Chapter 1. What Exactly Is “Mixed Reality”?

I don’t like dreams or reality. I like when dreams become reality because that is my life

Jean Paul Gaultier

The History of the Future of Computing

It’s 2016. Soon, humans will be able to live in a world in which dreams can become part of everyday reality, all thanks to the reemergence and slow popularization of a class of technology that purports to challenge the way that we understand what is real and what is not. There are three distinct variants of this type of technological marvel: virtual reality, augmented reality, and mixed reality. So it would be helpful to try to lay out the key differences.

Virtual Reality

The way to think of virtual reality (VR) (Figure 1-1) is as a medium that is 100% simulated and immersive. It’s a technology that emerged back in the 1950s with the “Sword of Damocles,” and is now back in the popular pschye after some false starts in the early 1990s. This reemergence is predominantly down to a single company—Oculus—and its Rift Developer Kit 1 (DK1) headset that successfully kick started (literally) the entire modern VR movement (Figure 1-2). Now, in 2016, there are many companies investing in the space, such as HTC, Samsung, LG, Sony, and many more, and with this, a raft of dedicated startups and investment that has only served to fuel interest. VR will likely become the optimal way that one experiences games and entertainment over the next decade or so.

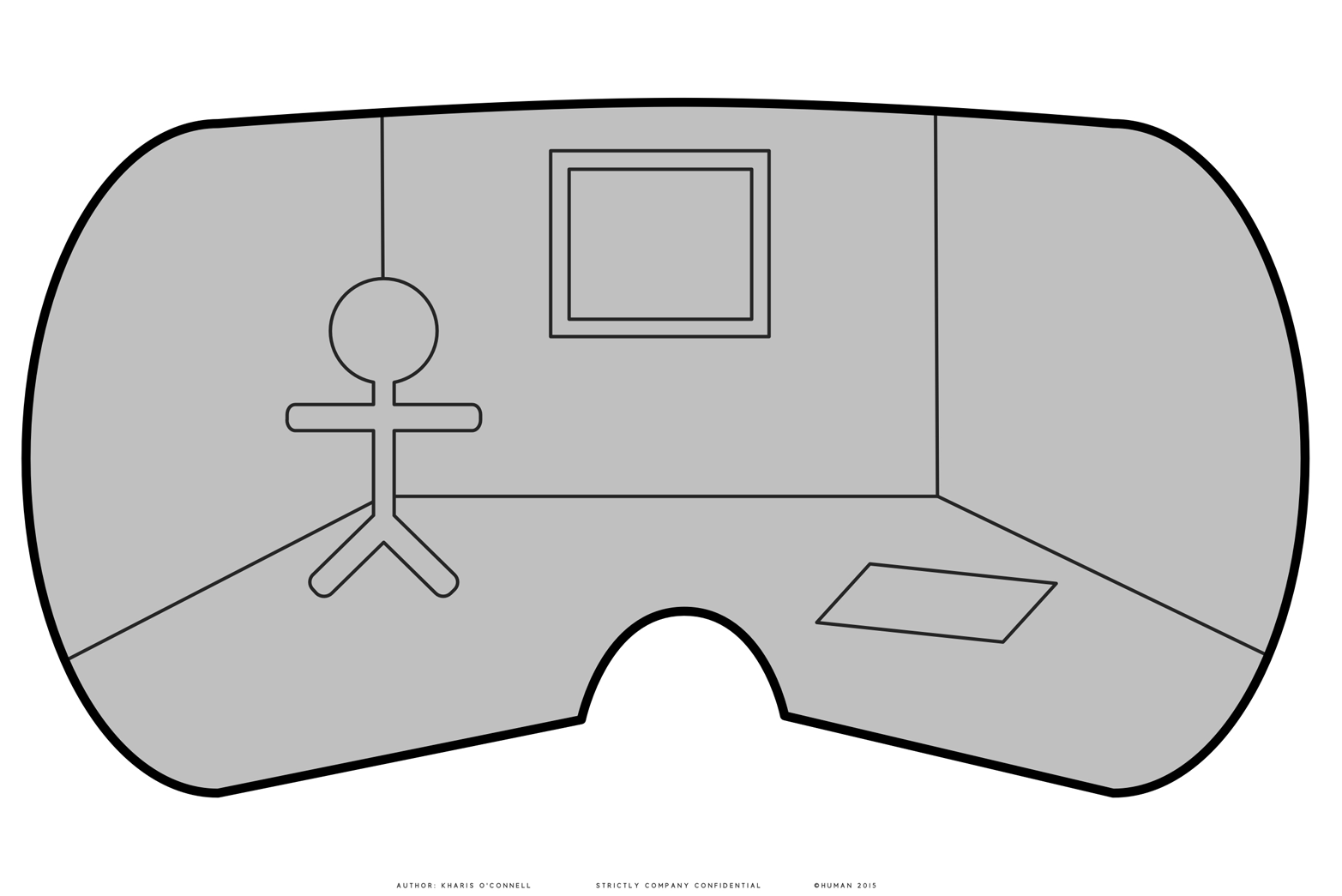

Figure 1-1. Virtual reality—everything you see is simulated, and the real-world environment in which you experience VR is not taken into account

Figure 1-2. The Oculus Rift DK1 headset—arguably responsible for the rebirth of VR

Augmented Reality

Augmented reality (AR) (Figure 1-3) became popularized as a term a few years back when a few of the first wave of smartphone apps began to appear that allowed users to hold their smartphones in front of them, and then, using the rear-facing camera, “look through” the screen and see information overlaid across whatever the camera was pointing at. But after many apps implemented poorly-concieved ways to integrate AR into their app experience, the technology quickly declined in use, as the novelty wore off. It reemerged into the public consciousness as a pair of $1,500 glasses—Google Glass, to be precise (Figure 1-4). This new heads-up-display approach was heralded by Google as the very way we could, and should, access information about the world around us. The attempt to free us from the tyranny of our phones and put that information on your face, although incredibly forward-thinking, unfortunately backfired for Google. Society was simply not ready for the rise of the Glasshole, and so, after many months of the mocking and joking reaching critical mass, Google pulled the product from the market. There are still many manufacturers making AR headsets (Vuzix, Recon, and Epson, among others) that are still a popular choice of technology for many industrial use cases, such as logistics.

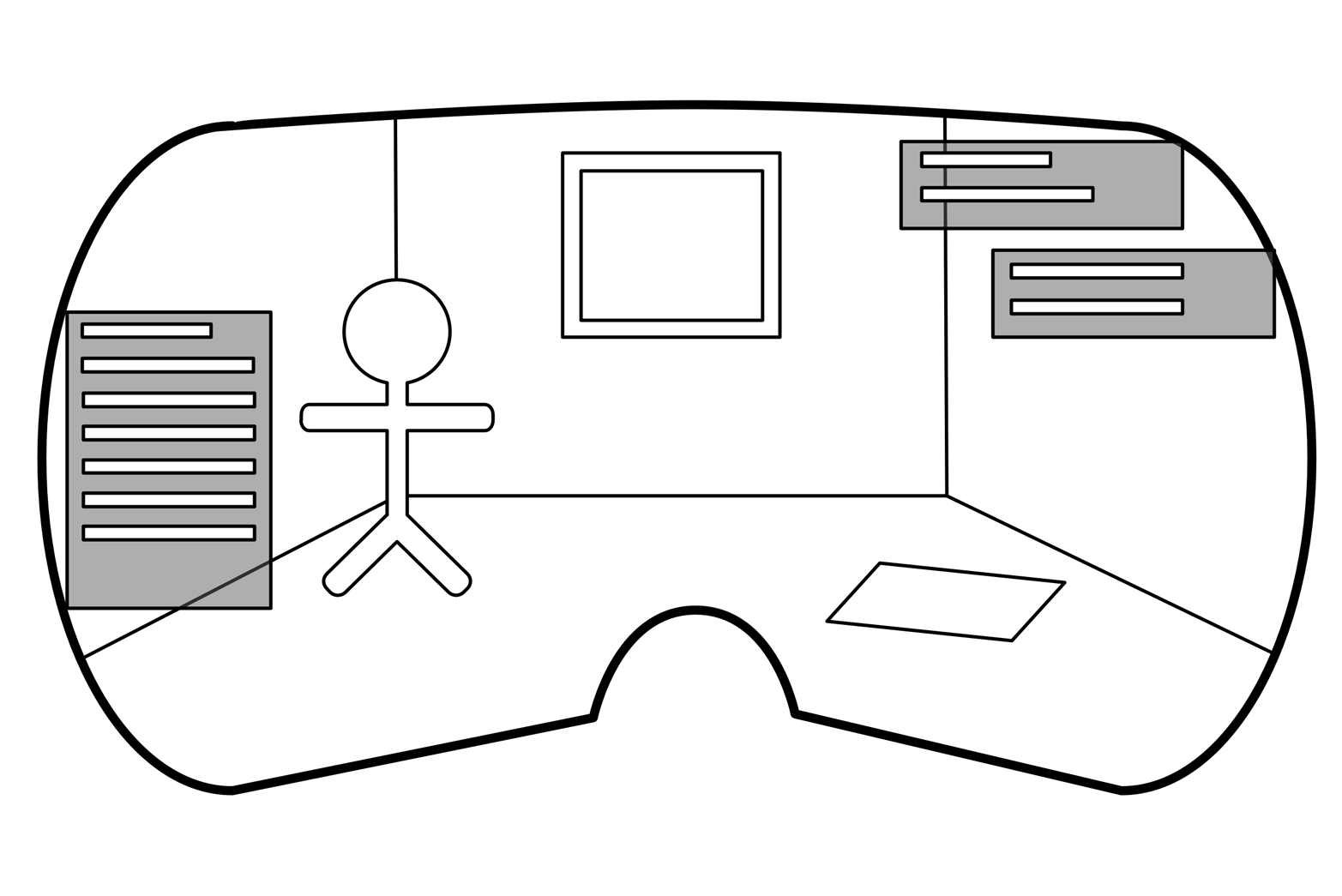

Figure 1-3. Augmented reality—everything you see is real, with an extra data layer superimposed into your field of view, and the environment in which you experience AR is often not taken into account

Figure 1-4. The (now infamous) Google Glass augmented reality headset (“Google Glass” by Tim Reckmann. Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/115225894@N07/13987153880. This photograph is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic License.)

Mixed Reality

Mixed reality (MR) (Figure 1-5)—what this report really focuses on—is arguably the newest kid on the block. In fact, it’s so new that there is very little real-world experience with this technology due to there being such a limited amount of these headsets in the wild. Yes, there are small numbers of headsets available for developers, but nothing is really out there for the common consumers to experience. In a nutshell, MR allows the viewer to see virtual objects that appear real, accurately mapped into the real world. This particular subset of the “reality” technologies has the potential to truly blur the boundaries between what we are, what everything else is, and what we need to know about it all. Much like the way Oculus brought VR back into the limelight a few years ago, the poster child to date for MR is a company that seemed to appear from nowhere back in 2014—Magic Leap. Until now, Magic Leap has never shown its hardware or software to anyone outside of a very select few. It has not officially announced yet—to anyone, including developers—when the technology will be available. But occasional videos of the Magic Leap experience enthrall all those who have seen them. Magic Leap also happens to be the company that has raised the largest amount of venture funding (without actually having a product in the market) in history. $1.4 billion dollars.

Since that initial Magic Leap announcement back in 2014, other companies have slowly begun to show what they are working on in MR. Microsoft has announced and launched for select developers its HoloLens headset (although, confusingly, on its website, the company refers to it as an “AR headset”) (Figure 1-6). Meta, a company that has been working publicly on MR for quite some time and has one of the godfathers of AR/MR research as its chief scientist (Steve Mann), announced its Meta 2 headset (Figure 1-7) at TED in February 2016. DAQRI is another fast-rising player with its construction industry focused “Smart Helmet”—an MR safety helmet with an integrated computer, sensors, and optics. Unlike VR and AR, which do not take into account the user’s environment, MR purposefully blurs the lines between what is real in your field of view (FoV) and what is not in order to create a new kind of relationship and understanding of your environment. This makes MR the most disruptive, exciting, and lucrative of all the reality technologies.

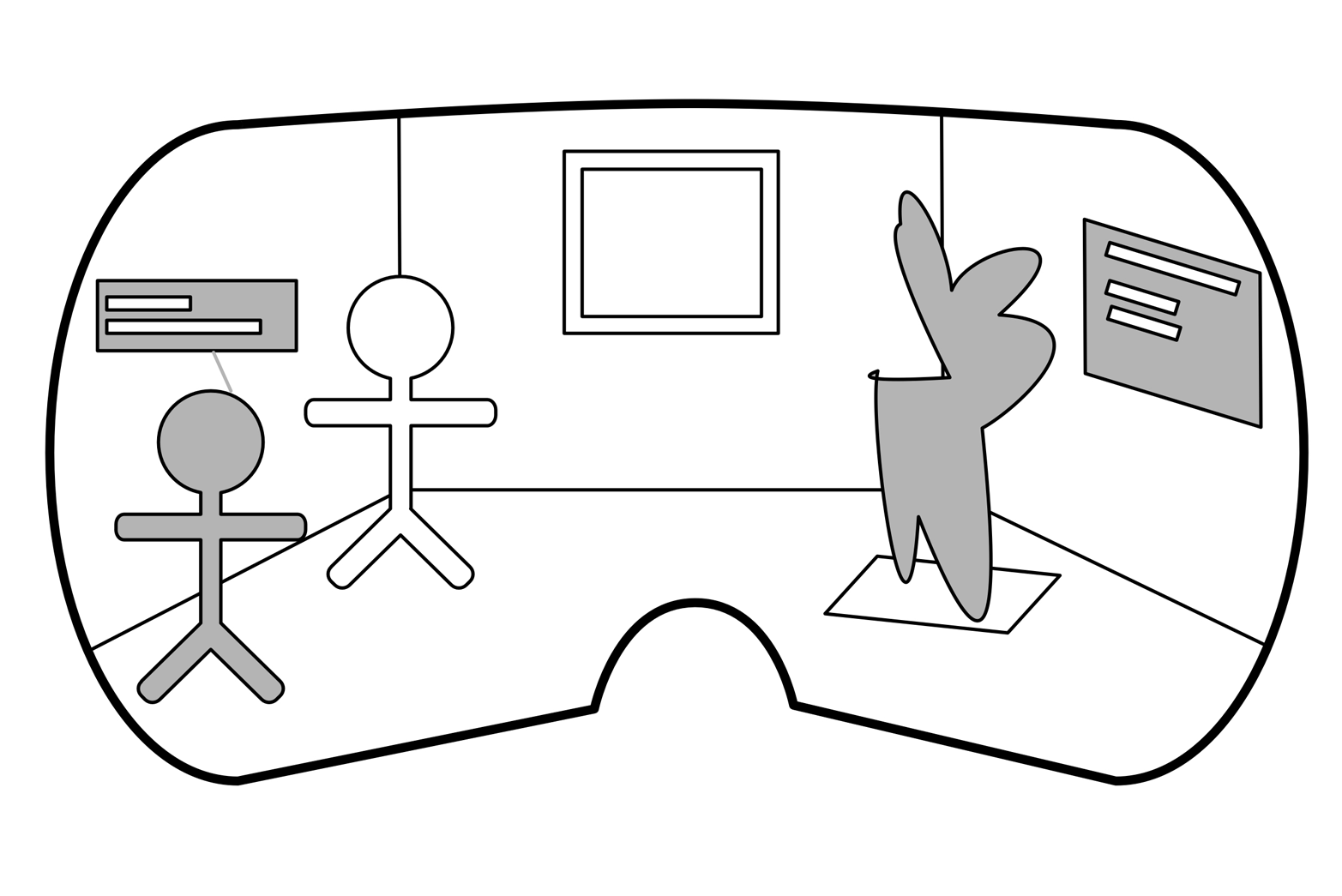

Figure 1-5. Mixed reality—everything you see might or might not be real; with extra data overlaid into your FoV and physically attached to real/not real objects and things, the environment you experience MR in is mapped and directly taken into account

Figure 1-6. Microsoft’s mixed reality headset—the Hololens

Figure 1-7. The Meta 2 mixed reality headset

Pop Culture Attempts at Future Interfaces

MR feels like science fiction. Everyone enjoys a bit of science fiction. And why not? It gives the viewer or reader a guilt-free glimpse into a myriad of possible futures, showing how the world could be. Showing how we could interact with technologies. It’s fun, generally always looks cool and exciting, and also has the useful side effect of subliminally preconditioning the viewer for the eventual introduction of some of these technological marvels. Hollywood always loves a good futuristic user interface. The future interface is also apparently heavily translucent, as seen in everything from Minority Report to Iron Man, Pacific Rim to Star Wars, and many, many more. Clearly, the future will need to be dimly lit to be able to see these displays that float effortlessly in thin air. They are generally made up of lots of boxes that contain teeny, tiny fonts that scroll aimlessly in all directions and contain graphs, grids, and random blinking things that the future human will apparently be able to decipher at a speed that makes me feel old, like I don’t understand anything anymore.

Of course, these interfaces are primarily created for the purpose of entertainment. They rarely take up a large amount of screen time in a film. They are decorative and serve to reinforce a plot line or theme: to make it feel contemporary. They are not meant to be taken seriously, right?

Some films do attempt to make a concerted effort in making believable, usable interfaces. One such recent film, Creative Control (http://www.magpictures.com/creativecontrol/), has its entire story focus around a particular product called “Augmenta,” which is a pair of MR smart glasses that allow the wearer to not only perform the usual types of computing tasks, but also to develop a relationship with an entirely virtual avatar. The interface for the glasses is well thought out, and doesn’t attempt to hide the interactions behind superfluous visual touches. It’s arguably the closest a film has managed to achieve in designing a compelling product that could stand up to the kind of scrutiny a real product must go through to reach the market.

What Kinds of End-Use-Cases Are Best Suited for MR?

So, now that we have all of this technology, what is it actually good for? Although VR is currently enjoying its place in the sun, immersing people in joyful gaming and fun media experiences (and recently even AR has come back into the public consciousness from the immense success of the Pokemon Go smartphone app), MR chooses to walk a slightly different path. Where VR and MR differ in emphasis is that one posits that it is the future of entertainment, whereas the other sees itself as the future of general-purpose computing—but now with a new spatial dimension. MR wants to embellish and outfit your world with not just virtual trinkets, but data, context, and meaning. So, it is only natural to think of MR more as a useful tool in your arsenal; a tool that can help you to get things done better, more efficiently, with more spatial context. It’s a tool that will help you at work and at play (if you have to). Following are some examples of typical use cases that are potentially good fits for MR.

Architecture

Architects follow their own design process that begins with ideation, sketching, and early 3-D mockups. It then moves into 3-D printing or hand-manufacturing models of buildings, and then into high-fidelity formats that can be handed over to developers and engineers to be built. MR is most useful in the earlier stages of 3-D mockups; the ability to quickly view models as if they are already built and share context with other MR-enabled colleagues is something that makes this technology one of the most highly anticipated in the architectural industry.

Training

How much time is spent training new employees for doing jobs out in the field? What if those employees could learn by doing? Wearing an MR headset would put the relevant information for their job right there in front of them. No need to shift context, stop what you are doing, and reference some web page or manual. Keeping new workers focused on the task at hand helps them to absorb the learnings in a more natural way. It’s the equivalent of always having a mentor with you to help when you need it.

Healthcare

We’ve already seen early trials of VR being used in surgical procedures, and although that is pretty interesting to watch, what if surgeons could see the interior of the human body from the outside? One use case that has been brought up many times is the ability for doctors to have more context around the position of particular medical anomalies—being able to view where a cancerous tumor is precisely located helps doctors target the tumor with chemotherapy, reducing the negative impact this treatment can have on the patient. The ability to share that context in real time with other doctors and garner second opinions reduces the risk associated with current treatments.

Education

Magic Leap’s website has an image that shows a classroom full of kids watching sea horses float by while the children sit at their desks in the classroom. The website also has another video that shows a gymnasium full of students sharing the experience of watching a humpback whale breach the gym floor as if it were an ocean. Just imagine how different learning could be if it were fully interactive; for instance, allowing kids to really get a sense of just how big dinosaurs really were, or biology students to visualize DNA sequences, or historians to reenact famous battles in the classroom, all while being there with one another, sharing the experience. This could transform the relationship children have today with the art of learning from being a “push” to learn, into a naturally inquisitive “pull” from the children’s innate desire to experience things.

These kinds of use cases are only the very tip of the iceberg, as we have yet to experience what effect this technology will have across much broader aspects of work. VR has often been referred to as the empathy machine. MR might allow us to collaborate—and thus empathize—together in a much more natural fashion than with other forms of technology.

Get Designing for Mixed Reality now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.