Chapter 4. How to work a tough room

Half of what you pay for at a fancy restaurant isn’t the food. You’re paying its rent, you’re paying for the atmosphere, and you’re paying for the way its service makes you feel. If you’ve ever taken a date somewhere based on where it is, what it looks like, or how it feels to be there, you know this is true. Public speaking is no different; the atmosphere is important to the quality of everyone’s experience. If you had to listen to Martin Luther King, Jr., in a New York City subway station, or Winston Churchill in a highway rest stop bathroom, with all the smells, noises, and rodents those atmospheric monstrosities are known for, you’d be less than pleased. MLK’s most famous speech would go something like this: “I have a…<pauses as the A train speeds by at 110 decibels, audience covering their ears>…drea…oh, nevermind.” His eloquence would be no match for the unpleasant and distractive powers of the environment around him. Place matters to a speaker because it matters to the audience. Old theaters, a university lecture hall, even the steps of the Lincoln Memorial are great places to speak, but most speakers rarely get asked to do their thing in venues this good. Most presentations are given under flickering fluorescent lights inside cramped conference rooms, or in convention halls designed with a thousand other functions in mind, which explains why I know way more than I should about chandeliers.

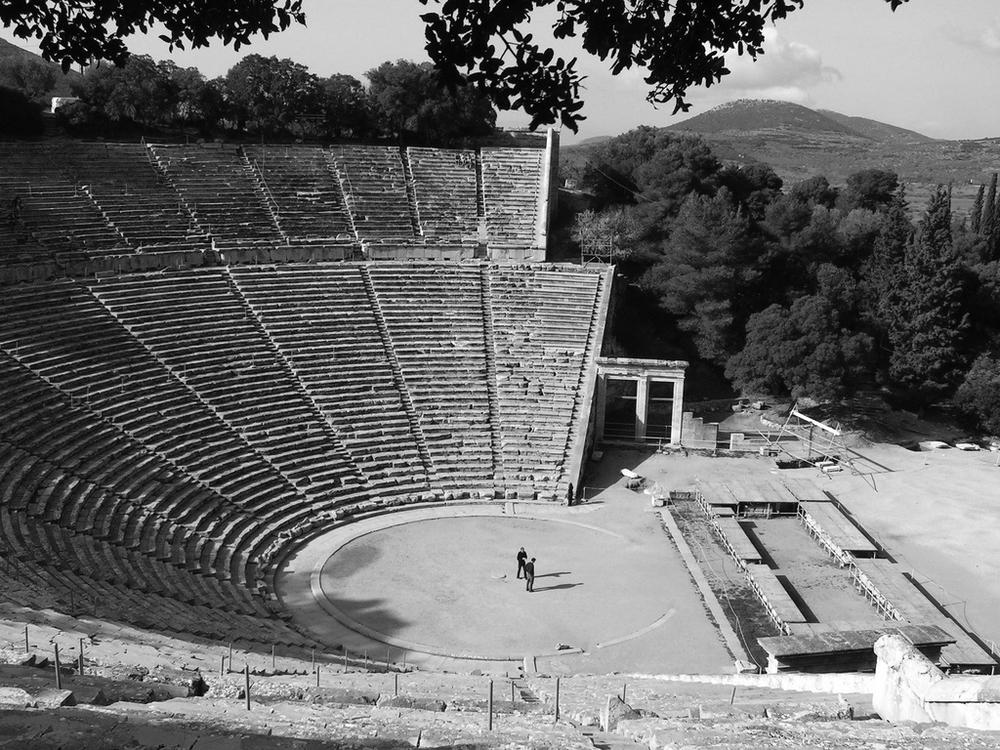

While you are in the audience looking up at the stage, a stage designed to make me easy to see, often I can’t see anything (see Figure 4-1). All the house lights are aimed right at my face. People forget that the room, as bad as it might be, is set up to help the audience see, whereas we speakers are on our own. Whenever you see pictures of a famous person giving a famous lecture, you see the stage exactly the way the person with the best seat in the house saw it. No one else is on stage, and if someone is, he’s not moving around. If President Obama were giving a speech and a dozen people behind him were eating cheeseburgers or playing charades, everyone in the audience would be quite annoyed. But when I look out into the audience, all I see are distractions. I can see and hear the back doors opening and closing with every person arriving late or leaving early. I see the glow of laptops in people’s multitasking eyes. I see cameramen and stage crews moving heavy gear, flashing their lights, and making jokes, all in the back rows behind the crowd, where only I can see. And most depressing of all, on some days, the days I forget to make a sacrifice to the gods of public speaking, all I can see when I look straight ahead is the dizzying glare of the conference hall chandelier. These are the cheap ones, made of grey metal, covered in chipping, peeling gold paint. They hover in the space above the crowd, a place where few in the audience ever look, but precisely where a speaker’s eyes naturally want to go. In a good room, the ceiling is free of distractions; in a bad room, there’s a large glowing ball of stupidity hanging there.

Disco balls work because they’re undeniably silly and make fun of real attempts at decoration, but chandeliers, even the cheap ones I often see, are entirely serious. Despite their phony plastic flame-shaped light bulbs (who was ever fooled by these?), they are a lame attempt to give a room class, a kind of class that—to the disappointment of the owners of these rooms—cannot be obtained by hanging something large and shiny from the ceiling. I’m told these chandeliers are placed in conference halls for one reason: weddings. They want to rent the room out for weddings—the highest marked-up events in the Western world—and somehow without an ugly chandelier in the brochure, they fear they’ll never be chosen as a wedding venue again. Next time you’re at a lecture, check the ceiling. If you spot a chandelier, know that it’s not there for you.

Why pick on a glorified light fixture? Why risk being banned from speaking at chandelier-industry conferences for the rest of my life? Here’s why. Presenters talk about “tough rooms” all the time, usually referring to the audience. They blame the crowd when they should first blame the room. Many challenges are created by the room itself, challenges of atmosphere that change lukewarm crowds into tough ones. Ever try to throw a birthday party in a graveyard or a funeral in an amusement park? Of course not. You’d be set up to fail—unless your family has handfuls of Xanax for breakfast or you’re related to Tim Burton. Most venues for speaking and lecturing in the modern world are dull, grey, uninspiring, poorly lit, generic cubes of space. They are designed to be boring (which is why it’s hard to stay awake during lectures) so they can be used for anything. And like a Swiss Army knife, this means they suck at everything. Your average conference room or corporate lecture hall is bought and sold for its ability to serve many different purposes, though none of them well, which explains my unnatural, and possibly deadly, level of exposure to chandeliers. Blame speakers all you want—we do deserve most of the blame—but some fraction of hate should go to whoever chose the crappy room to stick the audience in. It’s not my choice. If I had my choice, here’s where you’d see me (check out Figure 4-2).

I’d want to be at this Greek amphitheater, in part, because I hear it’s quite nice in Greece, but mostly because the ideal room for a lecture is a theater. It’s crazy, I know, but we solved most lecture-room problems about 2,000 years ago. The Greek amphitheater gets it all just about right, provided it doesn’t rain. Lecture rooms should be a semicircle, not a square. The stage should be a few feet higher than the front row, both to make people on the stage easier to see, but also to help them feel powerful. And most importantly, every row of seats should be higher off the ground than the one before it, giving everyone a clear line of sight. All of these things make it easier for the audience to stay interested and focus its attention on center stage, as well as provide the speaker with natural acoustics.

One of the best lectures I’ve given in recent memory was at Carnegie Mellon University in the Adamson Wing, a theater-sized room that seats maybe 120 (see Figure 4-3).[21] If you put a kegerator inside the lectern and added a remote-controlled shock system that would electrify individual seats on command (an anti-heckler device), it would be perfect.

And, of course, the most overlooked advantage of Greek-style amphitheaters and good university lecture halls? No chandeliers.

Theaters are rare. They cost more to build and to rent, and few conference centers have them. When they do, they’re often reserved for the big-name speakers on the schedule. Everyone else gets the square, dingy, poorly lit loser rooms. I speak in loser rooms all the time. But if you’re invited to give a lecture and get a choice of rooms, ask for the one that’s most theater-like. Even if it’s smaller, even if it’s farther away, the room will score you extra points. I get giddy all over when I know I’m speaking in a room set up to help me connect with the audience. A room free of poles and blind spots, a room with good lighting, a room that’s soundproofed well enough so we don’t hear the traffic outside or the lecture next door. It’s rare, but when it happens, the people who hire me get their money’s worth.

In a square room, there are many problems few talk about. If you’re in an aisle seat at the far right or left of the room, staring straight ahead, you’ll be looking at the front wall. To see what’s going on, you have to turn your head or your body toward the center of the front. You also have to try and look over or between the heads of the people in front of you—which if you’re more than 20 rows back can be impossible. If you can’t see the speaker, why are you there? You might as well watch the lecture on TV in the bar, so you can play lecture drinking games with your friends, such as “ummmster,” where you do a shot of your favorite cocktail every time the speaker says “ummm.” With some speakers, you’ll be passed out in no time.

If you’re in the audience, the angle of your body and the amount of eye contact you make with the speaker might not seem to affect your quality of experience, but for the speaker, it does. When 50, 100, or 5,000 people can give 10% more of their attention and energy to you—whether through their eye contact, posture, or laughter—it makes the difference between feeling confident and feeling lost. One extra pair of friendly eyes, or the visibility of an affirmative nod now and then, changes how any speaker feels. And in a good room—whether you’re at a concert or presentation—energy moves easily between the crowd and the stage.

Even in bad clubs, musicians have many advantages for controlling the energy in a room—bass drums and amplified guitars literally force waves of energy to bounce around, getting people to dance or respond in various other ways. But in a grey, boring square room of right angles on top of right angles—where half the crowd mostly sees the bald spots in the hairlines of the people sitting in front of them, and where instead of a bass drum, they hear the whiny voice of, for example, the head of accounting droning on about the right way to fill out page 9, section F of the new expense reports—the energy in the room is split and fractured well before it leaves the stage. It bounces around, gets eaten by the walls, drained by the dull carpet, smothered by the dim lights, and dies. A speaker, unarmed with a guitar or bongos, is on his own to overcome the deficiencies of the space. Even good speakers are frequently eaten alive by the effects of bad rooms.

The worst situation, even worse than being in a bad room, is being in a big, bad empty room. Speaking in a huge, boring, rectangular, dimly lit room that seats 1,000 people is challenging enough, but with only 100 attendees present, these rooms feel like black holes. Even if you’re screaming, dancing, and juggling knives, it may not be possible to generate enough energy to fill the space. I once saw U2 play at the Meadowlands in New Jersey, which holds 60,000 people. By the end of the show, people were streaming out to beat the traffic, and no matter what Bono did on stage, the stadium was dead. There were still 20,000 dancing people there, but it seemed like the lamest 20,000 people I’d ever seen.

A related personal disaster took place when I spoke at Microsoft’s Tech-Ed conference in Dallas in 1998. I drew the short straw: I had the largest room of the entire massive hotel conference center complex. The ceilings were so high, and the back wall was so distant from the stage, that I actually asked the tech crew if it was a converted aircraft hangar. It must have been used for something other than training events. There was no reason for this room to have the scale it did, other than to torture public speakers. The crew looked up at the ceiling when I asked, and were sort of surprised there was a ceiling there at all. They never thought to look up, as they spend most of their time just trying to fix all the stuff that breaks down at ground level. I should have told them about how stars hover in the night sky—it would have blown their minds.

The room was set with chairs for over 2,000 people. When I heard this, my ego lit up: 2,000 people? To see me? Wow. I must be super cool. But as the countdown timer ticked away—20 minutes, 10 minutes, 5—and I’d spent all that time staring out at a sea of empty seats, I was mortified. I didn’t want to go on. I’d never seen so many empty chairs all in one place. Where did they keep them? There must have been a huge storeroom just for these chairs. How utterly pathetic for someone to have spent an afternoon arranging them all, only for those chairs to sit empty and unloved. And how depressing that I was the person who had failed to fill them.

With a minute to go, a few people were seated here and there. A handful more walked in from the back exit, like little ants entering my zip code–sized room (you always get a few at the last minute). It was nice to see them, but they quickly disappeared into the cave-like darkness between the aisles. With 20 seconds to go, I noticed one guy up front, finally aware of the tumbleweeds drifting past him, grab his things and scurry toward the door. So much for him. Five seconds. The house lights came up and with them came a wave of heat over my face and arms. The few pairs of eyes in the room were now all on me. It was time to start.

What could I do? Was there anything that could be done? My body chose to panic. Having panicked before, I knew the only trick was to start, as fear comes from what you imagine might happen instead of what actually is happening, and the longer you wait, the worse it gets. The only way to kill this evil feedback loop is to just do it, so I forced myself to begin. And I sucked. For an hour I sucked—an endless hour of misery, speaking into the Grand Canyon of rooms, with each and every word traveling slowly across a sea of empty chairs. I heard every word twice, once when I said it, and two seconds later when it echoed against the back wall, unimpeded by the sound-absorbing powers of an actual crowd. When I finished, I sulked my way to a dark corner of the hotel bar, hid behind a row of beers, and hoped not to be seen.

The solution to this, and to many other tough room problems, rests on the density theory of public speaking, a theory I discovered one day after repeating the Dallas experience in some other city, with some other embarrassingly small crowd in a ridiculously large room. I realized that the crowd size is irrelevant—what matters is having a dense crowd. If ever you face a sparsely populated audience, do whatever you have to do to get them to move together. You want to create a packed crowd located as close as possible to the front of the room. This goes against most speakers’ instincts, which push them to just go on with the show and pretend not to notice it feels like they’re speaking at the Greyhound bus station at 3 a.m. on Christmas morning.

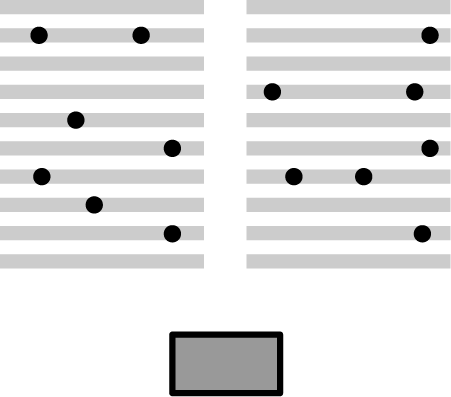

Those few people in the audience know as well as you do that the room is empty, and if you act like you don’t notice, they’ll know you’re full of shit before you get five minutes into your talk. Audiences, even tough crowds, genuinely want to help you, but no one in the audience can do anything about bad energy. Only two people in the room have that control: the host and the speaker. The host, a person who likely knows little about public speaking (much less the density theory), and who probably has 25 other event problems more important than your empty room, is unlikely to be of use. Hell, he chose to put you in the room of certain death to begin with. So all hope rests in the hands of whoever has the microphone, and that’s you (see Figure 4-4).

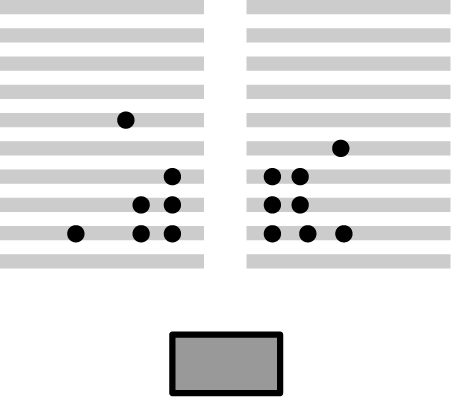

Forty-five people in a 2,000-person room is not a crowd, it’s the equivalent devastation of a neutron bomb. This means the first move is to forget the 2,000 seats. Forget the empty rows and dead spaces. Imagine a smaller room inside the big one that seats about 50 people (see Figure 4-5). Make the room your own by asking the attendees to gather into that more intimate space. If you leave them scattered in the wasteland of empty seats, they will feel like lonely losers. They will feel embarrassed for having chosen to come see you instead of any of a thousand other nonembarrassing things they could have done with their hour. If you pack them together, at least they’ll know they’re not the only losers who decided to come hear you. They are now losers with loser friends, which—all things considered—is much better than being a loser without any friends at all. They are, in fact, your losers, so you should treat them well.

The tricky part is getting people to move. We are a lazy species. I know once I’m seated I’m not very interested in getting up just to sit down again. But the fact is, all of us do what people in authority tell us to do, especially in lecture halls. We have spent our lives listening to people at the front of crowded rooms telling us to stand up, sit down, sing songs, close our eyes, play “Simon Says,” repeat national anthems, and a thousand other stupid things we’d never agree to do if we weren’t being dictated to by someone with a microphone. It doesn’t matter where you are or how scared the crowd suspects you might be, if you have the mike and explain the situation with a smile, when you ask them nicely to stand up and move forward, they will. Make it a game. Offer a prize to the person who gets up first. Ask the audience members if they need more exercise today, and when they all raise their hands (people who go to lectures and conferences always crave exercise), tell them you have just the thing for them to do. You might eat a few minutes of your time, but it’s worth it if you have a long session. And whoever speaks to the same crowd after you will be grateful.

The few that don’t oblige should be left in the back of the room anyway. There’s no law stating that you must treat everyone in the audience the same. Give preferential treatment to the people who respond to your requests. By making them move, you’ve done a few other beneficial things. They’ve now invested something in you, and you will have their attention for at least the next two minutes. You spoke the truth about the uncomfortable nature of the room, and people will respect your honesty and willingness to take action to fix it. And for your sake, you’ve identified the leaders and fans: they’re the ones who got up first. These are the people most interested in you and what you have to say. If there are any allies in the crowd—the people first to applaud or ask a question—you now know who they are.

Most importantly, the density theory amplifies your energy. We’re social creatures. If five people—or even dogs, raccoons, or other social animals—get together, they start to behave in shared ways. They make decisions together, they move together, and most importantly, they become a kind of short-term community. With a tightly packed crowd, if I make one person laugh, nod his head, or smile, the people directly adjacent will notice and be slightly more prone to do it themselves. TV sitcoms have laugh tracks for this reason: we respond to what the crowd around us is doing. Even simply having the woman next to you listening with her full attention changes the atmosphere for the better, versus sitting next to an annoying dude checking his email who doesn’t look up once. The size of the room or the crowd becomes irrelevant as long as the people there are together in a tight pack, experiencing and sharing the same thing at the same time.

There are many similar adjustments a speaker can make to a room. Turn up the lights if it feels like you’re in a cave. Ask for a wireless microphone or bring your own if you hate being tied to the lectern. If you spot someone stuck behind a pole or standing in the back, offer him a seat near the front that he might not have noticed was empty. Always travel with a remote for your laptop so you can move to a better spot if the lectern was placed in some stupid back corner of the stage. Ask the crowd if they’re too cold or too warm, and then, on the mike, ask the organizers to do something about it (even if they can’t, you look great by being the only speaker to give a care about how the audience is feeling). There are always little things you can do—that don’t require the construction of your own private lecture theater—to improve how the room feels. When you have the microphone, it’s your room—do whatever you’d like to enhance the audience’s experience.

Failing to own your turf is the big mistake that can create a tough crowd. If I show up five minutes before I start speaking, I have no idea what the vibe is like. Every audience is different for a thousand reasons, from what the traffic was like that morning to what sports team won or lost the night before to what community politics are happening. If I just show up right before my talk, I can’t sort out how much of it has to do with me as opposed to general hatred for the world at large. Taking responsibility for the crowd means showing up to the room early enough to at least hear the previous speaker. Sometimes you’ll hear a joke or comment in the previous talk that you can pick up on, or know to avoid, given that it’s been used before. If the speaker was awesome but only got cold stares from the crowd, you know something is up that’s larger than you or the other speaker. But if he does well and gets great energy and strong applause, yet you go down in flames, you know it’s not the audience—it’s you.

Speaking in foreign countries makes this all too clear. You have no idea what a tough crowd is until you’ve spoken in Sweden, Japan, or scores of other countries where laughing, joking, and yelling out support during a presentation are cultural taboos. And unless you speak the local language, you’re being translated, which means the audience doesn’t know what you said—or what the translator decided you said—until about 10 seconds after you’ve said it. When I spoke in Moscow, live translated just like at the United Nations, the audience was awesome, but I didn’t know why they were laughing until the translator explained it through my earpiece. For long, horrible moments, I was afraid they were laughing at or heckling me, rather than supporting what I’d said. After speaking through live translation a few times, presenting to a rowdy crowd is a breeze if they speak your native language.

If all else fails—you know the audience hates you and your point of view—seek out the person who hates you the least. All rooms, no matter how tough, have one person who hates you the least. Even if you’re a Flying Spaghetti Monster disciple speaking at the Vatican, someone in that room will hate you less than everyone else.[22] Maybe it’s because he thinks you’re cute or he’s amused by how scared you are to be there, but he’s your best chance. If you are going to get a first smile, a nod of support, or a round of applause, it’s going to come from him. Once you find that one person, use him as your base. Don’t ignore everyone else, but know where to look for support. Or, if you arrive early, take the initiative to talk to people in the crowd and find some supporters. Ask them to move up front. Alternatively, you might discover the one person who has a really good reason to hate you and make sure not to let him ask the first question during Q&A.

Sometimes the tough crowd is entirely imagined and then created by the speaker, who, realizing the audience is hostile, blames them. What kind of idiot does this sort of thing? My kind of idiot. The first big lecture I gave was in 1996. It was an internal lecture at Microsoft to about 200 engineers and managers. At the arrogant age of 24, I was so certain the crowd would tear me to pieces that I made sure they never had a chance. I spoke in my fastest New-Yorker-who-wants-to-kick-your-ass tone, never smiled, and made clear my unwillingness to let anyone in the audience enjoy anything from the moment I opened my mouth. Why did I do all this? Why did I come off so unpleasant? I was terrified. And as an arrogant and frightened young man, I took it out on the people I most feared. I watched the video of this talk and destroyed it afterward. That’s how ridiculous my behavior was.

In the act of protecting myself from what I thought would be a hostile, critical, skeptical audience, I set about on the one course most likely to create the thing I was trying to avoid. I’m sure this happens often: being paranoid has strikingly good odds of creating what we’re afraid of, perpetuating the paranoia. If I hadn’t later seen that video of my performance, I wouldn’t have the life I have now. I would always have thought I was responding to the crowd, not that it was responding to me. I would have continually wondered why my crowds were so unpleasant, and eventually given up. Now I know I have to embody what I want the audience to be. If I want them to have fun, I have to have fun. If I want them to laugh, I have to laugh. But it has to be done in a way they can connect with, which is hard to do. A drunken toast at a wedding is often great fun for the toaster but miserable for everyone else. But great speakers are connection-makers, sharing an authentic part of themselves to create a singular, positive experience for the audience.

One unusual way to think about tough crowds is that a crowd has to be interested in you to hate you. A hostile crowd gives you more energy to work with than an indifferent one. Giving a lecture to a room full of people in comas, literally in hospital beds, wired up to IVs filled with various horse tranquilizers, has a zero percent chance of them being interested in you. But if people are angry or rowdy, it means they care about something. They have some energy they are willing to contribute, for better or for worse. If you can figure out what it is they’re interested in, preferably early on, it’s possible to connect with them. Find common ground and bring it to the surface. Their hate will quickly turn to respect, as you’ve said the thing on stage they’ve never heard someone like you say before. After watching and giving hundreds of lectures, I’ve learned that by far the thing people seem angriest about is dishonesty. Show some integrity by speaking the truth on the very thing that angers them, or even acknowledging it in a heartfelt way, and you will score points. People with the courage to speak the truth into a microphone are exceptionally rare.

Few people know that Dale Carnegie’s most popular book, How to Win Friends & Influence People (Pocket), which is one of the bestselling self-help books in history, received significant backlash from the press and cultural elites of its time. Carnegie was ridiculed in editorials and cartoons, and mocked at colleges and universities, for offering over-simplified and sappy advice (in the same way Deepak Chopra and Dr. Phil are made fun of today). He was invited to speak at the Dutch Treat Club in New York City, an elite group of publishers, editors, and advertising men, the kind of cynical, tough-minded folks most critical of his work. Despite warnings from his advisors, he chose to speak anyway, and here’s what he said:

I know there’s considerable criticism of my book. People say I’m not profound and there’s nothing in it new to psychology and human relations. This is true. Gentlemen, I’ve never claimed to have a new idea. Of course I deal with the obvious, I present, reiterate, and glorify the obvious—because the obvious is what people need to be told. The greatest need of people is to know how to deal with other people. This should come naturally to them, but it doesn’t. I am told that you are a hostile audience. But I plead “not guilty.” The ideas I stand for are not mine. I borrowed them from Socrates. I swiped them from Chesterfield. I stole them from Jesus, and I put them in a book. If you don’t like their rules, whose would you use? I’d be glad to listen.[23]

According to one report, he received a huge round of applause. While I’m not a big fan of that book, I am a fan of this story. He handled a tough crowd in a bold, smart, and honest way.

However, on some days, no matter what you do, some folks will hate you anyway. Occasionally, I encounter people who love to hate, or I just rub them the wrong way for reasons I can’t explain. I once had a professor at a university I was invited to lecture at interrupt me three times before I moved past my first slide. Minutes later, after long glares and inventively loud sighs, he got up and left.[24] Could I have done anything differently? I didn’t think so. Sometimes a person just doesn’t like you and takes pleasure in hating you. If I had tried to please him, perhaps I’d just make someone else equally mad. I don’t mind being hated, since I hate some things and people, too. But when it disrupts the audience, it’s now ruining something the rest of the room seems to enjoy. Once the professor left, he spared me the challenge of having to ask him to shut up or leave, which I would have had to do if he continued.

For that, perhaps I should be grateful. It’s easy to forget that most people feel trapped in their seats. If they want to leave, they can’t bear the attention they’d get for standing up and scrambling over people’s knees to get to the aisle. If someone is unhappy, I’m happy to see him go rather than spoil the energy for everyone else. I don’t find it rude at all—it’s a blessing. A small crowd of 5 interested people looks bad but is a better situation than 50 people who want to leave but won’t.

If you’re truly afraid you will be on hostile turf, some extra legwork can relieve your fears. Ask your host how large the crowd tends to be and what common questions might get asked. Request the names of three people to interview who are representative of the crowd you will speak to. See if your fears are real or imagined. Then, when giving your talk, make sure to mention, “Here are the three top complaints I heard from my research with Tyler, Marla, and Cornelius.” Including the audience in your talk will score you tons of points. Few people ever do this, and if the rest of the crowd disagrees with Tyler, Marla, or Cornelius, they can sort that out on their own after you leave.

[21] As an alumni of Carnegie Mellon University, I got a special thrill from speaking in a room I’d fallen asleep in many times. However, the bigger rooms in Doherty Hall should be studied for their sleep-inducing powers

[22] For information on the Church of the Flying Spaghetti Monster, see http://www.venganza.org/about/.

[23] From The Man Who Influenced Millions, Giles Kemp and Edward Claflin (St. Martin’s Press), p. 154.

[24] After the lecture, his students apologized for his behavior; apparently, I was not the first to be received so warmly. I politely contacted him afterward to see what he was upset about. His response was to offer to send me some of his books so I “might learn something.”

Get Confessions of a Public Speaker now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.