Chapter 1. Evaluating the Incident Response PROCESS

Definition of incident:

An occurrence, either human-caused or a natural phenomenon, that requires action or support by emergency services personnel to prevent or minimize loss of life or damage to property and/or natural resources. (National Fire Protection Association)

An unplanned interruption to an IT service or reduction in the quality of an IT service. (ITIL)

As you read this sentence, IT incidents are happening all over the world. The response to those incidents comes in many forms, from one person working on an issue to a large group of people dialing into a conference call bridge or typing into a plethora of communications/workflow/productivity applications from anywhere around the globe. Those responders may use ITIL process or DevOps principles or an internally created system or some other method. The response may be completely organized or totally chaotic. But, one way or another, IT incidents are being resolved. The real question is: “Are they being resolved as quickly as they could be?”

Note

For illustration throughout the book, we will use a conference call bridge as the example of IRT communications. There are many methods used to communicate during an incident, including verbal and written communications across many technology platforms, and not all IRTs use conference bridges for incident response, but depicting the spoken word serves as an effective platform to illustrate interpersonal communications.

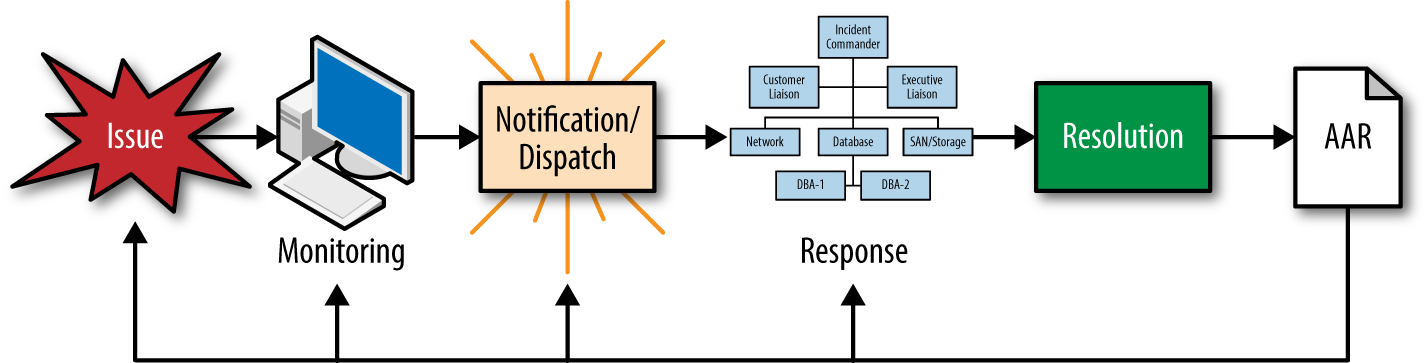

The first step in the journey toward efficient and well-organized incident response begins with an honest evaluation of the status quo, including the Incident Lifecycle (see Figure 1-1). In many cases, incident responders find their way into a pattern of responding (either good or bad) and end up sticking with it out of inertia. Some responders may have survived a significant incident and say “wow, that was a close call, hope that never happens again.” Patterns and habits, by their very nature, are comfortable to maintain and difficult to break.

Figure 1-1. The Incident Lifecycle

Regardless of whether you are happy or unhappy with the way your Incident Response Team (IRT) responds to IT emergencies, it is wise to investigate if performance can be improved.

Note

For the sake of consistency, the remainder of this book will use the term Incident Response Team (IRT) as a general term for the group tasked with mitigating incidents within an organization. Your particular group may have a different term or organizational structure for responding to incidents.

After all, incidents pose risk to the company in many ways, none of them good: tarnished reputation; erosion of customer trust; diminished brand; adverse financial impacts and loss of investor confidence. Successful and efficient Incident Response Teams share common characteristics, all of which are easy to identify once you know what to look for. Separate and apart from an After Action Review (AAR) (see Chapter 6), which takes place after the response, it may be useful for you to evaluate your entire incident response process as it exists today and see if there are areas that could be improved.

To begin, it is useful to develop a list of general questions that can be asked and answered both quantitatively and qualitatively. Having good baseline data on past response statistics and/or how your response team is set up helps lay the foundation for evaluation.

If you are a small organization with just a few people, it might seem obvious who will respond to resolve incidents. One of the first questions we ask organizations is this: Is there one person here who understands the entire stack in great detail to fix any issue that may occur? The obvious answer is no, but we have validated this with organizations around the world. Plus, as businesses grow and scale, the entire stack will continue to get more complicated, requiring more specialized problem solvers, which will require a more mature incident management process. If your organization acquires companies to expand its business and portfolio of products and services, incident management processes at the acquired companies should also be identified, evaluated, and reviewed during the due diligence phase of the deal. Irrespective of how your organization grows, ask yourself questions like the following to narrow your focus on how to best configure the Incident Response Team.

This list of questions is certainly not exhaustive and is meant to simply stimulate your own thinking about how to lay a foundation for an Incident Response Team evaluation:

-

What is your definition of an incident and event?

-

How many incidents do you respond to in a given month?

-

What is the ratio of incidents to events and do you respond the same way to both?

-

How many incidents occurred per month over the last two years?

-

How many events occurred per month over the last two years?

-

Identify and describe current severity/priority levels for incident response.

-

Are incident severity/priority levels used and/or consistently applied throughout the incident response organization?

-

What reports/data analysis regarding incident response do you have?

-

In your opinion, are incidents managed and directed in a consistent and efficient manner? If not, list the challenges/obstacles.

-

When an incident occurs, is there a defined plan for response and escalation?

-

Is there a core team with 24x7 on-duty responsibilities or is the team on call?

-

List all potential incident responders (Incident Commanders and SMEs) by business unit and geographic location.

-

Describe shift schedule and staffing levels for the primary Incident Response Team, by location and function.

-

List third-party vendors that are part of the incident response by function, location, and contact information.

-

Do IRT members have time standards for incident response? Are those time standards followed by responders and enforced by executive leadership?

-

What challenges exist in terms of integrating SMEs into a response?

-

Is there an organization chart for incident response that lists the primary Incident Response Team and all other participants?

-

How do communications occur during an incident (e.g., conference call, web-based tools, etc.)?

-

Are incident voice communications (e.g., conference bridges, WebEx, etc.) recorded? Archived? Reviewed?

-

Is someone assigned to prepare and conduct the Root Cause Analysis (RCA) and AARs?

-

Is there a process for incorporating information learned from AAR recommendations back into peacetime development/engineering?

-

What role do senior executives play during an incident response?

Keep in mind that efficient incident response is all about process, with ten general but distinct steps in the Incident Lifecycle:

-

Detect the issue.

-

Determine if issue is an incident or an event.

-

Dispatch the appropriate Incident Response Team.

-

Assemble the response team mean time to assemble (MTTA).

-

Establish command, organize resources, and set incident objectives.

-

Lead the resolution effort using IMS.

-

Notify the appropriate stakeholders.

-

Resolve the incident and release resources.

-

Conduct AARs.

-

Implement quality improvement (QI) and quality assurance (QA) (covered in more detail later in the chapter).

You might come across a version of this list in a different order or perhaps with a different step here or there, but, for the most part, this is how an IT incident evolves. Figure 1-1 depicts the Incident Lifecycle. QA and QI are part of the AAR process, and not called out as separate items here.

We commonly run into Incident Response Teams that have been overwhelmed by an incident that got bigger and/or nastier and/or moved faster than they were prepared for. Perhaps they could not assemble the right technical resources quickly or were frustrated by the fact that only a few members of the team were “capable of running an incident.” Or there may have been a lack of clear and directed leadership, resulting in chaos on the incident conference call bridge or some other communication channel. Successfully operating high-reliability, production environments depends on strong leadership and a capable team of technical experts in network, compute, storage, and applications, whether for a small DevOps team or a global enterprise team. In daily workflows, for example, DevOps is a team sport with a collaborative methodology that marches to a certain cadence. Incident response is also a team sport that depends on strong leadership and a capable team of technical experts, but the pace at which the team assembles and begins resolution is different than completing a sprint or some other nonincident-related task.

We’ve developed an acronym that represents the seven key attributes of an effective incident response program. PROCESS stands for Predictable, Repeatable, Optimized, Clear, Evaluated, Scalable, and Sustainable.

To that end, each letter of PROCESS is an interdependent link in the incident response chain. Use those links as a step-by-step analysis tool to evaluate how your current IT response approach measures up. The Incident Lifecycle is also a series of interrelated steps that builds progressively on the previous step and has influence on all the other downstream steps. As an example, if reducing your overall mean time to repair (MTTR) of an IT incident is important to the company, you must look at every element of the Incident Lifecycle, from detecting the presence of an issue, to how the team is dispatched and how long it takes to assemble the right team of people, all the way through the resolution effort and AAR.

Many companies waste valuable time early in the Incident Lifecycle due to inefficient dispatch of the responders. Additionally, we find many companies do not draw a clear distinction between a notification and a dispatch. It is typical to find no clear distinction between those who are “in the loop” of information regarding an incident and those who are called to respond.

Some companies use the “spray and pray” or “group think” approach of sending out notifications to a bunch of technical experts, executives, and others, having dozens of them arrive on an open conference call bridge (or other communications method) with no identified leader, with the hope the group will resolve the issue in a reasonable amount of time. In practice, these groups meander their way to resolution. In other cases, there is no clear expectation that once alerted, an incident responder must arrive on a conference call bridge with any sense of urgency. Many companies are quite lax when it comes to defining and communicating clear expectations about being “on-call.” If you are on-call, you are in the “right now” business, not the “I’ll get around to it in a few minutes” business, or “I’m busy doing other things” business. Time is money and the longer it takes to dispatch and assemble the right team, the longer it takes to resolve the issue. You can get more responders or write more code, but you can’t make any more time. Time can only be saved or wasted.

Many teams (and company executives) focus on asking about a Root Cause Analysis (RCA) of an issue in the first few minutes of an incident. This is the wrong question to ask. Asking “why it broke” (root cause) is far less important than “how do we fix it” (incident resolution). In our opinion, the first thing to focus on is the mean time to assemble (MTTA) the right team. You won’t have good MTTRs with slow MTTAs! In the early stages of an incident, facts are being discovered as the situation unfolds. The best fact discoverers are the right technical subject matter experts (SMEs) responding to the incident, because they can look at logs, perform queries, and run analytics. These SMEs become the eyes and ears of the Incident Response Team. Without urgent MTTA from SMEs, there is no data. Without data, the Incident Response Team is flying blind and corrective action can’t be taken. Focus on fixing the issue first and restoring service! As we say in the fire department, “when you put out the fire, conditions get better.”

To that end, be hard on yourself and your expectations, and be realistic when it comes to evaluating your current incident response process. There are easy pick-ups in MTTA in most companies if the company is willing to set clear expectations. Think about this: the MTTA part of the Incident Lifecycle contains all of the activities prior to response. MTTA is the only activity that is controlled by the Incident Response Team! Incident resolution is a wild card as your operating environment is complex and conditions of the incident can change at any moment. We’ll say it again for emphasis, MTTA is the only activity that is controlled by the Incident Response Team!

The answers that you find by using PROCESS as an evaluation template will differ from company to company, because a cookbook approach doesn’t exist. This is more of a thought exercise you can use to explore and map the various aspects of a PROCESS-driven Incident Response Team, and to discover and correct any weaknesses in your system along the way.

Predictable

The foundation of excellent Incident Response Teams is predictability. Customers buy and expect 7×24×365 availability from their service providers. We know that 100% availability is a near impossible metric, so companies aim for 99.99% or greater. In fact, enormous investments are made with each incremental 9 to the right of the availability decimal point, improving from 99.99% to 99.999%. So, if ultimate availability is elusive in production environments, predictability in incident response is absolutely essential.

Predictability in incident response is about clarity of roles and responsibilities and the expected behavior of each person before and after they are assembled for an incident. It’s about eliminating uncertainty in the assembly phase of the response. Are there clear expectations for which SMEs might be required for a particular incident type, and who will take the leadership role of the Incident Commander? Efficient Incident Response Teams, no matter how big or small, have crisp, well defined on-call procedures and they hold people accountable!

Are your technical experts on-call in different time zones? Are there back-ups to the primary on-call personnel? Are they clear that “on-call” means ready to respond to a page, text, or other notification in a time frame specified by the company?

Having responders understand their role is critical to success. Incident response isn’t about arriving to help resolve the issue when it’s convenient. If you are identified as available on-call, it is not optional. Perhaps your regular day job keeps you crazy busy every day. If you are on-duty or on-call as an identified incident responder, make sure you are ready to respond quickly. Be ready, willing, and able to answer the call and protect the business!

Ensuring that response expectations are clear is the low-hanging fruit because it can be done in advance of the incident occurring. Identifying the players, or at least the type of players you might need, is a pre-planning exercise and can be largely scripted in a defined response plan and evaluated/refined as part of the AAR. Think about your last 10 incidents and evaluate the MTTA in terms of getting the right people to the response. Did you get the right people to respond quickly and with a sense of urgency? Did they perform and participate in a positive way? If not, why not? Think of predictability as the “who” part of the response.

Repeatable

If there is uncertainty about who will respond to an incident and who will be in charge, and how you bring them together for a response, then your incident response can be improved.

Repeatability is the “how” part of the response, with the goal of consistently and efficiently dispatching the people identified in the predictability section. Highly efficient Incident Response Teams have reviewed a list of common or likely incident types, assigned each a severity (SEV) level, identified SMEs by function to respond and matched the dispatch of SME responders to those severity levels. For example, a SEV level 1 may have a predetermined list of technical expertise (network, compute, storage, applications) that would be appropriate for a particular incident type. Each organization is different, so we aren’t going to provide specific examples. Suffice it to say that timely identification of an IT incident, which drives a rapid and specific dispatch procedure with clear expectations about when and how the incident responders will convene (the quicker, the better) is the keystone to predictability. Repeatability demonstrates that every response to any type of incident should strive to be the same no matter what time of day, day of the week, or time of year it occurs. For example, predictable and repeatable responses should happen the same way at 2:00 A.M. on Christmas morning or 2:00 P.M. on any normal business day. Predictability and repeatability is the natural enemy of spray and pray!

This is not to say that an organization must have 24x7 operations to qualify for having a demonstrably repeatable response. It is more about the incident responders being truly available when they are designated to be on-call and responding in the same way every time.

Optimized

Optimization builds upon a predictable and repeatable incident response mechanism by ensuring the identified responders understand the rules of engagement during incidents and are trained, equipped, and clearly prepared to do what is being asked of them. Do you have a formal training program for responders (and we hope it’s based on IMS!)? Is it provided consistently across your team, especially if the team is global? Does everyone understand how they fit into the incident response? Are there clear escalation policies in place? What conditions must be present to trigger an escalation? Who gets the escalation?

If you interact with vendors or other third parties, do they know how to respond and participate? Do they share your same sense of urgency? Is the concept of incident command universally understood and implemented?

It’s easy to spot those individuals that just “don’t get it” in terms of having the sense of urgency and focus required to resolve an incident, or who feel inconvenienced by being on-call in the first place. However, was the importance of the incident response plan explained to them? Were they trained in their individual and team roles in incident response? Incident response is a team sport, and leaves no room for egos, attitude, or lack of trust within the team. It’s important to hold people accountable but it’s unfair if they are held accountable without ever being trained or briefed as to the company’s expectations. In our consulting practice, we emphasize the need to identify all the potential Incident Commanders, technical SME experts, executives, vendors, and any others who may be called to respond. This allows us to ensure that they all have specific incident response training and a clear understating of the expectations, so that at minimum each incident responder knows what is expected of them and are prepared to contribute appropriately. Predictability is the who and repeatability is the how of incident response. Optimization is the part of PROCESS where you must ensure that everyone is trained and equipped to do the job!

Clear

Clarity ensures that general programmatic and incident response goals and objectives are conveyed to all IRT members and all others that may participate in a response. It’s easy to assume that all who might join an incident response in any capacity are clear about the goals and objectives of the incident resolution effort. Unfortunately, this isn’t always the case. Oftentimes, we find that IT responders aren’t clear about why they are put on-call or asked to join an incident conference call bridge. We hear this frequently when we listen to recorded bridges for our clients. A technical expert will join and ask, “why am I here,” or “why do you need me?” Some discussion occurs to get the expert oriented to the fact that they have been called in to help resolve an IT incident. Valuable time is wasted that can never be recovered. To that end, it is critical to ensure that anyone who might be called upon to respond knows exactly why they are being summoned, what their role will be, and when they will be released from the incident by the IC.

This expectation setting starts at the top of the company’s organizational chart. It is mission critical that the executives set the tone for creating and supporting incident response by placing value on the effort, both within the IRT and across the company. Executives should strive to build a culture of incident response, ensuring predictability, repeatability, and optimization of the team. Again, it seems simple, but it’s vital that all responders know and understand what’s expected of them when they are called upon to respond, and that the incident consistency with which the team responds is ensured. For the incident response to be successful, this thought process and support must be baked into the company’s culture. The nature of the IT incident can and will vary, but the incident response approach should be clear and consistent.

Do all responders really understand that they are, in essence, functioning as the fire department for the company? We hear many fire department related references from site reliability engineers, SMEs, and executives. As an example, the use of the word triage is commonly used in IT. Its origin is as a common emergency medical term, meaning to sort and assign priority during an incident with many victims. The first person who responds to an IT issue is literally a first responder. As the issue may grow into an incident, the response must also scale, much like a fire escalating to a second, third, or fourth alarm. What’s strange is that many responders don’t see the public-safety-responder-to-IT-responder connection, nor feel the sense of responsibility that goes along with it. “We are so busy putting out fires,” said one engineer, “that I can’t find time to do my day job!” Said another way, while the rest of the company is building the business, the incident responders should be defending the business from harm.

Think of the point of clarity in this way: we all don’t need to think the same way during a response, but we must think in the same direction with the same viewpoint, unity of purpose, methodology, and focus.

Evaluated

Up to this point, the emphasis has been on putting the pieces in place to create an excellent incident response program. We will discuss the AAR process in Chapter 6, but for now understand that each incident response creates an opportunity to learn how to better respond to the next one. As we’ve heard in incident management over the years, “don’t let a good crisis go to waste!” Committing time and effort to objectively and specifically look at each part of the Incident Lifecycle, from the detection of an issue, dispatch of the incident responders and assembly of the Incident Response Team, through how the incident was ultimately resolved will most certainly offer lessons learned or areas that could be improved. The evaluation piece is where quality assurance (QA) and quality improvement (QI) efforts tie back to PROCESS.

- Quality Assurance (QA)

-

Taking an objective look at a behavior, decision, or circumstance and evaluating it against the established standard, ensuring the expected behavior is occurring.

- Quality Improvement (QI)

-

Finding opportunities, weaknesses, or missing pieces of the incident response mechanism and taking steps to correct/improve the deficiency.

QA and QI are investments that produce dividends over the long run. Tweaking the incident response process, the way in which the technical experts resolved the incident, and/or the leadership abilities of the Incident Commander may uncover weaknesses that are hampering your pursuit of excellent performance. There is much work underway in the area of “blameless post mortems” and we applaud those efforts. Today’s IT environments are large and complex. Not every use case can be anticipated or configuration tested for flawless operation with all of the other elements in the stack. Incidents also present the opportunity to find and correct defects. Let’s create a learning culture where incident information is used to improve the operations. It’s all about getting better—not finding fault or assigning blame!

When you uncover “landmines” of poor or inconsistent performance, you must identify them, acknowledge them, and do what it takes to improve the deficiency. Absent any thoughtful way of objectively evaluating the incident response process, poor performance may become the established norm and, culturally, it will be more difficult to change down the road.

Scalable

A powerful characteristic of IMS is that it works both for the smallest startup company with a few employees, to the largest companies with operations around the world. The scalable part of process is linked to predictability and repeatability in that a sound incident response process can quickly grow or shrink depending on the needs of the incident or growth of the organization. The latter refers to scalability at a program level rather than incident level, but as the organization grows, so grows the need for a larger and deeper pool of resources. We refer to this as bench strength. Bench strength is much like how sports teams look at scaling—having access to a wide variety of equally good talent to fill in the gaps for rotating, resting, or replacing players for the duration of the game. For example, as a company grows, the number of incidents will likely also grow and the company will need more qualified people to run production operations and incidents. Bench strength contributes to both the scalable and sustainable nature of PROCESS.

For IT, it’s important to acknowledge vacations, sick time, travel, shift coverage, etc. to maintain a high level of proficiency and availability of incident responders at all times. Since it’s unknown when the next big crippling incident might strike, the IT incident response process should be ever at the ready, just like a fire department. A team with good bench strength does not just have a handful of star players. It is comprised of a cadre of talent that can be interchanged, added, or expanded to meet whatever need is present. We have watched our customers’ environments get larger and more complex, by combining the scaling of capacity planning for future demand with technology refresh programs, all in the velocity of continuous code releases. Consequently, these environments fail harder and will require more focused incident management efforts as time goes on.

Ideally, the Incident Response Team establishes its identity and available resources by function so that it is not dependent on only a handful of people to respond on a regular basis. Many IT environments are already so complex that it takes a constellation of specific technical expertise to understand all of the various operational details. It’s quite common to require entire development teams, application teams, and database/storage/network experts to solve a single IT incident. With scale and complexity come even more specialization and the need to handle a larger volume and complexity of IT incidents, possibly happening concurrently. Therefore, being able to rapidly dispatch and obtain a greater number of varied and highly qualified technical experts, possibly from around the world, will help build a culture of effective response in the organization.

Sustainable

If the sales team needs to grow, loses talent, or needs to adjust strategy based on a change in business direction or philosophy, the company addresses those issues rapidly by hiring more people or reorganizing to avoid the risk of financial loss. When incident response passes the point of initial training and becomes a formal activity within an organization, the organization must view, care for, and value the Incident Response Team just like any other business unit.

Sustainability means that the incident response is indeed just as valuable as any other business unit, and deserves the same amount of financial commitment, executive leadership, and organizational development. Incident response in the IT field should not be viewed as a necessary evil, as we have seen in many organizations. Being on-duty to respond should be respected within the organization, intended to attract awesome and skilled talent. Incident response duty is painful sometimes—nobody likes to get up in the middle of the night on a regular basis—but this inconvenience is critical to the financial health and well-being of the company.

We say all this to underscore this point of sustainability. Few in the IT incident response business received any formal training on becoming an incident responder. Rather, individual technical skill or unique knowledge of an operating environment inadvertently leads them to the “tip of the spear” in incident response. Because a person may be a great engineer, they may be assigned to the Incident Response Team. Operations, specifically incident response as part of operations, is the place where technology and failure intersect, and the incident resolution process must be efficient to keep the business running. To that end, it is common to take great technical talent and bolt on incident response training, thus anointing the person as an incident responder, whether or not they are suited for the task. Many times, this approach works well and individuals make a smooth transition from technical expert to incident response technical expert, which are not necessarily the same thing. But many times, it simply does not work.

Again, establishing the culture of formalized incident response and looking after the team with support, leadership, and financial commitment will make attracting and keeping great talent a much easier task.

Summary

The goal of every business is to grow and create value. Every employee has a role and most spend their time building the business. Incident responders protect the business from the risks associated with service interruptions and outages. IT incident response is a specialized field in its own right and should be valued for its contributions to the long-term financial well-being of the company. The first step to building a successful incident management team is to conduct an honest assessment of the status quo. The following list of key points and concepts is a distillation of PROCESS in an easy-to-digest format:

-

PROCESS is an acronym you can use as a programmatic evaluation tool. Using each point to guide a discussion about the various aspects of your incident response process can provide insights into areas you can improve.

-

There should be no doubt about who is available to respond and who is available in the incident response talent pool.

-

You should be able to respond the same way, every minute of every business hour.

-

Team members should be trained, equipped, and ready to do the job the company is asking them to do.

-

Everyone on the Incident Response Team should know exactly what is expected of them, what their role is, what latitude they have to make decisions on an incident, and know that they have support from executive leadership to resolve incidents to protect the business.

-

Good incident response process can rapidly scale up and scale down to match the needs of the incident.

-

Successful incident response programs are built to be sustainable in terms of recruiting and retaining the best talent.

-

An organization should build and maintain a culture of incident response and view it as important as any other business unit.

-

There is a difference between event, alert, incident, dispatch, and notification. If your company hasn’t made that crystal clear to all responders and throughout the entire company, we suggest you do. We run into many companies that haven’t done that and it creates confusion during the process of assembling the right team at the right time to do the right things.

Get Incident Management for Operations now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.