Chapter 4. Camera Meets Mac

The Ansel Adams part of your job is over. Your digital camera is brimming with photos. You’ve snapped the perfect graduation portrait, captured that jaw-dropping sunset over the Pacific, or compiled an unforgettable photo essay of your two-year-old attempting to eat a bowl of spaghetti. It’s time to use your Mac to gather, organize, and tweak all these photos so you can share them with the rest of the world.

This is the core of this book—compiling, organizing, and adjusting your pictures using iPhoto, and then transforming this random collection of digital photos into a professional-looking slideshow, set of prints, movie, Web page, poster, email, desktop picture set, or bound book.

But before you start organizing and publishing these pictures using iPhoto, they have to find their way from your camera to the Mac. This chapter explains how to get pictures from camera to computer and introduces you to iPhoto.

iPhoto: The Application

iPhoto approaches digital photo management as a four-step process:

Import. Working with iPhoto begins with feeding your digital pictures into the program, either from a camera or from somewhere else on your Mac.

In general, importing is literally a one-click process. This is the part of iPhoto covered in this chapter.

Organize. This step is about sorting and categorizing your chaotic jumble of pictures so you can easily find them and arrange them into logical groups. You can add searchable keywords like Vacation or Kids to make pictures easier to find. You can change the order of images, and group them into “folders” called albums. As a result, instead of having 94,300 randomly named digital photos scattered about on your three hard drives, you end up with a set of neatly categorized and immediately accessible photo collections. Chapter 5 covers all of iPhoto’s organization tools.

Edit. This is where you fine-tune your photos to make them look as good as possible. iPhoto provides everything you need for rotating, retouching, resizing, cropping, color-balancing, straightening, and brightening your pictures. (More significant image adjustments—like editing out an ex-spouse—require another image-editing program.) Editing your photos is the focus of Chapter 6.

Share. iPhoto’s best features have to do with sharing your photos, either onscreen or on paper. In fact, iPhoto offers nine different ways of publishing your pictures. In addition to printing pictures on your own printer (in a variety of interesting layouts and book styles), you can display images as an onscreen slideshow, turn the slideshow into a QuickTime movie, order professional-quality prints or a professionally bound book, email them, apply one to your desktop as a desktop backdrop, select a batch to become your Mac OS X screen saver, post them online as a Web page, or “photocast” them (make them available to your fans’ copies of iPhoto 6, directly from your copy across the Internet).

Chapters 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 through 12 explain how to undertake these self-publishing tasks.

Note

Although much of this book is focused on using digital cameras, remember this: You don’t have to shoot digital photos to use iPhoto. You can just as easily use it to organize and publish pictures you’ve shot with a traditional film camera and then digitized using a scanner (or had Kodak convert them to a Photo CD). Importing scanned photos is covered later in this chapter.

iPhoto Requirements

According to Apple, iPhoto 6 requires a Mac that has a USB (Universal Serial Bus) port, a G3 chip or better, 256 MB of memory or more, and either Mac OS X 10.3.9 or, if you’ve upgraded to Tiger, 10.4.3 or later. (A faster chip is required for some editing functions and burning slideshows to DVD.)

Tip

The USB port makes it possible to connect a camera or memory card reader for directly importing the photos. But technically, you don’t need a USB port, since you can always import photos from the hard drive or a CD, as described later in this chapter.

The truth is, iPhoto may be among the most memory-dependent programs on your Mac. It just loves memory. Memory is even more important to iPhoto than your Mac’s processor speed. It makes the difference between tolerable speed and sluggishness, or between a 25,000-photo collection and a 250,000-photo collection. So the more memory and horsepower your Mac has, the happier you’ll be.

Finally, take a look at how much free hard drive space you have. You need at least 300 MB if you’re installing only iPhoto, iMovie, and iTunes. If you want iDVD and GarageBand too, iLife will eat up 10 GB of disk space—not including the room you’ll need for all your photos.

Getting iPhoto

A free version of iPhoto has been included on every Mac sold since January 2002. If your Mac falls into that category, you’ll find iPhoto in your Applications folder. (You can tell which version you have by single-clicking its icon and then choosing File → Get Info. In the resulting info window, you’ll see the version number clear as day.)

If you bought your Mac after January 2006, you probably have iPhoto 6 installed. Otherwise, it’s available only as part of Apple’s iLife ’06 software suite—an $80 DVD that includes GarageBand, iTunes, iMovie HD, iPhoto, iDVD, and iWeb. You can get the iLife box from www.apple.com/store, mail-order Web sites, or local computer stores.

When you run the iLife installer, you’re offered a choice of programs to install. Install all five programs, if you like, or just iPhoto.

When the installation process is over, you’ll find the iPhoto icon in your Applications folder. (In the Finder, choose Go → Applications, or press Shift-⌘-A, to open this folder.) You’ll also find the iPhoto icon—the little camera superimposed on the palm tree—preinstalled in your Dock, so you’ll be able to open it more conveniently from now on.

Upgrading from earlier versions

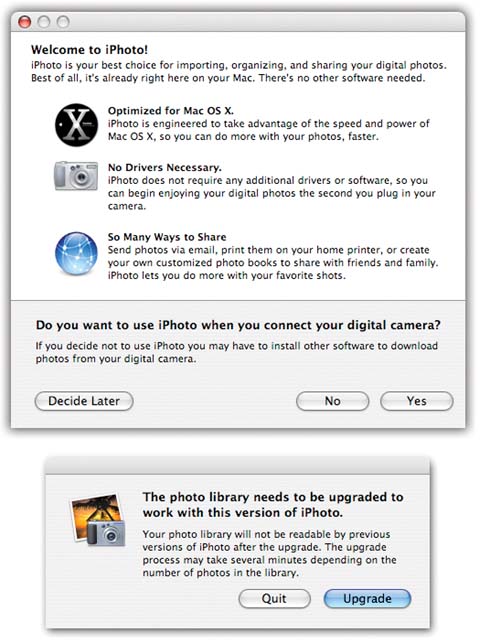

If you’ve used an earlier version of iPhoto, you’d be wise to make a backup of your iPhoto Library folder—your database of photos—before running iPhoto 6. That’s because iPhoto 6’s first bit of business is converting that library into a new, more efficient format that’s incompatible with earlier iPhotos (see Figure 4-1, bottom).

Ordinarily, the upgrade process is seamless: iPhoto smoothly converts and displays your existing photos, comments, titles, and albums. But lightning does strike, fuses do blow, and the technology gods have a cruel sense of humor—so making a backup copy before iPhoto 6 converts your old library is very, very smart.

To perform this safety measure, open your Home → Pictures folder, and then copy or duplicate the iPhoto Library folder. (This folder may be huge, since it contains copies of all the photos you’ve imported into iPhoto. This is a solid argument for copying it onto a second hard drive, like an iPod, or a burnable DVD.) Now, if anything should go wrong with the conversion process, you’ll still have a clean, uncorrupted copy of your iPhoto Library files.

Running iPhoto 6 for the First Time

Double-click the iPhoto icon to open the program. After you dismiss the “Welcome to iPhoto” dialog box (Figure 4-1, top), iPhoto checks to see if you have an older version and, if so, offers to convert its photo library (Figure 4-1, bottom).

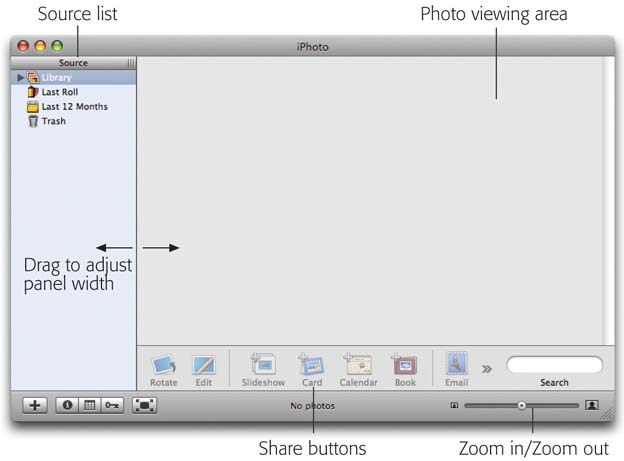

Finally, you arrive at the program’s main window, the basic elements of which are shown in Figure 4-2.

Getting Your Pictures into iPhoto

With iPhoto installed and ready to run, it’s time for you to import your own pictures into the program—a process that’s remarkably easy, especially if your photos are going directly from your camera into iPhoto.

Of course, if you’ve been taking digital photos for some time, you probably have a lot of photo files already crammed into folders on your hard drive or on Zip disks or CDs. If you shoot pictures with a traditional film camera and use a scanner to digitize them, you’ve probably got piles of JPEG or TIFF images stashed away on disk already, waiting to be cataloged using iPhoto.

This section explains how to transfer files into iPhoto from each of these sources.

Connecting with a USB Camera

Every modern digital camera can connect to a Mac using the USB port. If your Mac has more than one USB jack, any of them will do.

Plugging a USB-compatible camera into your Mac is the easiest way to transfer pictures from your camera into iPhoto.

Note

A few cameras require a pre-step right about here: turning the Mode dial on the top to whatever tiny symbol means “computer connection.” If yours does, do that.

The whole process practically happens by itself:

Connect the camera to one of your Mac’s USB jacks. Turn the camera on.

To make this camera-to-Mac USB connection, you need what is usually called an A-to-B USB cable; your camera probably came with one. The “A” end—the part you plug into your camera—has a small, flat-bottomed plug whose shape varies by manufacturer. The Mac end of the cable has a larger, flatter, rectangular, standard USB plug. Make sure both ends of the cable are plugged in firmly.

If iPhoto isn’t already running when you make this connection, the program opens and springs into action as soon as you switch on the camera. (It does, that is, unless you’ve changed the factory settings in Image Capture, a little program that sits in your Applications folder.)

Note

If this is the first time you’ve ever run iPhoto, it asks if you always want it to run when you plug in the camera. If you value your time, say yes.

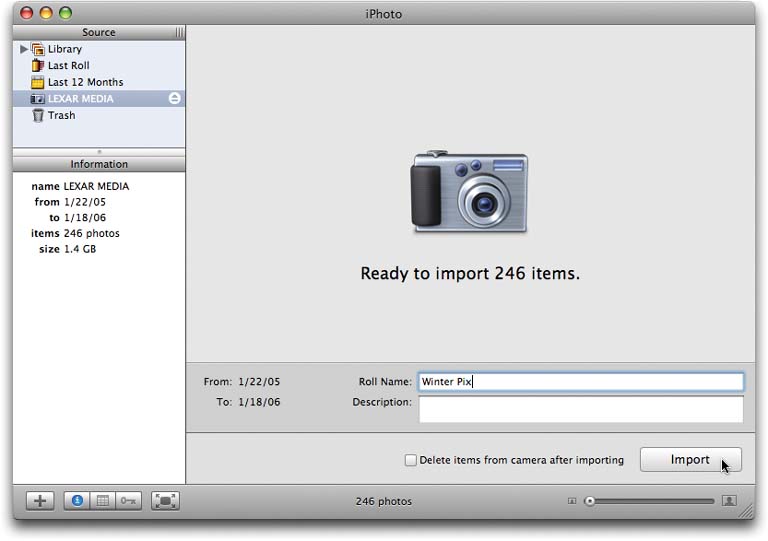

In iPhoto 6, there’s no wondering whether iPhoto is ready to do its job; the entire screen changes to show you the “ready” message shown in Figure 4-3.

Tip

If, for some reason, iPhoto doesn’t “see” your camera after you connect it, try turning the camera off, then on again.

In addition, your camera’s icon appears in the Source list. That’s handy, because it means that you can switch back and forth between the importing mode (click the camera’s icon) and the regular working-in-iPhoto mode (click any other icon in the Source list), even while the time-consuming importing is under way.

(Incidentally, as long as the camera’s appearing in the Source list—wouldn’t it be cool if you could drag photos onto the camera too? Maybe next year.)

If you like, type in a roll name and description for the pictures you’re about to import.

Each time you import a new set of photos into iPhoto—whether from your hard drive, a camera, or a memory card—that batch of imported photos is called a film roll.

Of course, there’s no real film in digital photography, and your pictures aren’t on a “roll” of anything. But if you think about it, the metaphor makes sense. Just as in traditional photography, where each batch of photos you shoot is captured on a separate roll of film, each separate batch of photos you download into iPhoto gets classified as its own film roll.

You’ll learn much more about film rolls in Chapter 5. For the moment, typing in a name for each new batch—Disney, First Weekend or Baby Meets Lasagna, for example—will help you organize and find your pictures later. (Use the Description box for more elaborate textual blurbs, if you like. You could specify the date, who was on the trip, the circumstances of the shoot, and so on.)

Turn on " Delete items from camera after importing,” if you like.

If you turn on this box, iPhoto will erase your camera’s memory card once the pictures and movies are safely on the Mac. The memory card will be all ready for another exciting photo safari.

Figure 4-3. iPhoto is ready to import, captain! If you have to wait a long time for this screen to appear, it’s because you’ve got a lot of pictures on your camera, and it takes iPhoto a while to count them up and prepare for the task at hand. (The number may be somewhat larger than you expect if you forgot to erase your last batch of photos.)Now, iPhoto won’t delete your pictures until after it has successfully copied them all to the Photo Library. However, it’s not beyond the realm of possibility that a hard disk could fail during an iPhoto import, or that a file could get corrupted when copied, thereby becoming unopenable. If you want to play it safe, leave the “Delete items from camera after importing” option turned off.

Then, after you’ve confirmed that all of your photos have been copied safely, you can use the camera’s own menus to erase its memory card.

Click the Import button.

If you chose the auto-erase feature, you’ll see a final “Confirm Move” dialog box, affording you one last chance to back out of that decision. Click Delete Originals if you’re sure you want the camera erased after the transfer, or Keep Originals if you want iPhoto to import copies of them, leaving the originals on the camera.

A different message appears if you’re about to import photos you’ve already imported (see Figure 4-4, top).

In any case, iPhoto swings into action, copying each photo from your camera to your hard drive. You get to see them as they parade by (Figure 4-4, bottom).

Figure 4-4. Top: If you’re not in the habit of using the “Delete items from camera after importing” option, you may occasionally see the “Import duplicates?” message. iPhoto notices the arrival of duplicates and offers you the option of downloading them again, resulting in duplicates on your Mac, or ignoring them and importing only the new photos from your camera. The latter option can save you a lot of time. Bottom: A nice feature in iPhoto 6: As the pictures get slurped into your Mac, iPhoto shows them to you, nice and big, as a sort of slideshow. You can see right away which ones were your hits, which were the misses, and which you’ll want to delete the instant the importing process is complete.When the process is over, your freshly imported photos appear in the main iPhoto window, awaiting your organizational talents.

“Eject” the camera by clicking the

button next to its name in the Source list.

button next to its name in the Source list.Or, if the

button doesn’t appear, just drag the camera’s icon directly downward onto the Trash icon. You’re not actually throwing the camera away, of course, or even the photos on it—you’re just saying, “Eject this.” Even if the camera’s still attached to your Mac, its icon disappears

from the Source list.

button doesn’t appear, just drag the camera’s icon directly downward onto the Trash icon. You’re not actually throwing the camera away, of course, or even the photos on it—you’re just saying, “Eject this.” Even if the camera’s still attached to your Mac, its icon disappears

from the Source list.Turn off the camera, and then unplug it from the USB cable.

You’re ready to start having fun with your new pictures (Section 4.3).

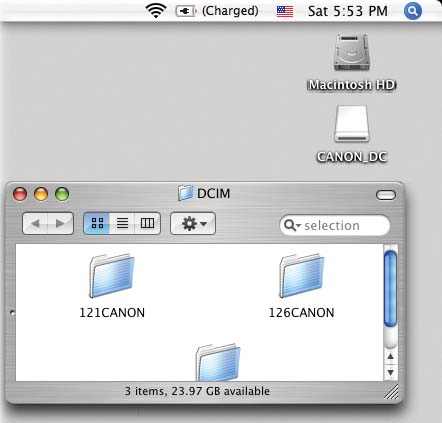

USB Card Readers

A USB memory card reader offers another convenient way to transfer photos into iPhoto. Most of these card readers, which look like tiny disk drives, are under $20, and some can even read more than one kind of memory card.

If you have a reader, then instead of connecting the camera to the Mac, simply remove the camera’s memory card and insert it into the reader (which you can leave permanently connected to the Mac). iPhoto recognizes the reader as though it’s a camera and offers to import (and erase) the photos, just as described on the previous pages.

This method offers several advantages over the camera-connection method. First, it eliminates the battery drain involved in pumping the photos straight off the camera. Second, it’s less hassle to pull a memory card out of your camera and slip it into your card reader (which is always plugged in) than it is to constantly plug and unplug camera cables. Finally, this method lets you use almost any digital camera with iPhoto, even those too old to include a USB cable connector.

Tip

iPhoto doesn’t recognize most camcorders, even though most models can take still pictures. Many camcorders store their stills on a memory card just as digital cameras do, so a memory card reader is exactly what you need to get those pictures into iPhoto.

Connecting with a USB-compatible memory card reader is almost identical to connecting a camera. Here’s how:

Pop a memory card out of your camera and insert it into the reader.

Of course, the card reader should already be plugged into the Mac’s USB jack.

As when you connect a camera, iPhoto acknowledges the presence of the memory card reader. A huge camera icon appears in the main window, you see the number of images on the card, and you’re offered a chance to type in a roll name and description. As described in Section 4.2.1, you can also turn on the “Delete items from camera after importing” checkbox if you want iPhoto to automatically clear the memory card after copying the files to your Mac.

Click Import.

iPhoto swings into action, copying the photos off the card.

Click the Eject button (

) next to the card’s name in the Source list, and then remove the card from the reader.

) next to the card’s name in the Source list, and then remove the card from the reader.Put the card back into the camera, so it’s ready for more action.

Importing Photos from Really Old Cameras

If your camera doesn’t have a USB connection and you don’t have a memory card reader, you’re still not out of luck.

First, copy the photos from your camera/memory card onto your hard drive (or other disk) using whatever software or hardware came with your camera. Then bring them into iPhoto as you would any other graphics files.

Importing Existing Graphics Files

iPhoto is also delighted to help you organize digital photos—or any other kinds of graphics files—that are already on your computer, like in a folder somewhere.

In fact, if that’s your situation, you’ve just stumbled onto one of the most profound new features in iPhoto 6.

For years, Mac fans complained about the way iPhoto handled photos that were already on the hard drive: when you imported them into iPhoto, the program duplicated them. You wound up with one set inside iPhoto’s proprietary library folder (Section 4.4) in addition to the original folder full of photos. Disk space got eaten up rather quickly as a result. This system also meant that iPhoto couldn’t simultaneously track photos that resided on more than one hard drive.

But now, for the first time in history, iPhoto can track, organize, edit, and process photos on your hard drive(s) right in place, right in the folders that contain them. The program doesn’t have to copy them into the iPhoto Library folder, doesn’t have to double their disk-space consumption.

This is a great blessing to people who already have folders filled with photos. You can drag them directly into iPhoto’s Source list (or the main viewing area). iPhoto acts like it’s importing them, but doesn’t really. Yet you can work with them exactly like the ones that iPhoto has actually socked away in its own library.

If you choose to go this route, here are a few tips and notes:

Very ugly things will happen in iPhoto if you delete a photo “behind its back,” in the Finder. When, in iPhoto, you try to open or edit one of the moved photos, an error message will appear, offering you the chance to locate the photo manually. And if you can’t find it, the photo opens up as a huge, empty, gray rectangle filled with an exclamation point. (You kind of know what the program means.)

On the other hand, iPhoto is pretty smart if you rename a photo in the Finder, or even drag it to a different folder. Apple doesn’t really want this feature publicized, hopes you won’t try it, and won’t say how iPhoto manages to track pictures that you move around even when the program isn’t running. But it works. Moved or renamed photos still appear in iPhoto, and you can still open, edit, and export them.

If you delete a photo within iPhoto, you’re not actually deleting it from your Mac. It’s still sitting there in the Finder, in the folder where it’s always been. You’ve just told iPhoto not to track that photo any more.

Using this feature, you can use iPhoto to catalog and edit photos that reside on multiple hard drives—even other computers on the network. Just make sure those other disks are “mounted” (visible on your screen) before you attempt to work with them in iPhoto.

On the other hand, iPhoto’s new offline smarts do not make it a good choice for managing photos on CDs, DVDs, or other disks that aren’t actually connected to, or inserted in, the Mac.

Internal or External?

Now, it’s nice that iPhoto can track external photos without having to slurp in its own private copies. But the old way had some advantages, too. When iPhoto copies photos into its own library, they’re safer. For example, you can back up your iPhoto Library folder, content in the knowledge that you’ve really backed up all your photos (instead of leaving some behind because they’re not actually in the Library folder).

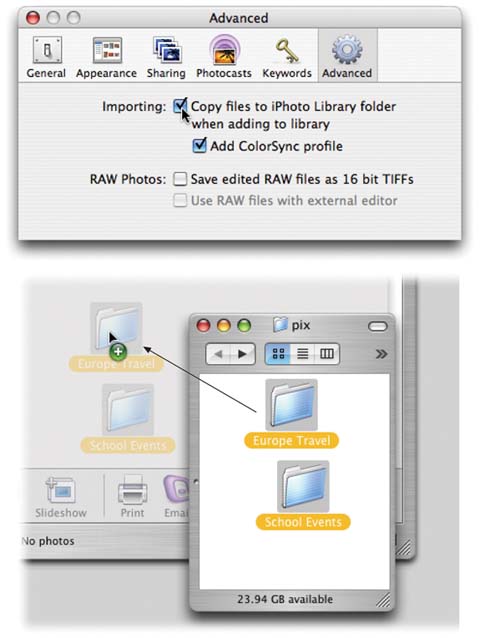

Fortunately, how iPhoto behaves when you import graphics files is entirely up to you. It can either copy them into its own Library folder, or it can track photos in whatever Finder folders they’re already in. You make this choice in the iPhoto → Preferences dialog box (see Figure 4-5, top).

Dragging into iPhoto

No matter what choice you make in the Preferences dialog box, the easiest way to import photos from your hard drive is to drag them into the main iPhoto window. You can choose from two methods:

Drag the files directly into the main iPhoto window, which automatically starts the import process. You can also drop an entire folder of images into iPhoto to import the contents of the whole folder, as shown in Figure 4-5 (bottom).

You can even drag a bunch of folders at once.

Tip

Take the time to name your folders intelligently before dragging them into iPhoto, because the program retains their names. If you drag a folder directly into the main photo area, you get a new film roll named for the folder; if you drag the folder into the Source list at the left side of the screen, you get a new album named for the folder. And if there are folders inside folders, they, too, become new film rolls and albums. Details on all this reside in Chapter 5.

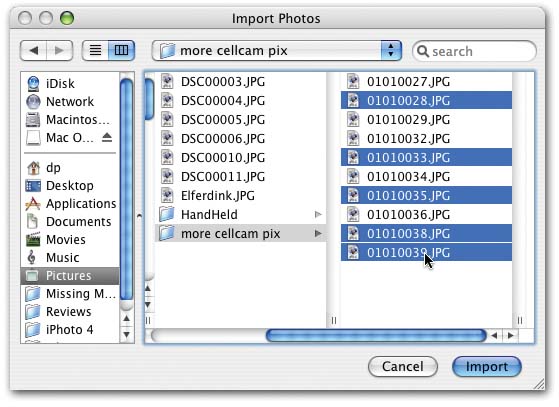

Choose File → Import to Library (or press Shift-⌘-I) in iPhoto and select a file or folder in the Open dialog box, shown in Figure 4-6.

These techniques also let you select and import files from other hard drives, CDs, DVDs, Jaz or Zip disks, or other disks on the network.

If your photos are on a Kodak Photo CD, you can insert the CD (with iPhoto already running), and then click the Import button on the Import pane, just as if you were importing photos from a connected camera. iPhoto makes fresh copies of the files you import, storing them in one centralized photo repository (the iPhoto Library folder) on your hard drive. The program also creates thumbnail versions of each image for display in the main iPhoto window.

The File Format Factor

iPhoto can’t import digital pictures unless it understands their file format, but that rarely poses a problem. Just about every digital camera on earth saves photos as JPEG files—and iPhoto handles this format beautifully. (JPEG is the world’s most popular file format for photos, because even though it’s compressed to occupy a lot less disk space, the visual quality is still very high.)

Note

While most digital photos you work with are probably JPEG files, they’re not always called JPEG files. You may also see JPEG referred to as JFIF (JPEG File Interchange Format). Bottom line: The terms JPEG, JFIF, JPEG JFIF, and JPEG 2000 all mean the same thing.

But there’s more to this story—in iPhoto 6, much more. The program now imports and recognizes some very useful additional formats.

RAW format

Most digital cameras work like this: When you squeeze the shutter button, the camera studies the data picked up by its sensors. The circuitry then makes decisions pertaining to sharpening level, contrast and saturation settings, color “temperature,” white balance, and so on—and then saves the resulting processed image as a compressed JPEG file on your memory card.

For millions of people, the resulting picture quality is just fine, even terrific. But all that in-camera processing drives professional shutterbugs nuts. They’d much rather preserve every last iota of original picture information, no matter how huge the resulting file on the memory card—and then process the file by hand once it’s been safely transferred to the Mac, using a program like Photoshop.

That’s the idea behind the RAW file format, which is an option in many pricier digital cameras. (RAW stands for nothing in particular, and it’s usually written in all capital letters like that just to denote how imposing and important serious photographers think it is.)

A RAW image isn’t processed at all; it’s a complete record of all the data passed along by the camera’s sensors. As a result, each RAW photo takes up much more space on your memory card. For example, on a 6-megapixel camera, a JPEG photo is around 2 MB, but over 8 MB when saved as a RAW file. Most cameras take longer to store RAW photos on the card, too.

But for image-manipulation nerds, the beauty of RAW files is that once you open them up on the Mac, you can perform astounding acts of editing on them. You can actually change the lighting of the scene—retroactively! And you don’t lose a single speck of image quality along the way.

Until recently, most people used a program like Photoshop or Photoshop Elements to do this kind of editing. But amazingly enough, humble, cheap little iPhoto 6 can now edit RAW files, too. For details on editing RAW images, see Chapter 6.

Note

Not every camera offers an option to save your files in RAW format. And among those that do, not all are iPhoto compatible. Apple maintains a partial list of compatible cameras at http://www.apple.com/macosx/upgrade/cameras.html. (Why are only some cameras compatible? Because RAW is a concept, not a file format. Each camera company stores its photo data in a different way, so in fact, there are dozens of different file formats in the RAW world. Programs like iPhoto must be upgraded periodically to accommodate new camera models’ emerging flavors of RAW.)

Movies

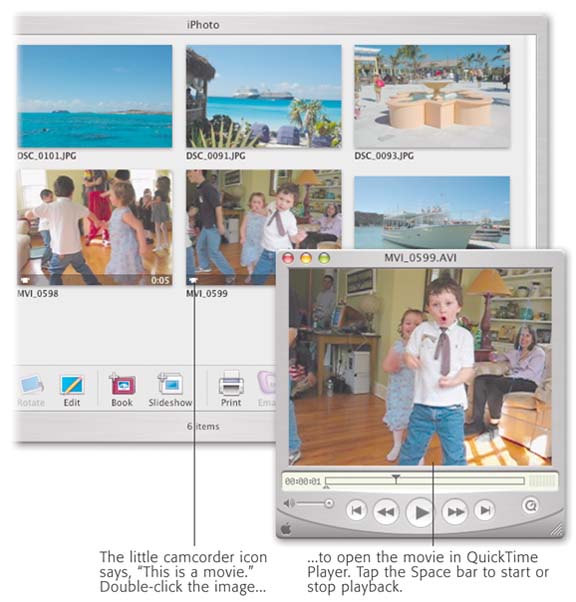

In addition to still photos, most consumer digital cameras these days can also capture cute little digital movies. Some are jittery, silent affairs the size of a Wheat Thin; others are full-blown, 30-frames-per-second, fill-your-screen movies (that eat up a memory card plenty fast). Either way, iPhoto can now import and organize them. The program recognizes .mov files, .avi files, and many other movie formats. In fact, it can import any format that QuickTime itself recognizes, which is a very long list indeed.

You don’t have to do anything special to import movies, since they get slurped in automatically. To play one of these movies once they’re in iPhoto, see Figure 4-7.

Other graphics formats

Of course, iPhoto also lets you load pictures that have been saved in a number of other file formats, too—including a few unusual ones. They include:

TIFF. Most digital cameras capture photos in a graphics-file format called JPEG. Some cameras, though, offer you the chance to leave your photos uncompressed on the camera, in what’s called TIFF format. These files are huge—in fact, you’ll be lucky if you can fit one TIFF file on the memory card that came with the camera. Fortunately, they retain 100 percent of the picture’s original quality.

Note, however, that the instant you edit a TIFF-format photo (Chapter 6), iPhoto converts it into JPEG.

That’s fine if you plan to order prints or a photo book (Chapter 10) from iPhoto, since JPEG files are required for those purposes. But if you took that once-in-a-lifetime, priceless shot as a TIFF file, don’t do any editing in iPhoto—don’t even rotate it—if you hope to maintain its perfect, pristine quality.

GIF is the most common format used for non-photographic images on Web pages. The borders, backgrounds, and logos you typically encounter on Web sites are usually GIF files—as well as 98 percent of those blinking, flashing banner ads that drive you insane.

PNG and FlashPix are also used in Web design, though not nearly as often as JPEG and GIF. They often display more complex graphic elements.

Figure 4-7. The first frame of each video clip shows up as though it’s a photo in your library; only a little camera icon and the total running time let you know that it’s a movie and not a photo. iPhoto is no iMovie, though; it can’t even play these video clips. If you double-click one, it actually opens up in QuickTime Player, a different program on your Mac that’s dedicated to playing digital movies. See Chapter 11 for details on editing these movies, either in iMovie or in QuickTime Player Pro.PICT was the original graphics file format of the Macintosh prior to Mac OS X. When you take a screenshot in Mac OS 9, paste a picture from the Clipboard, or copy an image from the Scrapbook, you’re using a PICT file.

Photoshop refers to Adobe Photoshop, the world’s most popular image-editing and photo-retouching program. iPhoto can even recognize and import layered Photoshop files—those in which different image adjustments or graphic elements are stored in sandwiched-together layers.

MacPaint is the ancient file format of Apple’s very first graphics program from the mid-1980s. No, you probably won’t be working with any MacPaint files in iPhoto, but isn’t it nice to know that if one of these old, black-and-white, 8 x 10 pictures, generated on a vintage Mac SE, happens to slip through a wormhole in the fabric of time and land on your desk, you’ll be ready?

SGI and Targa are specialized graphics formats used on high-end Silicon Graphics workstations and Truevision video-editing systems.

PDF files are Portable Document Format files that open up in Preview or Acrobat Reader. They can be user manuals, brochures, or Read Me files that you downloaded or received on a CD. Apple doesn’t publicize the fact that iPhoto can import PDF files, maybe because iPhoto displays only the first page of multipage documents. (Most of the PDFs you come across probably aren’t photos; they’re usually multipage documents filled with both text and graphics.)

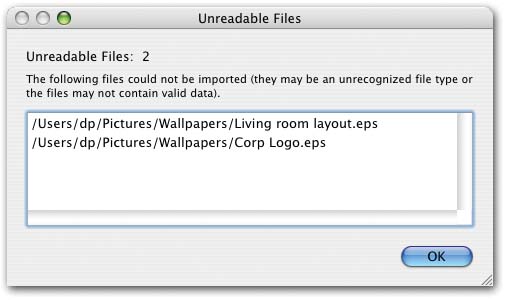

If you try to import a file that iPhoto doesn’t understand, you see the message shown in Figure 4-8.

The Post-Dump Slideshow

Once you’ve imported a batch of pictures into iPhoto, what’s the first thing you want to do? If you’re like most people, this is the first opportunity you have to see, at full-screen size, the masterpieces you and your camera created. That’s the beauty of iPhoto’s slideshow feature, which comes complete with the tools you need to perform an initial screen of the new pictures—like deleting the baddies, rotating the sideways ones, and identifying the best ones with star ratings.

To begin the slideshow, click the Last Roll icon in the Source list at the left side of the screen to identify which pictures you want to review.

Note

On a freshly installed copy of iPhoto, this icon is labeled Last Roll. If you’ve fiddled with the iPhoto preference settings, it may say, for example, “Last 2 Rolls” or “Last 3 Rolls,” and your slideshow will include more than the most recent batch of photos. If that’s not what you want to see, just click the actual photo that you want to begin the slideshow (in the main viewing area).

Now

Option-click the Play button (![]() ) at the bottom of the window. (If you don’t see it there, it’s probably been shoved off to the right by all the other tool icons. Click the >> button to see the word Play, or use the View → Show in Toolbar command to turn off the names of the tool icons you don’t use very often.)

) at the bottom of the window. (If you don’t see it there, it’s probably been shoved off to the right by all the other tool icons. Click the >> button to see the word Play, or use the View → Show in Toolbar command to turn off the names of the tool icons you don’t use very often.)

iPhoto fades out of view, and a big, brilliant, full-screen slideshow of the new photos begins, accompanied by music.

Tip

If you just click the Play button (instead of adding the Option key), you summon the Slideshow dialog box instead of starting the show. This dialog box has lots of useful options; for instance, you can choose the music for your slideshow. If you merely want a quick look at your new pix, however, Option-clicking is the way to bypass it.

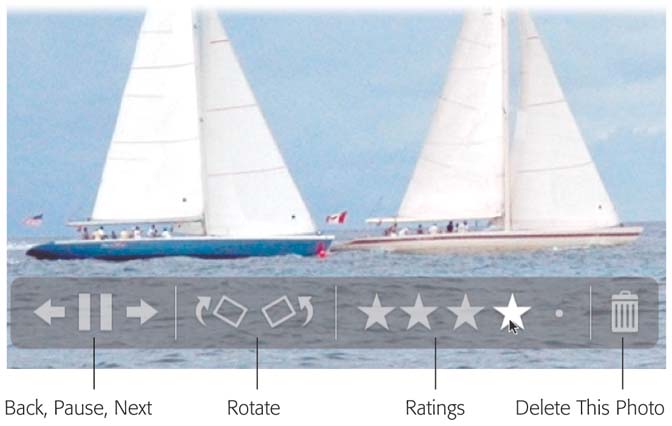

You can read more about slideshows in general in Chapter 7. What’s useful here, though, is the slideshow control bar shown in Figure 4-9. You make it appear by wiggling your mouse as the show begins.

This is the perfect opportunity to throw away lousy shots, fix the rotation, and linger on certain photos for more study—all without interrupting the slideshow. You can even apply a rating by clicking the appropriate star in the band of five; later, you can use these ratings to sort your pictures or create smart albums. See Chapter 5 for full detail on rating stars and smart albums.

Here’s the full list of things you can do when the onscreen control bar is visible:

Click the Play/Pause button to start and halt the slideshow. The space bar toggles these controls—and the control bar doesn’t have to be visible when you press it.

Click the left and right arrows to browse back and forth through your photos. The left and right arrow keys on your keyboard do the same thing.

Press the up or down arrow keys on your keyboard to make the slides appear faster or slower.

Click the rotation icons to flip photos clockwise or counterclockwise, 90 degrees at a time.

Click one of the five dots to apply a rating in stars, from one at the left to five all the way at the right. Or use the number keys at the top of the keyboard or on the numeric keypad; press 3 to give a picture three stars, for example.

Click the Trash can icon to delete a photo from the album you’re viewing (but not from the Photo Library). Or simply hit Delete (or Del) on your keyboard.

Tip

There are keyboard shortcuts for all of these functions, too, that don’t even require the control bar to be on the screen (Section 7.5).

Click the mouse somewhere else on the screen to end the slideshow.

Tip

You might want to use the new full-screen editing mode, rather than the slideshow mode, for your first post-dump look at the pictures (Section 5.5.3). It doesn’t advance the slides automatically, but it does offer far more editing power, plus handy thumbnails that let you see similar shots side-by-side.

Where iPhoto Keeps Your Files

Having entrusted your vast collection of digital photos to iPhoto, you may find yourself wondering, “Where’s iPhoto putting all those files, anyway?”

Most people slog through life, eyes to the road, without ever knowing the answer. After all, you can preview, open, edit, rotate, copy, export, and print all your photos right in iPhoto, without actually opening a folder or double-clicking a single JPEG file.

Even so, it’s worthwhile to know where iPhoto keeps your pictures on the hard drive. Armed with this information, you can keep those valuable files backed up and avoid the chance of accidentally throwing them away six months from now when you’re cleaning up your hard drive.

A Trip to the Library

Whenever you import pictures into iPhoto, the program makes copies of your photos, always leaving your original files untouched.

When you import from a camera, iPhoto leaves the photos right where they are on its memory card (unless you use the “Erase” option).

When you import from the hard drive into iPhoto, the originals remain in whichever folders they’re in. As a result, transferring photos from your hard drive into iPhoto more than doubles the amount of disk space they take up. In other words, importing 1 GB of photos requires an additional 1 GB of disk space, because you’ll end up with two copies of each file: the original, and iPhoto’s copy of the photo. In addition, iPhoto creates a separate thumbnail version of each picture, consuming about another 10 K to 20 K per photo.

iPhoto stores its copies of your pictures in a special folder called iPhoto Library, which you can find in your Home → Pictures folder. If the short name you use to log into Mac OS X is mozart, the full path to your iPhoto Library folder from the main hard drive window would be Macintosh HD → Users → mozart → Pictures → iPhoto Library.

Tip

You should back up this iPhoto Library folder regularly—using the Burn command to save it onto a CD or DVD, for example. After all, it contains all the photos you import into iPhoto, which, essentially, is your entire photography collection. Chapter 14 offers much more on this file management topic.

What all those numbers mean

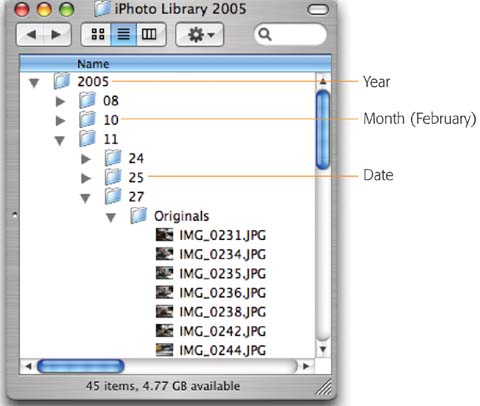

Within the iPhoto Library folder, you’ll find a set of mysteriously numbered files and folders. At first glance, this setup may look bizarre, but there’s a method to iPhoto’s madness. It turns out that iPhoto meticulously arranges your photos within these numbered folders according to the creation dates of the originals, as explained in Figure 4-10.

Other folders in the iPhoto Library

In addition to the numbered folders, you’ll find several other items nested in the iPhoto Library folder, most of which you can ignore:

AlbumData.xml. Here’s where iPhoto stores access permissions for the various photo albums you’ve created within iPhoto. (Albums, which are like folders for organizing photos, are described in Chapter 5.) For example, it’s where iPhoto keeps information on which albums are available for sharing across the network (or among accounts on a single machine). Details on sharing are in Chapter 9.

Dir.data, iPhoto.db, Library.data, Library6.iPhoto. These are iPhoto’s for-internal-use-only documents. They store information about your Photo Library, such as which keywords you’ve used, along with the image dimensions, file size, rating, and modification date for each photo.

Data. This folder contains index card-sized previews of your pictures—jumbo thumbnails, in effect—organized in the year/month/day structure shown in Figure 4-10.

Originals. This folder, reconceived in iPhoto 6, is the real deal: It’s the folder the stores your entire photo collection. Inside, you’ll find nested folders organized in the year/month/day structure illustrated in Figure 4-10.

This folder is also the key to one of iPhoto’s most remarkable features: the Revert to Original command.

Whenever it applies any potentially destructive operations to your photos—like cropping, red-eye removal, brightening, black-and-white conversion—iPhoto duplicates the files and stuffs the edited copies in the Modified folder. The pristine, unedited versions remain safely in the Originals folder. If you later decide to scrap your changes to a photo using the Revert to Original command—even months or years later—iPhoto ditches the duplicate. What you see in iPhoto is the Original version, preserved in its originally imported state.

Modified. Here are the latest versions of your pictures, as edited. (Remember, behind the scenes, iPhoto actually duplicates a photo when you edit it.)

Look, don’t touch

While it’s enlightening to wander through the iPhoto Library folder to see how iPhoto keeps itself organized, don’t rename or move any of the folders or files in it. Making such changes will confuse iPhoto to the point where it will either be unable to display some of your photos or it’ll just crash.

Get iPhoto 6: The Missing Manual, 5th Edition now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.