Chapter 7. What Critique Looks Like

The Two Sides of Critique and the Importance of Intent

There are two sides, or roles, in any critique:

- Recipient

The individual(s) receiving the critique (that is, the designer or presenter of whatever is being analyzed) who will take the perspectives and information raised during the critique, process it, and act upon it in some way.

- Giver

The individual(s) giving the critiqueâthe criticsâwho are being asked to think critically about the design and provide their thoughts and perspectives.

Within both of these roles there is the discrete aspect of intention: why are we asking for/receiving/giving feedback? Intent initiates conversation and is often what separates successful critiques and feedback discussions from problematic ones.

For the best discussions, the intent of each participantâregardless of whether they are receiving or giving critiqueâneeds to be appropriate. If we arenât careful, critique with the wrong or inappropriate intent on either side can lead to problems not only in our designs, but also in our ability to work with our teammates.

Receiving critique with the appropriate intent is about wanting to understand whether the elements of the design will work toward the established objectives for the product.

Giving critique with the appropriate intent is about wanting to help the designer understand the effect that elements of the design will have on the productâs ability to achieve its objectives.

Both acts are done with the intention of using the information and perspectives raised during the critique to modify and strengthen the design. This is an important aspect of the discussion. Many of us have experienced meetings during which weâve been asked to give our thoughts on something like a design, or a process, or maybe even a project (for example, a postmortem or retrospective). Over time, if these discussions repeatedly fail to produce action and changes, our desire to participate and provide our perspectives wanes.

Part of what makes for strong critiques is the desire to participate and to help. To be certain, everything said in a critique is not going to produce a discrete modification to the design. But overall, participants should feel that the discussion, to which they actively contributed, will play a role in improving the designânot just changing it, but strengthening its ability to produce the desired objectives.

Prior to beginning a critique, whether youâre the giver or receiver, itâs best to ensure that youâre going in with the right intent.

Giving Critique

Giving critique with the right intent is about wanting to contribute to the improvement of the design by helping the designer understand the relative success design elements will have in working toward the stated objectives. When we approach our feedback discussions with this mindset, we think critically about what weâre saying and why weâre saying it. By considering both the what and the why, we keep conversations productive.

To better understand what giving a good critique looks like, letâs first analyze some characteristics of bad critique.

The Characteristics of Bad Critique

In most cases, what causes a critique to be characterized as âbadâ is usually a set of behaviors or characteristics exhibited by those involved. The following subsections present a few that we have seen.

Selfish

Bad critique can sometimes be the result of selfish intention. Thatâs not to say that it is always malicious, but it might be focused on or driven by the criticâs personal goals and come at the expense of the team or other individuals, specifically the designer of whatever is being discussed.

In extreme cases, selfish critique comes from the motivation of the giver to not only be heard and attract attention, but also to be recognized as smarter or superior.

The most recognizable examples of this can be seen on social networks such as Twitter or Facebook whenever there is a change to a popular app, device, or other trend-worthy product. A new feature is added or something is changed, and people immediately begin slamming decisions, labeling them ridiculous and stupid, and stating how things âshould have been designed.â

But in most of these situations, the commenters have only a cursory understanding of what the designer or team was working toward and the constraints they were working within. How is this helpful?

When we do this (and Aaron and I are guilty of it, too), are we really trying to help someone improve his design? Or are we more interested in showing others in our community or organization how smart we are on a certain topic?

Selfish critique and feedback happens on project teams, as well. Maybe youâve encountered it at work, are thinking of a colleague whoâs done it to you, or maybe youâve done it yourself.

Sometimes, this kind of feedback comes from having our own ideas of what we think the design should be, but not having had a chance to share them with the team. So, we set about to use feedback as an opportunity to propose our own alternative ideas for how something could be done. Although Aaron and I are firm believers that a great idea can come from anywhere, and team members in any role should be given an opportunity to share their ideas, doing so during a critique is detrimental.

Critique is not the place for exploring new ideas. Its purpose is to analyze the design as it has been created so far. Shifting a group from an analytical mindset to an explorative one is best done with deliberate facilitation.

Itâs important here to recognize that not all selfish critique is malicious. Some individuals might simply be unaware of their tone, or they have difficulty forming their feedback in a way that is useful. When presented with selfish feedback, we have an opportunity, and often a responsibility, to work to understand what someone is trying to tell us and determine if it is useful in helping to improve our design.

Untimely

Despite what you might think and what some people might even say, people arenât always looking to hear feedback on their work. Unless someone has specifically told you that they would like your feedback, itâs unwise to think your conversation is a great opportunity to share your analysis with her. If someone is telling people about her creation, it might just be to get the word out or simply that sheâs excited about the project.

For the receiver to really listen, process, and make use of critique, she needs to be in the proper mindset. Whether at a team memberâs desk, in a meeting, or on social channels, when critique is uninvited, it can lead to defensiveness, communication breakdowns, and often paints the person giving the critique as a âknow it all.â

Incomplete

For critique to be useful, the designer(s) need to understand not just the potential outcome or reaction to an element of their design, but the âwhyâ behind it. We often see feedback in the form of things like, âI think the button is better than the linkâ or âNobody is going to click that.â Or, even worse, âThis is terrible...â

This type of feedback typically comes from the reactive form of feedback discussed in Chapter 6. It lacks the critical thinking that makes it possible for those working on the design to understand what they might need to change in their next iteration. For these critiques to become valuable, they need to be followed by an explanation as to âwhyâ the giver is having that reaction or foresees a certain outcome. For example, âNobody is going to click on that because the current page design leads the eye down the left side of the screen away from the call-to-action.â

Good critique is actionable. When the âwhyâ behind the feedback is included, the designer can fully understand the comment and take action. That is to say that the designer has enough of an understanding of what is and isnât working and why it isnât working that she can explore alternatives or make other adjustments.

Be aware though that this is different from prescription or direction. Critique should not tell the designer how to act on something or specifically what changes she should make (the directive form of feedback). Good critique avoids problem solving because it can detract and distract from the analytical focus of the discussion.

Preferential

Another common characteristic of bad critique is feedback that is justified by the giver from purely preferential thinking. Weâve all heard horror stories about this kind of feedback. Designs are torn apart not because a particular aspect isnât working toward its objective, but rather because it doesnât match exactly what the critique giver âlikes.â For example, a website design is discarded because the color scheme reminds a stakeholder of a Christmas sweater his ex-wife gave him.

It might seem ridiculous, but this kind of feedback is common, though maybe not always so extreme. It usually feels like itâs coming out of nowhere and has no relevance to the work weâre doing, but sometimes, it really just boils down to a personal preference.

This kind of feedback is not only unhelpfulâit does nothing to analyze a design with regard to objectivesâbut it can also be distracting and counterproductive. This is especially the case when it comes from team members or stakeholders who are in a position of approval. In these situations, the team begins, consciously or subconsciously, to prioritize that individualâs tastes alongside or above project and user goals, even if they conflict.

Best Practices for Giving Critique

Whereas critique with the wrong intent (done knowingly or not) is harmful and can damage teams, processes, and most important the product, useful, productive critique has the ability to strengthen relationships and collaboration, improve productivity, and lead to better designs. To give the best critique possible, think about the following best practices when giving feedback.

Lead with questions

Get more information to base your feedback on and show an interest in their thinking.

Chances are, before being asked for your feedback, the presenter will give a brief explanation of what he has put together so far and how it would work. This gives you some context and understanding of the objectives he has and the elements of the design he has put in place to achieve them. But he likely hasnât explained everything. Actually, as weâll talk about later on, hopefully he hasnât explained everything.

This is your chance to open up the dialogue. By asking questions you give yourself more information on which to base your analysis and give stronger, actionable feedback. If done in a noninterrogative way, it shows the designer that youâre genuinely interested in not only his work, but the thinking behind it, which can make discussing it and listening to feedback easier for him.

Examples of questions you might ask:

Can you tell me more about what your objectives were for [specific aspect or element of the design]?

What other options did you consider for [aspect/element]?

Why did you choose this approach for [aspect/element]?

Were there any influencers or constraints that affected your choices?

Remember though, the dual purpose of asking these questions of the designer:

To get more information

To make the designer more comfortable talking about his thought process and decisions

How you ask these questions can have a huge impact. Asking every question beginning with âWhy...â can feel abrasive or like an attack. Use lighter, more inviting phrasing such as, âTell me more about...â

Use a filter

Hold on to your initial reactions, investigate them, and discuss them in the proper context, as appropriate.

Youâre going to have reactions. As the work is being presented to you, there will be things that make you think âHuh?â or âThatâs cool,â or âI donât get it,â or maybe something worse. Hold on to those reactions and remember that they donât typically make for useful feedback. Ask yourself why youâre reacting in that way. Ask the presenters additional questions if necessary to help you understand your reaction.

After you understand your reaction and what caused it, think about when it makes the most sense to discuss that reaction and to what length. Does it relate to the objectives of the product, the audience for it, or any particular best practices that should be followed? Or, is it more about your personal preference or wishes for how youâd like to have seen it designed?

If your feedback is related to the productâs objectives or best practices and not about your personal reaction or preferences, it likely has a place in the conversation. Sometimes, though, you might find yourself with feedback that, although not a best practice or preference, is also not specific to a best practice or a stated objective. Maybe itâs something new that you think should be considered. What should you do in those situations?

In these cases, it might still be useful to bring your feedback into the conversation. These kinds of thoughts can be useful in determining additional objectives or constraints for the project that need to be exposed. It might be something you can discuss quickly and then continue on with the critique, or it might prove to be something sizeable that needs a separate, dedicated discussion so that the critique isnât derailed.

Donât assume

Find out the thinking or constraints behind choices.

âTo assume makes an ass out of you and me.â Most of us have probably heard that line a few times in our lives. Itâs one of the favorites of Adamâs father and it has stuck with him.

Making assumptions can be one of the worst things to do during a critique. When we make assumptions we begin to form our thoughts, questions, and statements around them, without ever knowing whether theyâre accurate. Before you know it, the participants of the discussion leave to work on their action items based on very different ideas and produce work that doesnât align with that of the other participants.

When you make assumptions in a critique about what an objective or constraint might be, or maybe that there were no constraints and the designer could have done anything, you begin to offer feedback that could be less useful because it isnât based on the real situation.

Avoiding assumptions is simple: ask about them.

Yup. Ask yet more questions. Put your assumption out there and ask if itâs accurate. If it is, continue on with your insights. If it isnât, you might need to adjust your thinking a little.

For example, if your feedback is based on the assumption that the designer had no constraints and could have done anything, ask him if he faced any constraints that influenced his choices. Or perhaps ask him if he had wanted to take a different approach but couldnât due to a constraint.

Donât invite yourself

Get in touch and ask to talk about the design.

In the previous section, we noted untimely feedback as one of the types of unhelpful critique. If the recipient of the critique isnât of a mindset or isnât ready to listen to the feedback and use it, chances are she will ignore it or the critique could potentially cause a rift in your working relationship.

If you have thoughts about someoneâs design and she hasnât explicitly asked for your feedback or critique, get in touch with her first and let her know. Politely suggest that when sheâs at a point when your thoughts might be helpful, youâd be happy to share them. Give her the opportunity to prepare to listen.

Talk about strengths

Critique isnât just about whatâs not working.

We sometimes have a tendency to focus on negatives, the things that cause us problems, get in our way, and that weâd like to see changed. We often take the positive for granted. In our project meetings and design discussions itâs often no different. We spend the vast majority of time talking about what isnât working. But that can be harmful. Remember that critique is about honest analysis. It should be balanced, focusing on the design and its objectives, regardless of their success. Itâs just as important to talk about what is working and why as it is to talk about what isnât working.

Often when talking about the role of âpositive feedbackâ in critique, we see discussions center on the importance of discussing strengths as a mechanism for making critical feedback easier for the receiver to take. There is a common structure often discussed called the âOREOâ or âsandwichâ method in which you begin by offering a positive piece of feedback, followed by a negative one, followed by another positive one. Itâs a fairly common technique.

But there are other reasons for making sure that critiques include discussion on what aspects of the design are working toward objectives and why and how.

Part of the design process involves the deconstruction and abstraction of ideas and then recombining them in different ways or with ideas from somewhere else. Itâs a common way in which we take a familiar concept for which there is room for improvement or added value and then innovate from there. When we talk about aspects of a product or design that are working, there is the potential for the designer to examine those areas and abstract concepts or elements from them that could be used to strengthen other areas of the design that might not be working as well.

Additionally, with the understanding that the designer(s) will iterate upon his design after a critique, how bad would it be if at the next critique you noticed that an aspect of the design that seemed great previously had now been changed and wasnât quite as effective. And this happened because it hadnât been talked about, so the team didnât see a reason not to change it.

Think about perspective

From whose âangleâ are you analyzing the design?

In the previous section, we talked about preferential critique, or feedback thatâs based on personal preferences rather than being tied to objectives for what weâre designing. When weâre analyzing a product, it can be easy to forget that we most likely arenât representative of the productâs target audience. Even if we are a potential user, we know far more about it than the average user.

As you analyze a design, itâs important for you to try to balance your expertise against the userâs perspective. It can be difficult to achieve, but by simply asking yourself, âHow am I looking at this?â when you examine an aspect of the design and comparing your perspective to what you think the userâs might be, youâre off to a good start. From there you might find that one is clearly more appropriate than the other (your visceral hatred of the shade of green being used probably doesnât matter), or perhaps it might be best to bring both up in the discussion. For example:

From the userâs perspective, I think all of the steps in this flow make sense and are understandable and useable. But from an interaction design perspective I think there might be some redundancy and opportunities to simplify...

A Simple Framework for Critique

Itâs helpful to have a sense of what the structure of a good critique sounds or looks like. As Chapter 6 instructs, critique contains three important details:

It identifies a specific aspect of the idea or a decision in the design being analyzed.

It relates that aspect or decision to an objective or best practice.

It describes how and why the aspect or decision works to support or not support the objective or best practice.

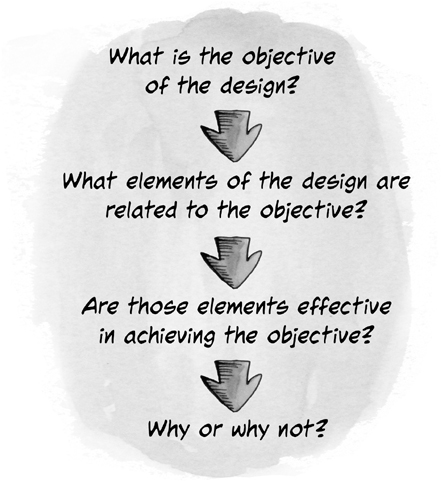

To ensure that we uncover and include all of these details there is a simple framework of four questions that we can ask ourselves, or the other individuals participating in the critique, as shown in Figure 7-1.

Figure 7-1. The four questions that comprise the basic critique framework

These four questions flow together to generate feedback in the form of critique. By asking these questions, we collect the necessary information with which we can think critically about the design weâre examining. Letâs take a look at these questions individually.

- What is the objective of the design?

We want to understand what weâre analyzing the design against so that we can focus our attention on things that are pertinent to the conversation and the improvement and success of the design. Try to identify the objectives that the designer was aiming to accomplish through the choices she made. What are the objectives of the product or design that have been agreed upon by the team?

- What elements of the design are related to the objective?

Next we identify the aspects and elements of the design that we believe work toward or against the objective. Whether the aspect or element is the result of a conscious choice by the designer doesnât matter. We are analyzing the effectiveness of the whole design as itâs presented.

- Are those elements effective in achieving the objective?

Now that we are thinking about specific objectives and the aspects of the design related to them, itâs time to ask whether we think those choices will work to achieve the objective. This is the crux of critical thinking.

- Why or why not?

Finally, we need to think about the result that we think the choice will actually produce. How close is it to the actual objective? Is it completely different? Does it work counter to the objective? Maybe it wonât work to achieve the objective on its own, but in conjunction with other elements of the design it contributes to the objective.

Note that the first two questions can be reversed in order depending on how the design is being presented. These questions form the foundation for the critical thinking that comprises good critique. As such, these questions can be asked and answered internally by individuals giving feedback, or they can be exposed and asked directly of the designer. As mentioned in the earlier section on best practices for giving critique, itâs great to lead with questions. And questions that ask about what choices were made and what objectives those choices were intended to achieve are a great way to start the conversation.

Other questions to think about

The four framework questions help us formulate feedback that a designer can use to better understand the effectiveness of his choices when viewed against his objectives. But, what about other aspects of the design? What about other questions that come up? For example:

What new problems, complications, or successes might arise from the choices being proposed?

What other objectives should the designer have been considering, but didnât?

Raising these kinds of questions can be important. Ignoring them might mean missing something that becomes problematic later in the projectâs timeline, or it might give rise to a new objective for the team to discuss and agree to (or discuss and agree isnât an objective).

With additional questions like these, however, itâs important to keep in mind scopeâboth the scope of the product and the scope of the feedback discussion. These questions can lead to spending too much time discussing things that are outside the scope of the project or product itself, like perhaps a known issue that the product isnât intended to solve. Or, questions like these can take the focus off of the aspects of this design for which the presenter is looking for feedback, and instead use up valuable time on elements of the design that havenât been fully thought out yet and are likely to change anyway.

The group, both the recipient and the givers, need to be conscious of this potential for scope-creep and be prepared to end or defer a discussion when it begins to move out of scope.

About objectives

As weâve mentioned and will continue to reference throughout the book, critique is about analyzing something against its objectives. But what exactly are these objectives?

Additionally though, when we describe objectives, we should be considering best practicesâheuristics that have been established over time to help us understand how best to approach or solve for a given situation. Ignoring these in a discussion would be detrimental. As you analyze someoneâs work, itâs likely that, if you are well versed in a certain set of heuristics, youâll identify areas of the design that are in or out of alignment with those best practices. These observations should be included in the discussion. An objective of anything we design should be to align with best practices where applicable.

Receiving Critique

Listening to people comment on something youâve created can be scary. It can be difficult enough to present something to a group of people, never mind the possibility that they then might begin to pick it apart.

While I was in film school, at the end of each year we were required to present our final film to an audience of classmates, instructors, family, and friends. At the end of my first year, I presented my work, a short film that debated who was the better superhero, Batman or Superman (the answer is Batman, of course). Following the credits, I walked to the front of the room, talked for a few minutes about it and waited for the comments.

I didnât have to wait long.

One of the professors began to tear into it, commenting on how pointless it was, how little depth it had, how the actors didnât move enough yet were working in a medium called âmovies.â

Those 12 minutes still haunt me. And for a very long time after that, I was terrified of showing my workâany work. On multiple occasions over the years, that fear became so significant that I threw out everything I created. Even when I moved into the business world, the prospect of standing there and listening to feedback terrified me. And, unfortunately, Iâve had numerous encounters with coworkers that have reaffirmed that fear.

ADAM

Many of you might have had similar experiences, or have heard enough horror stories that you feel like itâs happened to you, too. All of this fear and trepidation can lead us to change our behaviors and expectations when presenting our work and asking for feedback.

Just like giving critique, receiving it in a way that is useful and productive requires the recipient(s) to have the right intentions. When receiving critique you should be in a mindset to step back from your creative thinking to examine the choices youâve made to better understand how to proceed and take your design further. And you should value the expertise and perspectives of your teammates in doing so.

Often, though, we see individuals and teams go through the process for the wrong reasons, leading to issues down the road as the project progresses, both for the product and the teamâs relationships.

Critique Anti-Patterns

When engaging in critique, there are patterns (or behaviors) that go against critique best practices and can hinder the critique process. The sections that follow describe these patterns.

Asking for feedback without listening

Sometimes, we ask for feedback because we feel like itâs the right thing to do, or because we feel like we have to. Although stepping back and forth between creative thinking and analytical thinking is a key component of a successful design process, it isnât the case that weâre always in a position mentally or tactically to listen, consider, and utilize feedback to improve our designs.

If we ask for feedback or critique, we need to be ready to listen to whatever we receive in response. Asking for critique at a time when we donât really want it or canât do something with it leads to unproductive discussions. By not listening to our teammates, we miss valuable insights that can help improve our designs. The people critiquing our work are likely to pick up on your disinterest and, as a result, will feel uninterested in sharing their thoughts. Over time, theyâll be less inclined to participate in these kinds of conversations at all.

Remember the importance of being able to switch between creative and analytical thought. Getting used to making this switch between creative and analytical thinking may not always feel comfortable. But if we learn how to use it effectively, by making critiques a scheduled part of our process, it can go a long way to strengthening us and our teamâs skills as designers.

Asking for feedback for praise or validation

Creating something can feel awesome. Whether weâre designing alone or as part of a team, itâs not unusual to want to be recognized for our creations. But it should not become our motivation for asking for feedback.

And yet we do it often. We share our work with statements such as âHey! Check out this thing I just made! Iâd love your thoughts on it,â when really the only thoughts we want to hear are âWay to go! Looks awesome!â and âCongratulations!â

So we wait for the cheers. Some come, and it feels great. But then we get some feedback about things that arenât so great or things we could have done better, and it hurts. No matter how valid the points might be, we might not be in the proper mindset to hear them. Some people will become defensive. Others might argue and try to discredit the feedback. Some ignore the comments. But either way, we havenât done a very good job at receiving critique, even though you asked for it.

Not asking for feedback at all

Because youâre reading this book, and youâve made it this far in, hopefully you understand the value in critique and how it can help you to improve your designs and products. If thatâs true, then you should also see how important it is to seek out critique.

If we donât take the initiative to ask for critique or feedback in a way that helps us understand and improve upon our ideas then weâll miss a huge opportunity. We canât just assume that others will come to us with feedback. And we canât assume that just because no one comes to us that weâve designed the perfect solution. By bringing others in to help us analyze our ideas we can take advantage of their experience and expertise to inform our design decisions in ways we arenât able to do on our own.

Best Practices for Receiving Critique

Receiving critique in a way that is productive goes beyond just asking for it and then sitting back to let others give you their thoughts. When receiving critique, keep in mind the best practices that follow.

Remember the purpose

Critique is about understanding and improvement, not judgment.

There is no such thing as a perfect solution. There is always room for improvement. A goal of a critique is to help identify where those opportunities are. The conversations we have during critique act as road-signs along the evolution of our ideas and designs, helping us to understand which paths might take us closer to our end goals. Critique isnât about pass or fail, approval or rejection. It is a reflection used to inform a next step.

Listen and think before responding

Many of us have a bad habit of not really listening when someone is speaking to us. We hear the first few words they say, and then instead of listening to the remainder of what theyâre saying, we begin to formulate a response and wait for the first opportunity to start talking.

What this means is that while the person we should be paying attention to is explaining a thought, instead of listening to and processing that explanation weâve essentially ignored it. Itâs not that weâve done so maliciously; this is a common occurrence and most of us do it. Obviously though, this is counterproductive to what weâre trying to do in a critique.

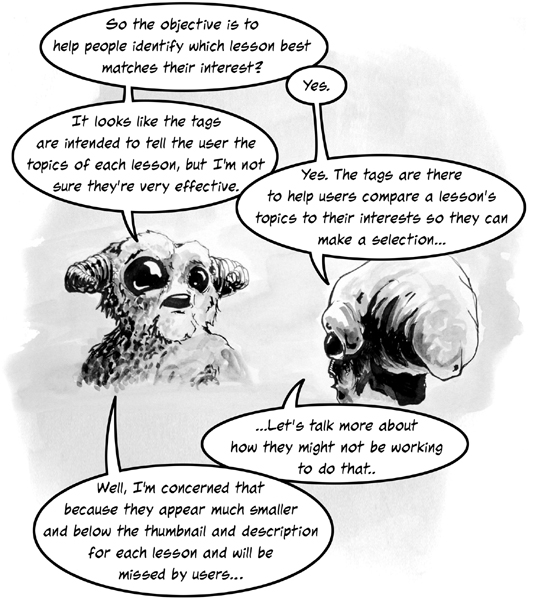

When receiving critique itâs important that we work toward preventing any natural tendencies to form rebuttals and instead focus on listening to peopleâs entire thoughts. This doesnât mean that as the recipient we must sit silently throughout the critique. Figure 7-2 shows thatâafter listening to a piece of feedbackâthe responses we give should be intended to ensure that we understand what the critic is trying to tell us. We can ask what the critic means. We can answer his questions. We can provide more details about how we came to the decisions in our designs if itâs necessary to help the critic with his analysis.

Return to the foundation

As people share their thoughts with you, you might encounter feedback that seems out of place. It might seem as though the feedback has little to do with what youâre trying to design or the objectives you have. The person youâre hearing from might just be having difficulty connecting her thoughts, or it may be that she has begun to offer feedback that is based more on her own preferences or goals.

Figure 7-2. Demonstration of dialogue that helps ensure stronger feedback by allowing the recipient to seek clarification and ask questions in order to make sure they understand what is being said

To help you determine this, you can use previously agreed-upon objectives. A productâs objectives describe the reasons for its creation, who it is for, and what it will do. If you canât determine for yourself how the feedback relates to the product or projectâs objectives, try to work with the person giving the critique on relating it back by asking her follow-up questions related to the objectives.

If, over time, youâre able to determine a connection, youâll better understand the feedback and can use it moving forward. If not, you might have discovered that members of the team share different views on what the objectives of the product and its design are.

Having a mutually understood foundation or set of objectives is important not just to critique but also to the success of the product and the team. If you discover during a critique that different perspectives about objectives exist within the team, the best course of action is to point it out explicitly. You can then, depending on its severity and the people present, determine if the conversation should change focus to addressing and resolving the difference right then, or if it should be tabled for a separate conversation in the near future.

Participate

One of the best things a designer can do during a critique is to become a critic themselves. Being able to shift our mindset from thinking creatively to being analytical about what weâre designing is a key design skill. Participating in a critique of our own work as a critic has multiple benefits.

First, the more we exercise intentionally switching our mindset like this the easier it becomes to control this mindset âtoggle.â Switching from creative thinking to analytical will be easier, faster, and something we can do whenever we feel like itâs helpful, whether we do it by ourselves alone at our desks, or we grab the person sitting next to us for their thoughts, or we schedule a meeting to collect critique from a larger group.

Second, one of the common challenges people have with giving critique is a fear of hurting the designerâs feelings. By participating in the analysis and openly talking about the aspects of our design that could be improved upon, we can make others feel more comfortable participating in these discussions.

Third, by modeling the behavior and the form of critique, we demonstrate to the other participants how to give feedback in a way that is helpful to us, making it easier to collect useful critique and facilitate the conversation.

Critique, Conversation, and Questions

Good critiquesâthat is, critiques that are productive for the entire teamâare the result of dialogue. The giver and receiver request and exchange information back and forth, and from those exchanges come useful, actionable insights. In a productive critique, there are often a lot of questions asked by both parties.

In fact, great critiques are often more about questions asked than statements made. Questions being asked means that assumptions can be validated, eliminated, or further examined collaboratively. This means that the feedback being collected is based upon a mutually understood foundation rather than each individualâs different interpretations. Itâs also useful for the recipient to pay attention to the questions being asked because they can be signs as to what elements of the design might be unclear or confusing to others.

This should also tell you something about how best to ask for feedback and which communication platforms make the most sense. Itâs common for designers or teams to send their designs to other members of the team via email and ask for feedback. Itâs also common for these kinds of exchanges to become problematic.

Email isnât a great conduit for anything resembling real-time conversations. It isnât designed to work that way, but being able to quickly ask questions and get back responses that may assist in advancing your thinking, spur additional questions, or provide insights is crucial. When dealing with multiple people giving feedback, these deficiencies become even more pronounced, because now you need to manage threads, keep track of who gets what information via replies and reply-alls, and so on. Weâve all likely experienced situations in which feedback was originally solicited by email, and after one or two replies, a conference call or in-person meeting was set up because it just seemed easier than trying to make sense of the lists of questions and comments coming back.

Online feedback tools like inVision and others do their best to try to work around this by making it possible for people to comment on specific aspects of a design and keeping those threads together. This works better, but the non-real-time nature can still prove challenging, because in order to give comments, individuals must do so based on assumptions that they havenât yet been able to validate or eliminate.

That isnât to say that critique isnât possible through these mechanisms. It very much is, but, if weâre going to use tools like this, perhaps because weâre in a situation for which we have no other choice, we need to ensure that weâre doing our best to make them as conversational and focused as possible.

When requesting feedback through a mechanism like this, be specific about what you want feedback on in your request. Specify what the objectives for your product or design were. Allow for as many questions back and forth as you can. When making assumptions in order to offer an insight, be sure to state that assumption so that the recipient can see it and verify that itâs true or let you know that it isnât.

It takes more work and can often take a bit longer, but it can be done. We do recommend that, when you can, itâs best to use a platform in which everyone can communicate in real time and look at the design together. With some good facilitation youâll find that in sessions like this, whether theyâre in person or through a conferencing tool like WebEx or Google Hangouts, youâll do much better at collecting useful feedback, keeping the team synchronized, and building a sense of collaboration.

Wrapping Up

Good critique begins with both the giver and recipient having the right intentions: wanting to understand whether the elements of the design will work towards the objectives of the product.

Following are the characteristics that make feedback unhelpful:

Itâs driven from personal goals.

Itâs untimely.

Itâs incomplete.

Itâs based on preference.

To help ensure your feedback is useful and works toward improving the product, you should do the following:

Lead with questions.

Get more information to base your feedback on and show an interest in their thinking.

Use a filter.

Hold on to your initial reactions, investigate them, and discuss them in the proper context, as appropriate.

Donât assume.

Determine the thinking or constraints behind choices.

Donât invite yourself.

Get in touch and ask to talk about the design.

Talk about strengths.

Critique isnât just about whatâs not working.

Think about perspective.

From whose âangleâ are you analyzing the design?

Similarly, when asking for feedback, be sure that you arenât do the following:

Asking with no intention of listening

Asking when youâre really just looking for validation or praise

When asking for critique, keep the following in mind:

Remember the purpose.

Critique is about understanding and improvement, not judgment.

Listen and think before responding.

Do you understand what the critics are saying and why?

Return to the foundation.

Use agreed-upon objectives as a tool to make sure feedback stays focused on objectives.

Participate.

Critique the work alongside everyone else.

If we understand the best practices for giving and receiving critique, we also notice a few things about how we collect feedback through various platforms. The more weâre able to facilitate real-time question-and-answer sessions across the group, the better the exchange is likely to be. This is why in-person meetings and videoconferencing tend to be best. However, we can still use feedback tools and email; they just take more planning and careful facilitation.

Get Designing for the Internet of Things now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.