CHAPTER 3

TACTICS

T

he previous chapter described the foundation attributes on

which influence is built: trustworthiness, reliability, and an

assertive style of behavior and communication. Think of

these as prerequisites—as personal characteristics you must bring

to the table if you really want to get into the influence game. But

once you’re in the game, what then? What tactics can you employ

to influence other people in your organization? This is the question

we will answer in this chapter.

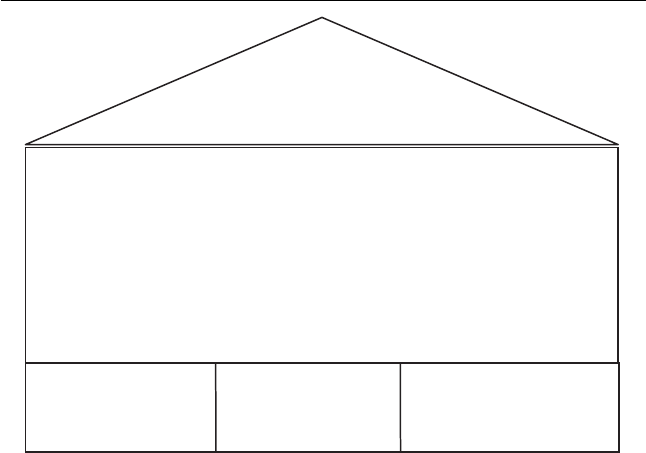

Figure 3-1 revisits the ‘‘structure of influence’’ concept intro-

duced in Chapter 2, adding six supporting tactics onto its founda-

tion of personal attributes:

1. Create reciprocal credits.

2. Be a source of expertise, information, and resources.

3. Help people find common ground.

4. Frame issues your way.

American Management Association

www.amanet.org

24 Increase Your Influence at Work

5. Build a network of support.

6. Employ persuasive communication.

Although this list of tactics is not complete, it includes those avail-

able to all readers. These are actions that anyone in any organiza-

tion can take to increase his or her influence.

CREATE RECIPROCAL CREDITS

Every society we know of honors the principle of reciprocity. Ac-

cording to this principle, if you do a favor for someone, that person

owes you a favor in return—and you have a right to expect it. Until

FIGURE 3-1. THE STRUCTURE OF INFLUENCE WITH

ITS SUPPORTING TACTICS.

Trustworthiness Reliability Assertiveness

INFLUENCE

Reciprocal credits Expertise-info-resources

Common ground Framing

Network of support Persuasion

American Management Association

www.amanet.org

Ta c t i c s 25

that favor is returned, you have a ‘‘credit’’ on the balance sheet of

your relationship with that other person. You might think of it as

an ‘‘account receivable’’—a value owed to you by someone else.

This principle of reciprocity operates in all sectors of human

affairs. Consider the world of politics. In the United States, most

organized interest groups—from corn growers to bankers to teach-

ers’ unions to green energy producers—have lobbyists in the na-

tion’s capital. These lobbyists have a common goal: to influence

legislation and policy in favor of their organizations or clients. Con-

tributing to reelection campaigns is one method used to gain in-

fluence. According to the Center for Responsive Politics, the

nation’s 15,138 registered lobbyists made political contributions of

$3.24 billion in 2008. That’s well over $5 million, on average, for

every senator and congressional representative in Washington.

Those contributions aim to support the reelection of politicians

friendly to the interests of lobbying organizations. However, for

recipients, those contributions create a sense of obligation to recip-

rocate in some way, such as giving contributing lobbyists opportu-

nities to be heard on legislative matters that affect their clients’

interests. As the old saying goes, he who pays the piper calls the

tune. And there’s plenty of evidence that contributors of campaign

funds do receive the access they seek.

Reciprocity operates in the workplace as well. Because his boss

was under pressure to make a presentation to top management

on Wednesday, Chuck spent part of his weekend developing her

PowerPoint slides. Credit Chuck’s account; his boss owes him.

Meanwhile, Chuck has asked the IT manager to fix a problem with

his PC. That’s the IT manager’s job, but because that manager

knocked herself out to solve the problem right away, Chuck owes

her something in return. Add that to Chuck’s accounts payable.

In their excellent book Influence Without Authority, Allan

American Management Association

www.amanet.org

26 Increase Your Influence at Work

Cohen and David Bradford note that ‘‘exchanges’’ like the ones just

described are commonplace in organizational life.

1

These ex-

changes occur between peers, between bosses and their subordi-

nates, and between company employees and outsiders such as

customers and suppliers. These exchanges may involve money, ser-

vices, resources, or information. And every exchange represents an

opportunity to create influence.

Take a moment to think about and write down the reciprocal

credits owed to you, and those you owe to others. Who are your

leading creditors and debtors? The principle of reciprocity provides

you with opportunities to create influence if you use them tacti-

cally. The following sections provide suggestions for making the

most of those opportunities.

Identify the People You Wish to Influence

You have only so many favors to do and resources to share, so

identify the people you most want to influence—the people who

can help you to be successful at work. Though it’s good policy to

be openhanded with everyone, scarcity of time and resources de-

mands that you prioritize your efforts.

Determine What They Value

The principle of reciprocity works only when the favor you do for

someone, or the resource you share, is truly valued by the other

party. In our previous example, how much does the boss value the

PowerPoint slides Chuck created for her over the weekend? Well, if

they made her look good to top management, we can assume that

the boss attached a high value to Chuck’s slides. You get the idea.

American Management Association

www.amanet.org

Get Increase Your Influence at Work now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.