same: to override the default (master) setting.

Mac OS X draws the little pictures that represent your icons using sophisticated graphics software. As a result, you (or the Mac) can scale them to almost any size without losing any quality or clarity.

In the View Options window (Figure 1-13), drag the Icon Size slider back and forth until you find a size you like. (For added fun, make little cartoon sounds with your mouth.)

Listen up, you young whippersnappers! When I was your age, back when computers used Mac OS 9, you could control how closely spaced icons were in a window. Why, if I wanted to see a lot of them without making the window bigger, I could pack’em in like sardines!

That feature disappeared—for seven years. But it’s finally returned to Mac OS X. Figure 1-14 shows all.

Your choices range only from 10 to 16 points, and you still can’t choose a different font for your icons’ names. But using this slider, you can adjust the type size. And for people with especially big or especially small screens—or people with aging retinas—this feature is much better than nothing.

Figure 1-14. Drag the “Grid spacing” slider to specify how tightly packed you want your icons to be. At the minimum setting (top), they’re so crammed that it’s almost ridiculous; you can’t even see their names. But sometimes, you don’t really need to. At more spacious settings (bottom), you get a lot more “white space.”

In fact,you can actually specify a different type size for every window on your machine. (Why would you want to adjust the point size independently in different windows? Well, because you might want smaller type to fit more into a crammed list view without scrolling, while you can afford larger type in less densely populated windows.)

Click either Bottom or Right to indicate where you want an icon’s name to appear, relative to its icon.

In its own quiet way, this tiny, unheralded feature represents one of the most radical changes to the Finder since the invention of the Mac. As shown in Figure 1-15, it lets you create, in effect, a multiple-column list view in a single window.

While you’ve got the View Options palette open, try turning on “Show item info.” Suddenly you get a new line of information (in tiny blue type) for certain icons, saving you the effort of opening up the folder or file to find out what’s in it. For example:

Folders.The info line lets you know how many icons are inside each without having to open it up. Now you can spot empties at a glance.

Graphics files.Certain other kinds of files may show a helpful info line, too. For example, graphics files display their dimensions in pixels.

Sounds and QuickTime movies.The light-blue bonus line tells you how long the sound or movie takes to play. For example, an MP3 file might say “03’ 08,” which means three minutes, eight seconds.

.zip files.On compressed archives like .zip files (Installing Mac OS X Programs), you get to see the archive’s total size on disk (like “48.9 MB”).

You can see some of these effects illustrated in Figure 1-15.

Figure 1-15. The View Options dialog box for an icon view window offers the chance to create colored backgrounds for certain windows or even to use photos as window wallpaper (bottom). Using a photo may have a soothing, annoying, or comic effect—like making the icon names completely unreadable. (Note, by the way, how the icon’s names have been set to appear beside the icons, rather than underneath. You now have all the handy, freely draggable convenience of an icon view, along with the more compact spacing of a list view.)

This option pertains primarily to graphics, which Mac OS X often displays only with a generic icon (stamped with the file type, like JPEG, TIFF, or PDF). But if you turn on “Show icon preview,” Mac OS X turns each icon into a miniature display of the image itself, as shown in Figure 1-15. It’s ideal for working with folders full of digital photos.

Tip

A small but delicious point: You can tell just by looking at a PDF file’s icon whether it’s longer than one page. The icon for a one-page PDF has a curled upper-right corner. But on a multi-page PDF, only the first page’s corner curls down. And in the gap it reveals, you can see a tiny bit of the actual What’s New in Leopard showing!

Here’s another Mac OS X luxury that other operating systems can only dream about: You can fill the background of any icon view window on your Mac with a certain color—or even a photo.

Color-coordinating or “wallpapering” certain windows is more than just a gimmick. In fact, it can serve as a timesaving psychological cue. Once you’ve gotten used to the fact that your main Documents folder has a sky-blue background, you can pick it out like a sharpshooter from a screen filled with open windows. Color-coded Finder windows are also especially easy to distinguish at a glance when you’ve minimized them to the Dock.

Once a window is open,choose View→View Options (⌘-J). The bottom of the resulting dialog box offers three choices, whose results are shown in Figure 1-15.

White. This is the standard option (not shown).

Color.When you click this button, you see a small rectangular button beside the word Color. Click it to open the Color Picker (Dashboard), which you can use to choose a new background color for the window. (Unless it’s April Fool’s Day, pick a light color. If you choose a dark one—like black—you won’t be able to make out the lettering of the icons’ names.)

Picture.If you choose this option, a Select button appears. Click it to open the Select a Picture dialog box, already open to your Library → Desktop Pictures folder. Now choose a graphics file—one of Apple’s in the Desktop Pictures folder, or one of your own. When you click Select, you see that Mac OS X has superimposed the window’s icons on the photo. As you can see in Figure 1-15, low-contrast or light-background photos work best for legibility.

Incidentally,the Mac has no idea what sizes and shapes your window may assume in its lifetime. Therefore, Mac OS X makes no attempt to scale down a selected photo to fit neatly into the window. If you have a high-res digital camera, therefore, you see only the upper-left corner of a photo in the window. Use a graphics program to scale the picture down to something smaller than your screen resolution for better results.

This harmless-looking button can actually wreak havoc—or restore order to your kingdom—with a single click. It applies the changes you’ve just made in the View Options dialog box to all windows on your Mac (instead of only the frontmost window).

If you set up the frontmost window with a colored background, big icons, small text, and a tight grid, and then you click Use as Defaults, you’ll see that look in every disk or folder window you open.

You’ve been warned.

Fortunately, there are two auxiliary controls that can give you a break from all the sameness.

First, you can set up individual windows to be weirdo exceptions to the rule; see “Always open in icon view,” above.

Second, you can remove any departures from the default window view—after a round of disappointing experimentation on a particular window, for example—using a secret button. To do so, choose View→Show View Options to open the View Options dialog box. Now hold down the Option key. The Use as Defaults button magically changes to say “Restore to Defaults,” which means “Abandon all the changes I’ve foolishly made to the look of this window.”

In general, you can drag icons anywhere within a window. For example, some people like to keep current project icons at the top of the window and move older stuff to the bottom.

If you’d like Mac OS X to impose a little discipline on you, however, it’s easy enough to request a visit from an electronic housekeeper who tidies up your icons by aligning them neatly to an invisible grid. In Leopard, you can even specify how tight or loose that grid is.

Mac OS X offers an enormous number of variations on the “snap icons to the underlying rows-and-columns grid” theme:

Aligning individual icons to the grid.Press the ⌘ key while dragging an icon or several highlighted icons. (Don’t press the key until after you begin to drag.) When you release the mouse, the icons you’ve moved all jump into neatly aligned positions.

Aligning all icons to the grid.Choose View→Clean Up (if nothing is selected) or View→Clean Up Selection (if some icons are highlighted). Now all icons in the window, or those you’ve selected, jump to the closest positions on the invisible underlying grid.

These same commands appear in the shortcut menu when you Control-click or right-click anywhere inside an icon-view window, which is handier if you have a huge monitor.

Tip

If you press Option, you swap the wording of the command. Clean Up changes to read Clean Up Selection, and vice versa.

Note, by the way, that the grid alignment is only temporary. As soon as you drag icons around, or add more icons to the window, the newly moved icons wind up just as sloppily positioned as before you tidied up.

If you want the Mac to lock all icons to the closest spot on the grid whenever you move them,choose View→Show View Options (⌘-J);from the “Arrange by"pop-up menu, choose Snap to Grid.

Even then, though, you’ll soon discover that none of these grid-snapping techniques move icons into the most compact possible arrangement. If one or two icons have wandered off from the herd to a far corner of the window, they’re merely nudged to the grid points closest to their current locations. They aren’t moved all the way back to the group of icons elsewhere in the window.

To solve that problem, use one of the sorting options described next.

If you’d rather have icons sorted and bunched together on the underlying grid — no strays allowed — make a selection from the View menu:

Sorting all icons for the moment.If you choose View → Arrange By → Name, all icons in the window snap to the invisible grid and sort themselves alphabetically. Use this method to place the icons as close as possible to each other within the window, rounding up any strays.

The other subcommands in the View → Arrange By menu work similarly(Size,Date Modified, Label, and so on), but sort the icons according to different criteria.

As with the Clean Up command, View → Arrange By serves only to reorganize the icons in the window at this moment. If you move or add icons to the window, they won’t be sorted properly. If you’d rather have all icons remain sorted and clustered, try this:

Sorting all icons permanently.You can also tell your Mac to maintain the sorting and alignment of all icons in the window, present and future. Now if you add more icons to the window, they jump into correct alphabetical position; if you remove icons, the remaining ones slide over to fill in the resulting gap. This setup is perfect for neat freaks.

To make it happen, open the View menu, hold down the Option key, and choose fromthe "Keep Arranged By” submenu(choose Name,Date Modified,orwhatever sorting criterion you like). As shown at left in Figure 1-16, your icons are now locked into sorted position, as compactly as the grid permits.

(This Option-key trick, new in Leopard, is a shortcut for choosing View→Show View Options, and then, in the resulting dialog box, choosing from the “Arrange by” submenu.)

Tip

The Option key is up to its usual tricks here; as happens so often in the Finder, it means, “reverse the usual logic.”

For example, when you open the View menu, you see either “Arrange By” (which temporarily sorts the current batch of icons) or "Keep Arranged By” (which locks present and future icons into a sorted grid). The wording depends on whether or not you’ve already turned on permanent sorting.

But the point here is that pressing the Option key once the View menu is open changes the command — from “Arrange By” to “Keep Arranged By,” or vice versa.

Figure 1-16. Use either the View menu (left) or the View Options dialog box (right) to turn on permanent cleanliness mode. From now on, you’re not allowed to drag these icons freely. You’ve told the Mac to keep them on the invisible grid, sorted the way you requested, so don’t get frustrated when you try to drag an icon into a new position and then discover that it won’t budge.

Although it doesn’t occur to most Mac fans, you can also apply any of the commands described in this section—Clean Up, Arrange, Keep Arranged—to icons lying loose on your desktop. Even though they don’t seem to be in any window at all, you can specify small or large icons, automatic alphabetical arrangement, and so on. Just click the desktop before using the View menu or the View Options dialog box.

Note

There’s only one View Options dialog box. Once it’s open, you can adjust the icon sizes or arrangement options of other windows just by clicking them. Each time you click inside a window, the View Options dialog box remains in front, changing to reflect the settings of the window you just clicked.

Incidentally, you can get rid of the View Options box the same way you summoned it: by pressing ⌘-J.

In windows that contain a lot of icons, the list view is a powerful weapon in the battle against chaos. It shows you a tidy table of your files’ names, dates, sizes, and so on. In Leopard, alternating blue and white background stripes help you read across the columns in a list-view window.

You have a great deal of control over your columns, in that you get to decide how wide they should be, which of them should appear, and in what order (except that Name is always the first column). Here’s how to master these columns:

Most of the world’s list-view fans like their files listed alphabetically. It’s occasionally useful, however, to view the newest files first, largest first, or whatever.

When a desktop window displays its icons in a list view, a convenient new strip of column headings appears (Figure 1-17). These column headings aren’t just signposts; they’re buttons, too. Click Name for alphabetical order, Date Modified to view newest first, Size to view largest files at the top, and so on.

It’s especially important to note the tiny,dark gray triangle that appears in the column you’ve most recently clicked. It shows you which way the list is being sorted.

When the triangle point supward, the oldest files, smallest files, or files beginning with numbers (or the letter A) appear at the top of the list, depending on which sorting criterion you have selected.

Tip

It may help you to remember that when the smallest portion of the triangle is at the top (![]() ), the smallest files are listed first when viewed in size order.

), the smallest files are listed first when viewed in size order.

To reverse the sorting order, click the column heading a second time. Now the newest files, largest files, or files beginning with the letter Z appear at the top the list. The tiny triangle turns upside-down.

One of the Mac’s most attractive features is the tiny triangle that appears to the left of a folder’s name in a list view. In its official documents, Apple calls these buttons disclosure triangles; internally, the programmers call them flippy triangles.

Either way, these triangles are very useful: When you click one, the list view turns into an outline, which displays the contents of the folder in an indented list, as shown in Figure 1-18. Click the triangle again to collapse the folder listing. You’re saved the trouble and clutter of opening a new window just to view the folder’s contents.

Figure 1-17. You control the sorting order of a list view by clicking the column headings (top). Click a second time to reverse the sorting order (bottom). You’ll find the identical ![]() or

or ![]() triangle—indicating the identical information —in email programs, in iTunes, and anywhere else where reversing the sorting order of the list can be useful.

triangle—indicating the identical information —in email programs, in iTunes, and anywhere else where reversing the sorting order of the list can be useful.

By selectively clicking flippy triangles, you can, ineffect, peer inside two or morefolders simultaneously, all within a single list view window. You can move files around by dragging them onto the tiny folder icons.

Tip

Once you’ve expanded a folder by clicking its flippy triangle, you can even drag a file icon out of its folder so that it’s loose in the list view window. To do so, drag it directly upward onto the column headings area (where it says Name, for example). When you release the mouse, you see that the file is no longer inside the expanded folder.

Choose View→Show View Options. In the dialog box that appears, you’re offered on/off checkboxes for the different columns of information Mac OS X can show you, as illustrated in Figure 1-19.

Figure 1-18. Click a “flippy triangle” (left) to see the list of the folders and files inside that folder (right). Or press the equivalent keystrokes: ⌘-> (to open) and ⌘-< (to close).

Date Modified. This date-and-time stamp indicates when a document was last saved. Its accuracy, of course, depends on the accuracy of your Mac’s built-in clock.

Note

Many an up-to-date file has been lost because someone spotted a very old date on a folder and assumed that the files inside were equally old. That’s because the modification date shown for a folder doesn’t reflect the age of its contents. Instead, the date on a folder indicates only when items were last moved into or out of that folder. The actual files inside may be much older, or much more recent.

Figure 1-19. The checkboxes you turn on in the View Options dialog box determine which columns of information appear in a list view window. Most people live full and satisfying lives with only the three default columns—Date Modified, Kind, and Size—turned on. But the other columns can be helpful in special circumstances; the trick is knowing what information appears there.

Date Created.This date-and-time stamp shows you when a document was first saved.

Size.With a glance, you can tell from this column how much disk space each of your file sand folders is taking up in kilobytes, megabytes, or gigabytes—whichever the Mac thinks you’ll find most helpful.

Tip

For disks and folders, you see only a dash—at first. You can, however, instruct the Mac to reveal their sizes, as described on Rearranging Columns.

Kind.In this column, you can read what kind of file each icon represents. You may see, for example, Folder, JPEG Image, Application, and so on.

Version.This column displays the version numbers of your programs. For folders and documents, you just see a dash.

Comments.This rarely seen column can actually be among the most useful. Suppose that you’re a person who uses the Comments feature (highlight an icon, choose File→Get Info, type notes about that item into the Spotlight Comments box). The option to view the first line of comments about each icon can be very helpful, especially when tracking multiple versions of your documents, as shown in Figure 1-20.

Label.Labels are colors and identifying phrases that you can slap onto icons, wherever they appear, to help you categorize and group them. For details, see Color Labels.

Even with this column turned off, you can still see an icon’s color, of course. But only by turning on this column do you get to see the text phrase that you’ve associated with each label.

The View Options for a list view include several other useful settings; choose View→ Show View Options, or press ⌘-J.

Always open in list view.Turn on this option to override your system-wide preference setting for all windows. See “Always open in icon view” on Icon View for details.

Icon size.These two buttons offer you a choice of icon size for the current window: either standard or tiny. Unlike icon view, list view doesn’t give you a size slider.

Fortunately, even the tiny icons aren’t so small that they show up blank. You still get a general idea of what they’re supposed to look like.

Text size.As described on Label position,you can change the type size for your icon labels, either globally or one window at a time.

Show columns.Turn on the columns you’d like to appear in the current window’s list view, as described in the previous section.

Use relative dates.In a list view, the Date Modified and Date Created columns generally display information in a format like this: “Sunday, March 9, 2008.” (As noted below, the Mac uses shorter date formats as the column gets narrower.) But when the “Use relative dates” option is turned on, the Mac substitutes the word “Yesterday” or “Today” where appropriate, making recent files easier to spot.

Show icon preview. Exactly as in icon view, this option turns the icons of graphics files into miniatures of the photos or images within.

Use as Defaults. Click to make your changes in the View Options box apply to all windows on your Mac. (Option-click this button to restore a wayward window back to your defaults.)

You’re stuck with the Name column at the far left of a window. However, you can rearrange the other columns just by dragging their gray column headers horizontally.If the Mac thinks you intend to drop a column to, say, the left of the column it overlaps, you’ll actually see an animated movement—indicating a column reshuffling—even before you release the mouse button.

If you place your cursor carefully on the dividing line between two column headings, you’ll find that you can drag the divider line horizontally. Doing so makes the column to the left of your cursor wider or narrower.

What’s delightful about this activity is watching Mac OS X scramble to rewrite its information to fit the space you give it. For example, as you make the Date Modified (or Created) column narrower,"Sunday,March 9,2008,2:22 PM"shrinks first to “Sun, Mar 9, 2008, 2:22 PM,” then to “3/9/08, 2:22 PM,” and finally to a terse “3/9/08.”

If you make a column too narrow, Mac OS X shortens the file names, dates, or whatever by removing text from the middle. An ellipsis (…) appears to show you where the missing text would have appeared. (Apple reasoned that truncating the ends of file names, as in some other operating systems, would hide useful information like the number at the end of"Letter to Marge 1,""Letter to Marge 2,"and so on.It would also hide the three-letter extensions, such as Thesis.doc, that may appear on file names in Mac OS X.)

For example, suppose you’ve named a Word document “Ben Affleck—A Major Force for Humanization and Cure for Depression, Acne, and Migraine Headache.” (Yes, file names can really be that long.) If the Name column is too narrow, you might see only “Ben Affleck—A Major…Migraine Headache.”

Tip

You don’t have to make the column mega-wide just to read the full text of a file whose name has been shortened. Just point to the icon’s name without clicking. After a moment, a yellow, floating balloon appears—something like a tooltip in Microsoft programs—to identify the full name.

And if you don’t feel like waiting, hold down the Option key. As you whip your mouse over truncated file names, their tooltip balloons appear instantaneously. (Both of these tricks work in list, column, or Cover Flow views—and in Save and Open dialog boxes, for that matter.)

The goal of column view is simple: to let you burrow down through nested folders without leaving a trail of messy, overlapping windows in your wake.

The solution is shown in Figure 1-21. It’s a list view that’s divided into several vertical panes. The first pane (not counting the Sidebar) shows whatever disk or folder you first opened.

When you click a disk or folder in this list (once), the second pane shows a list of everything in it. Each time you click a folder in one pane, the pane to its right shows what’s inside. The other panes slide to the left, sometimes out of view. (Use the horizontal scroll bar to bring them back.) You can keep clicking until you’re actually looking at the file icons inside the most deeply nested folder.

Figure 1-21. If the rightmost folder contains pictures, sounds, Office documents, or movies, you can look at them or play them, right there in the Finder. You can drag this jumbo preview icon anywhere—into another folder or the Trash, for example.

If you discover that your hunt for a particular file has taken you down a blind alley, it’s not a big deal to backtrack, since the trail of folders you’ve followed to get here is still sitting before you on the screen. As soon as you click a different folder in one of the earlier panes, the panes to its right suddenly change, so that you can burrow down a different rabbit hole.

Furthermore, the Sidebar is always at the ready to help you jump to a new track; just click any disk or folder icon there to select a new first-column listing for column view.

The beauty of column view is, first of all, that it keeps your screen tidy. It effectively shows you several simultaneous folder levels, but contains them within a single window. With a quick ⌘-W, you can close the entire window, panes and all. Second, column view provides an excellent sense of where you are. Because your trail is visible at all times, it’s much harder to get lost—wondering what folder you’re in and how you got there—than in any other window view.

Note

In Leopard, for the first time, you can change how Column view is sorted; it doesn’t have to be alphabetical. Press ⌘-J to open the View Options dialog box, and then choose the sorting criterion you want from the “Arrange by” pop-up menu (like Size, Date Created, or Label).

Efficiency fans can operate this entire process by keyboard alone. For example:

You can jump from one column to the next by pressing the right or leftar row keys.

Each press highlights the first icon in the next or previous column.

You can use any ofthe commands in the Go menu,or their keyboard equivalents,or the icons in the Sidebar, to fill your columns with the contents of the corresponding folder—Home, Favorites, Applications, and so on.

The Back command(clicking the

button on the toolbar,pressing ⌘-[,or choosing Go→Back) works as it does in a Web browser:It retraces your steps backward.You can repeat this command until you return to the column setup that first appeared when you switched to column view. Once you’ve gone back, in fact, you can then go forward again; choose Go→Forward, or press ⌘-].

button on the toolbar,pressing ⌘-[,or choosing Go→Back) works as it does in a Web browser:It retraces your steps backward.You can repeat this command until you return to the column setup that first appeared when you switched to column view. Once you’ve gone back, in fact, you can then go forward again; choose Go→Forward, or press ⌘-].With in a highlighted column,press the up or down arrow keys to highlight successive icons in the list. Or type the first couple of letters of an icon’s name to jump directly to it.

When you finally highlight the icon you’ve been looking for, press ⌘ -O or ⌘ -down arrow to open it (or double-click it,of course).You can open anything in any column; you don’t have to wait until you’ve reached the rightmost column.

The number of columns you can see without scrolling depends on the width of the window. In no other view are the zoom and resize controls as important as they are here.

That’s not to say, however, that you’re limited to four columns (or whatever fits on your monitor). You can make the columns wider or narrower—either individually or all at once—to suit the situation, according to this scheme:

To make a single column wider or narrower, drag its right-side handle (circled in Figure 1-22).

To make all the columns wider or narrower simultaneously, hold down the Option key as you drag that right-side handle.

And here’s the tip of the week: Double-click one of the right-side handles to make the column precisely as wide as necessary to reveal all the names of its contents.

Best of all, you can Option-double-click any column’s right-side handle to make all columns just as wide as necessary.

Just as in icon and list view, you can choose View → Show View Options to open a dialog box—a Spartan one, in this case—offering additional control over your column views.

Always open in column view.Once again,this option lets you override your systemwide preference setting for all windows. See “Always open in icon view” on Icon View for details.

Text size.Whatever point size you choose here affects the type used for icons in allcolumn views.

Show icons.For maximum speed, turn off this option. Now you see only file names—not the tiny icons next to them—in all column views.

Show icon preview. In Leopard, for the first time, you can request that the tiny icons in column view display their actual contents—photos show their images, Word and PDF documents show the first page, and so on. Of course, this feature isn’t always terrifically useful, since the icons are the size of a hydrogen atom; but now and then, you can get the general gist of what’s in a file just by its overall shape and color.

Show preview column.The far-right Preview column can be handy when you’re browsing graphics, sounds, or movie files. Feel free to enlarge this final column when you want a better view of the picture or movie; you can make it really big. Almost Quick Look big.

The rest of the time, though, the Preview column can get in the way, slightly slowing down the works and pushing other, more useful columns off to the left side of the window. If you turn off this checkbox, the Preview column doesn’t appear.

The new, fourth view in Leopard is one of Apple’s favorites; it’s one of the handful of Leopard features that gets the most play in Apple’s advertising and demos.

As you can sort of see from Figure 1-23, Cover Flow is a visual display that Apple stole from its own iTunes software, where Cover Flow simulates the flipping “pages” of a jukebox, or the CDs in a record-store bin. There, you can flip through your music collection, marveling as the CD covers flip over in 3-D space while you browse.

Figure 1-23. The bottom half of a Cover Flow window is identical to list view. The top half, however, is an interactive, scrolling “CD bin” full of your own stuff. It’s especially useful for photos, PDF files, Office documents, and text documents. And when a movie comes up in this virtual data jukebox, you can point to the little ![]() button and click it to play the video, right in place.

button and click it to play the video, right in place.

The idea is the same in Mac OS X, except that now it’s not CD covers you’re flipping; it’s gigantic file and folder icons.

To fire up Cover Flow, open a window. Then click the Cover Flow button identified in Figure 1-23, or choose View→as Cover Flow, or press ⌘-4.

Now the window splits. On the bottom: a traditional list view, complete with sortable columns, exactly as described above.

On the top: the gleaming, reflective, black Cover Flow display. Your primary interest here is the scroll bar. As you drag it left or right, you see your own files and folders float by and flip in 3-D space. Fun for the whole family!

The effect is spectacular, sure. It’s probably not something you’d want to set up for every folder, though, because browsing is a pretty inefficient way to find something. But in folders containing photos or movies (that aren’t filled with hundreds of files), Cover Flow can be a handy and satisfying way to browse.

You can adjust the size of Cover Flow display(relative to the list-view half) by dragging up or down on the grip strip area just beneath the Cover Flow scroll bar.

Multipage PDF documents are special. When you point to one, circled arrow buttons appear on the jumbo icon. You can click them to page through the document—without even opening it for real (Figure 1-24).

QuickTime movies are special, too. When you point to its jumbo display, a

button appears. Click it to play the movie, right there in the Cover Flow window (Figure 1-23).

button appears. Click it to play the movie, right there in the Cover Flow window (Figure 1-23).You can navigate with the keyboard, too. Any icon that’s highlighted in the list view (bottom half of the window) is also front and center in the Cover Flow view. Therefore, you can use all the usual list-view shortcuts to navigate both at once. Use the up or down arrow keys, type the first few letters of an icon’s name, press Tab or Shift-Tab to highlight the next or previous icon alphabetically, and so on.

Cover Flow shows whatever the list view shows. If you expand a flippy triangle to reveal an indented list of what’s in a folder, the contents of that folder now become part of the cover flow.

The previews are actual icons. When you’re looking at a Cover Flow minidocument, you can drag it with your mouse—you’ve got the world’s biggest target—any where you’d like to drag it: another folder, the Trash, whatever.

As the preceding several thousand pages make clear, there are lots of ways to view and manage the seething mass of files and folders on a typical hard drive. Some of them actually let you see what’s in a document without having to open it—the Preview column in column view, the giant icons in Cover Flow, and so on.

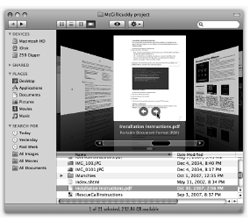

Quick Look, new in Leopard (and very welcome), takes this idea to another level. It lets you open and browse a document nearly at full size—without switching window views or opening any new programs. You highlight an icon (or several), and then do one of these things:

Press the Space bar. This is by far the best technique to learn. After all, unless you’re editing a file’s name, what’s the Space bar ever done for you in the Finder? Nothing. But in Mac OS X Leopard, you can highlight any icon and then tap the Space bar for an instant preview.

Press ⌘-Y. Another keystroke for the same function. The Space bar is still better, though.

Click the eyeball icon at the top of the window. If you don’t see the big eyeball icon, you probably upgraded your Mac from an earlier version of Mac OS X. But you can add the eyeball to the toolbar easily enough, as described on Apple’s toolbar-icon collection.

Choose Quick Look from the Action menu (

) at the top of every Finder window.

) at the top of every Finder window.Control-click (or right-click) an icon; from the shortcut menu, choose Quick Look.

You exit Quick Look in any one of these same ways.

Note

Whenever Quick Look appears in a menu or a shortcut menu, its wording changes to reflect the name of the icon. For example, it might say, "Quick Look ‘Secret Diary.doc.’”

In any case, the Quick Look window now opens, showing a nearly full-size preview of the document (Figure 1-25). Rather nice, eh?

Figure 1-25. Once the Quick Look window is open, you can play the file (movies and sounds), study it in more detail (most kinds of graphics files), or even read it (PDF, Word, and Excel documents). You can also click another icon, and another, and another, without ever closing the preview; the contents of the window simply change to reflect whatever you’ve just clicked. Supertip: Quick Look even works on icons in the Trash, too, so you can figure out what something is before you nuke it forever.

The idea here is that you can check out a document without having to wait for it to open in the traditional way. For example, you can find out what’s in a Word, Excel, or PowerPoint document without actually having to open Word, Excel, or PowerPoint, which saves you about 45 minutes.

You might wonder: How, exactly, is Quick Look able to display the contents of a document without opening it? Wouldn’t it have to somehow understand the internal file format of that document type?

Exactly. And that’s why Quick Look doesn’t recognize all documents. If you try to preview, for example, a Final Cut Pro video project, a sheet-music file, a .zip archive, or a database file, all you’ll see is a six-inch-tall version of its generic icon. You won’t see what’s inside.

Over time, Apple expects that the makers of those nonrecognized programs will develop plug-ins that teach Quick Look how to peek inside those documents. In the meantime, here’s what Quick Look recognizes right out of the box:

Graphics files and photos.This is where Quick Look can really shine, because it’s often useful to get a quick look at a photo without having to haul iPhoto or Photoshop out of bed. Quick Look recognizes all common graphics formats, including TIFF, JPEG, GIF, PNG, RAW, and Photoshop documents.

PDF and text files.Using the scroll bar, you can page through multipage documents, right there in the Quick Look window.

Audio and movie files.They begin to play instantly when you open them into the Quick Look window. Most popular formats are recognized (MP3, AIFF, AAC, MPEG4, H.264, and so on). A scroll bar appears so that you can jump around in the movie or song.

Microsoft Word,Excel,and PowerPoint documents.Because these formats are so common, Mac OS X comes with a Quick Look plug-in to recognize them. Move through the pages using the vertical scroll bar; switch to a different Excel spreadsheet page using the Sheet tabs at the bottom.

Fonts. Totally cool. When you open a font file in Quick Look, you get a crystalclear, huge sampler that shows every letter of the alphabet in that typeface.

vCards. A vCard is an address-book entry that people can send by email to each other to save time in updating their Rolodexes. When you drag a name out of Apple’s or Microsoft’s address books and onto the desktop, for example, it turns into a vCard document. In Quick Look, the vCard opens up as a handsomely formatted index card that displays all of the person’s contact information.

Pages,Numbers,Keynote,and TextEdit documents. Naturally, since these are Apple programs, Quick Look understands the document formats.

HTML (Web pages). If you’ve saved some Web pages to your hard drive, here’s a great way to inspect them without firing up your Web browser.

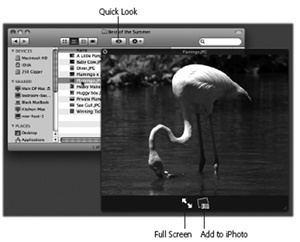

Here are some stunts that make Quick Look even more interesting.

Zoom in or out. Option-click the preview to magnify it; drag inside the zoomedin image to scroll; Shift-Option-click to zoom back out. Or press Option as you turn your mouse’s scroll wheel. (PDF documents have their own zoom in/zoom out keystrokes: ⌘-plus and ⌘-minus.)

Full screen. When you click the Full Screen arrows(identified in Figure 1-25),your screen goes black, and the Quick Look window expands to fill it. Keep this trick in mind when you’re trying to read Word, Excel, or PDF documents, since the text is usually too small to read otherwise. (When you’re finished with the closeup, click the Full Screen button again to restore the original Quick Look window, or the

button to exit Quick Look altogether.)

button to exit Quick Look altogether.)

Tip

How’s this for an undocumented shortcut?

If you Option-click the eyeball icon in any Finder window, you go straight into Full Screen mode without having to open the smaller Quick Look window first. Kewl.

Add to iPhoto. This icon appears in the Quick Look windows of graphics files that you’re examining. Click it to add the picture you’re studying to your iPhoto photo collection.

Keep it going. Once you’ve opened Quick Look for one icon, you don’t have to close it before inspecting another icon.Just keep clicking differenticons; the Quick Look window changes instantly with each click to reflect the new document.

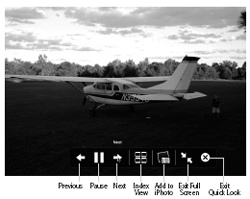

Mac OS X is supposed to be all about graphics and other visual delights. No wonder, then, that it offers a built-in, full-screen slideshow feature.

It works like this: Highlight a bunch of icons, and then open Quick Look. The screen goes black, and the documents begin their slideshow.Each image appears on the screen for about three seconds before the next one appears. (Press the Esc key or ⌘-period to end the show.) It’s like the Finder slideshow feature that debuted in Mac OS X 10.4, except that it plays all documents that it recognizes, not just graphics.

It’s a useful enough feature when you’ve just downloaded or imported a bunch of photos or Office documents and want a quick look through them. Use the control bar shown in Figure 1-26 to manage the playback.