CHAPTER 2

THE F OUNDATION OF INFLUENCE

N

ow that you under s ta nd the meani ng of influenc e and the re-

lated concepts of power and persuasion, we can move on to

prac ti c a l s te ps y ou c an take to enha nc e your influence at work.

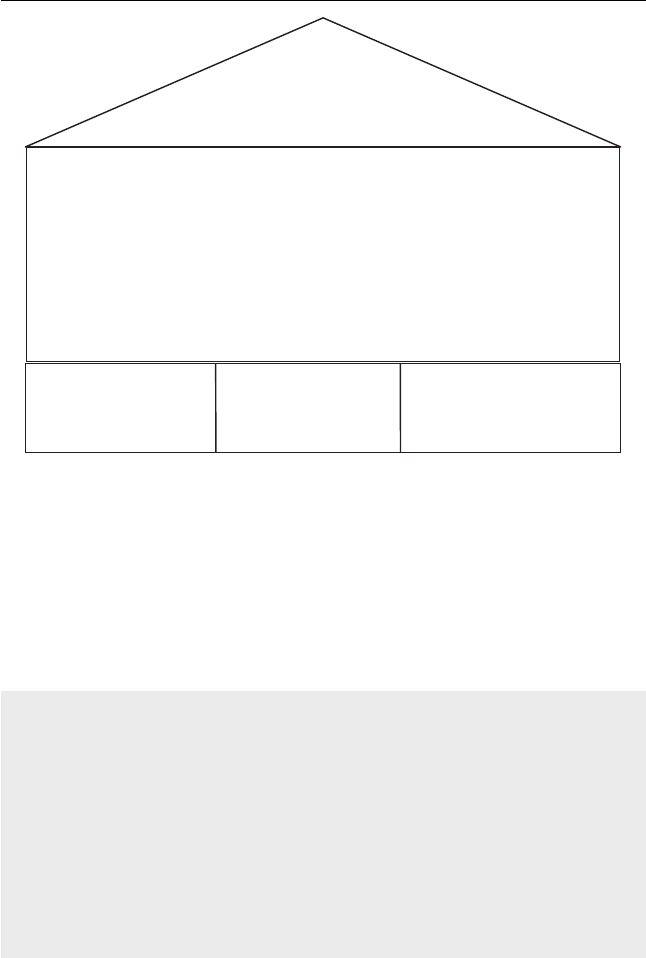

Conceptu all y, it’s useful to think of influence in terms of a struc-

ture built on a solid foundation of pers ona l attributes and supportive

tactics, as shown in Figure 2-1. The attributes are trustworthiness ,

reliabil ity, and assertiveness. These are personal attributes you can

develop over time and are the subjec ts of this chapter. Think of them

as the ‘‘ante ’’ the would-be influencer must pay to join the game.

In and of themselves these attributes will not give you substantial

influence, but you cannot be highly influential without them. To win

the game, you must employ one or more supporting tactics; you’ ll

learn about those in Chap ter 3.

American Management Association

www.amanet.org

The Foundation of Influence 11

FIGURE 2-1. THE STRUCTURE OF INFLUENCE.

Trustworthiness Reliability Assertiveness

Supporting Tactics

INFLUENCE

TRUSTWORTHINESS

It’s obvious that a person considered untrustworthy will have a

hard time influencing the decisions, behavior, or thinking of oth-

ers. This example makes it clear why:

Last year Jane lobbied heavily on behalf of a plan to create and

staff a new sales territory in the Minnesota-Wisconsin area. ‘‘It

should be profitable within two years,’’ she insisted. People

were interested because top management was pushing for

profit growth, and her plan supported that important goal. The

national sales manager became very excited and began talking

up Jane’s plan to his boss, the vice president of sales and mar-

keting. ‘‘Opening a small office in Madison, Wisconsin, with

American Management Association

www.amanet.org

12 Increase Your Influence at Work

three outside salespeople could contribute $2 million to corpo-

rate profitability if Jane is right,’’ he told his boss.

Interest in the plan evaporated, however, once it became

clear that Jane hadn’t taken the trouble to develop realistic

cost estimates for the expansion. They were simply off-the-

top-of-her-head guesses. Worse, her anticipated sales reve-

nues from the new territory were based on what everyone con-

sidered to be unrealistic assumptions. The national sales

manager was embarrassed by his initial enthusiasm, which had

reduced his credibility with his own boss. Consequently, the

next time Jane tried to promote a new idea, she was ignored.

Jane is a fictitious character, but her behavior is drawn from

that of people we’ve all met in the workplace at one time or an-

other. These are not bad people; they often have the best of inten-

tions. Unfortunately, their suggestions cannot be accepted at face

value because they don’t go to the trouble of checking their facts

and building a solid, supportable case. They fail the test of trust-

worthiness, with the result that they have little influence on others.

Consider what would happen if Jane had approached her case

for an expansion into the Minnesota-Wisconsin area in a very differ-

ent, more credible way—not off the top of her head, but based on

solid facts, analysis, and realistic assumptions. The risks in the plan

would have been identified, and where critical information was

lacking she would have said something like this: ‘‘At this point I

cannot offer a revenue estimate for the proposed new territory. We

do not know the total demand for our products in that region, or

how much of it our competitors are now getting. That information

must be obtained through market research before we invest in the

idea. I’ve begun talking with our market research staff about how

we can get those data.’’

American Management Association

www.amanet.org

Get Increase Your Influence at Work now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.