HTML forms are the user interface that provides input to your CGI scripts. They are primarily used for two purposes: collecting data and accepting commands. Examples of data you collect may include registration information, payment information, and online surveys. You may also collect commands via forms, such as using menus, checkboxes, lists, and buttons to control various aspects of your application. In many cases, your forms will include elements for both: collecting data as well as application control.

A great advantage of HTML forms is that you can use them to create a frontend for numerous gateways (such as databases or other information servers) that can be accessed by any client without worrying about platform dependency.

In order to process data from an HTML form, the browser must send the data via an HTTP request. A CGI script cannot check user input on the client side; the user must press the submit button and the input can only be validated once it has travelled to the server. JavaScript, on the other hand, can perform actions in the browser. It can be used in conjunction with CGI scripts to provide a more responsive user interface. We will see how to do this in Chapter 7.

This chapter covers:

How form data is sent to the server

How to use HTML tags for writing forms

How CGI scripts decode the form data

In the last couple of chapters, we have referred to the options that a browser can include with an HTTP request. In the case of a GET request, these options are included as the query string portion of the URL passed in the request line. In the case of a POST request, these options are included as the content of the HTTP request. These options are typically generated by HTML forms.

Each HTML form element has an associated name and value, like this checkbox:

<INPUT TYPE="checkbox" NAME="send_email" VALUE="yes">

If this checkbox is checked, then the option

send_email with a value of yes

is sent to the web server. Other form elements, which we will look at

in a moment, act similarly. Before the browser can send form option

data to the server, the browser must encode it. There are currently

two different forms of encoding form data. The default encoding,

which has the

media

type of application/x-www-form-urlencoded, is used

almost exclusively. The other form of encoding,

multipart/form-data,

is

primarily used with forms which allow the user to upload files to the

web server. We will look at this in Section 5.2.4.

For now, let’s look at how

application/x-www-form-urlencoded works. As we

mentioned, each HTML form element has a name and a value attribute.

First, the browser collects the names and values for each element in

the form. It then takes these strings and encodes them according to

the same rules for encoding

URL text that we discussed in Chapter 2. If you recall, characters that have special

meaning for

HTTP are replaced with a percentage

symbol and a two-digit hexadecimal number;

spaces are replaced with

+. For example, the string “Thanks for the

help!” would be converted to

“Thanks+for+the+help%21”.

Next, the browser joins each name and value with an equals sign. For example, if the user entered “30” when asked for the age, the key-value pair would be “age=30”. Each key-value pair is then joined, using the “&” character as a delimiter. Here is an example of an HTML form:

<HTML>

<HEAD>

<TITLE>Mailing List</TITLE>

</HEAD>

<BODY>

<H1>Mailing List Signup</H1>

<P>Please fill out this form to be notified via email about

updates and future product announcements.</P>

<FORM ACTION="/cgi/register.cgi" METHOD="POST">

<P>

Name: <INPUT TYPE="TEXT" NAME="name"><BR>

Email: <INPUT TYPE="TEXT" NAME="email">

</P>

<HR>

<INPUT TYPE="SUBMIT" VALUE="Submit Registration Info">

</FORM>

</BODY>

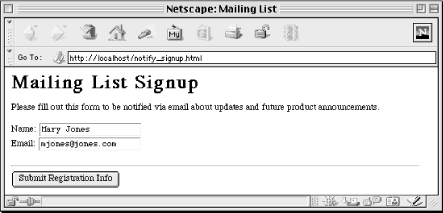

</HTML>Figure 4.1 shows how the form looks in Netscape with some sample input.

When this form is submitted, the browser encodes these three elements as:

name=Mary+Jones&email=mjones%40jones.com

Since the request method is POST in this example, this string would be added to the HTTP request as the content of that message. The HTTP request message would look like this:

POST /cgi/register.cgi HTTP/1.1 Host: localhost Content-Length: 67 Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded name=Mary+Jones&email=mjones%40jones.com

If the request method were set to GET, then the request would be formatted this way instead:

GET /cgi/register.cgi?name=Mary+Jones&email=mjones%40jones.com HTTP/1.1 Host: localhost

A full discussion of HTML and user interface design is clearly beyond the scope of this book. Many other books are available which discuss these topics at length, such as HTML: The Definitive Guide, by Chuck Musciano and Bill Kennedy (O’Reilly & Associates, Inc.). However, many of these other resources do not discuss the relationship between HTML form elements and the corresponding data sent to the web server when a form is submitted. So let’s run through a quick review of HTML form elements before we see how CGI scripts process them.

Before we get going, Table 4.1 shows a short list of all the available form tags.

Table 4-1. HTML Form Tags

|

Form Tag |

Description |

|---|---|

|

<FORM ACTION="/cgi/register.cgi” METHOD="POST"> |

Start the form |

|

<INPUT TYPE="text” NAME="name” VALUE="value” SIZE="size"> |

Text field |

|

<INPUT TYPE="password” NAME="name” VALUE="value” SIZE="size"> |

Password field |

|

<INPUT TYPE="hidden” NAME="name” VALUE="value” > |

Hidden field |

|

<INPUT TYPE="checkbox” NAME="name” VALUE="value” > |

Checkbox |

|

<INPUT TYPE="radio” NAME="name” VALUE="value” > |

Radio button |

|

<SELECT NAME="name” SIZE=1> <OPTION SELECTED>One</OPTION> <OPTION>Two</OPTION> : </SELECT> |

Menu (drop-down) |

|

<SELECT NAME="name” SIZE=n MULTIPLE> <OPTION SELECTED>One</OPTION> <OPTION>Two</OPTION> : </SELECT> |

Select box |

|

<TEXTAREA ROWS=yy COLS=xx NAME="name"> : </TEXTAREA> |

Multiline text field |

|

<INPUT TYPE="submit” NAME="name” VALUE="value” > |

Submit button |

|

<INPUT TYPE="image” SRC="/image.gif” NAME="name” VALUE="value"> |

Image button |

|

<INPUT TYPE="reset” VALUE="Message!"> |

Reset button |

|

</FORM> |

End the form |

All forms begin with a <FORM> tag and end with a </FORM> tag:

<FORM ACTION="/cgi/register.cgi" METHOD="POST"> . . . </FORM>

Submitting a form generates an HTTP request just like clicking on a hyperlink, but a request generated by a form is almost always directed at a CGI script (or a similar dynamic resource). You specify the format of the HTTP request via attributes of the <FORM> tag:

- METHOD

METHOD specifies the HTTP request method used when calling the CGI script. The options are GET and POST, and they correspond to the request methods we’ve already seen as part of the HTTP request line, although they are not case-sensitive here. If the method is not specified, it defaults to GET.

- ACTION

ACTION specifies the URL of the CGI script that should receive the HTTP request made by the CGI script. By default, it is the same URL from which the browser retrieved the form. You are not limited to using a CGI program on your server to decode form information; you can specify a URL of a remote host if a program that does what you want is available elsewhere.

- ENCTYPE

ENCTYPE specifies the media type used to encode the content of the HTTP request. Because GET requests do not have a body, this attribute is only meaningful if the form has POST as its method. This attribute is rarely included since the default—application/x-www-form-urlencoded—is appropriate in almost all cases. The only real reason to specify another media type is when creating a form that accepts file uploads. File uploads must use multipart/form-data instead. We will discuss this second option later.

- onSubmit

onSubmit is a JavaScript handler, and it specifies the JavaScript code that should be executed when the form is submitted. If the code returns a false value, it will cancel the submission of the form. Throughout this chapter we will review which JavaScript handler is associated with each HTML form element, but we won’t cover JavaScript in detail until Chapter 7.

A document can consist of multiple forms, but one form cannot be nested inside another form.

The <INPUT> tag generates a wide array of form widgets. They are differentiated by the TYPE attribute. Each <INPUT> tag has the same general format:

<INPUT TYPE="text" NAME="element_name" VALUE="Default value">

Like <BR>, this tag has no closing tag. The basic attributes that all input types share are as follows:

- TYPE

TYPE determines the type of the input widget to display. A presentation of each type follows this section.

- NAME

The NAME attribute is important because the CGI script uses this name to access the value of those elements that are submitted.

- VALUE

The meaning of VALUE varies depending on the type of the input element. We will discuss this property in our discussion of each type.

Let’s look at each of the input types.

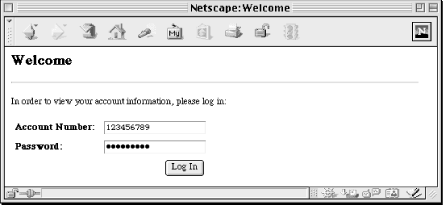

One of the most basic uses of the <INPUT> tag is to generate a text fields where users may enter a line of data (see Figure 4.2). Text fields are the default input type; if you omit the TYPE attribute, you will get a text field. The HTML for a text field looks like this:

<INPUT TYPE="text" NAME="quantity" VALUE="1" SIZE="3" MAXLENGTH="3">

Here are the attributes that apply to text fields:

- VALUE

The VALUE of text fields is the default text displayed in the text field when the form is initially presented to the user. It defaults to an empty string. The user can edit the value of text fields; updates change what is displayed as well as the value passed when the form is submitted.

- SIZE

The SIZE attribute specifies the width of the text field displayed. It roughly corresponds to the number of characters the field can hold, but this is generally only accurate if the element is surrounded by <TT> or <PRE> tags, which indicate that a monospace font should be used. Unfortunately, Netscape and Internet Explorer render the width of fields very differently when monospaced fonts are not used, so certainly test your form with both browsers. The default SIZE for text fields is 20.

- MAXLENGTH

The MAXLENGTH attribute specifies the maximum number of characters that a text field can hold. Browsers generally do not allow users to enter more characters than this. Because the size of text fields can vary with variable-width fonts, it is possible to set MAXLENGTH and SIZE to the same value and yet have a field that appears too large or too small for that number of characters. A text field can have a MAXLENGTH set to more characters than its SIZE can display. By default, there is no specified limit on the size of text fields.

- onFocus, onBlur, onChange

The JavaScript handlers are onFocus, onBlur, and onChange, which are called when the text field has focus (the input cursor is in the field), loses focus (the cursor moves out of the field), and when the value of the field changes, respectively.

A password field is similar to a text field, except that instead of displaying the true value of the field, the browser represents each character with an asterisk or bullet (refer back to Figure 4.2):

<INPUT TYPE="password" NAME="set_password" VALUE="old_password" SIZE="8" MAXLENGTH="8">

This field does not provide any true security; it simply provides basic protection against someone looking over the shoulder of the user. The value is not encrypted when it is transferred to the web server, which means that passwords are displayed as part of the query string for GET requests.

All the attributes that apply to text fields also apply to password fields.

Hidden fields are not visible to the user. They are generally used only with forms which are themselves generated by a CGI script and are useful for passing information between a series of forms:

<INPUT TYPE="hidden" NAME="username" VALUE="msmith">

Like password fields, hidden fields provide no security. Users can view the name and value of hidden fields by viewing the HTML source in their browsers.

We’ll discuss hidden fields in much more detail in our discussion of maintaining state in Chapter 11.

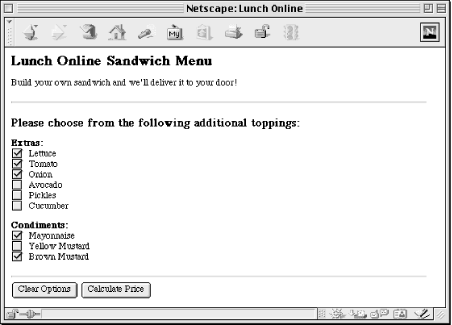

Checkboxes are useful when users simply need to indicate whether they desire an option. See Figure 4.3.

The user can toggle between two states on a checkbox: checked or unchecked. The tag looks like this:

<INPUT TYPE="checkbox" NAME="toppings" VALUE="lettuce" CHECKED>

In this example, if the user selects the checkbox, then “toppings” returns a value of “lettuce”. If the checkbox is not selected, neither the name nor the value is returned for the checkbox.

It is possible to have multiple checkboxes use the same name. In fact, this is not uncommon. The most typical situation in which you might do this is if you have a dynamic list of related options and the user could choose a similar action for all of them. For example, you may wish to list multiple options this way:

<INPUT TYPE="checkbox" NAME="lettuce"> Lettuce<BR> <INPUT TYPE="checkbox" NAME="tomato"> Tomato<BR> <INPUT TYPE="checkbox" NAME="onion"> Onion<BR>

If, however, the CGI script does not need to know the name of each of the options in order to perform its task, you may wish to do this instead:

<INPUT TYPE="checkbox" NAME="toppings" VALUE="lettuce"> Lettuce<BR> <INPUT TYPE="checkbox" NAME="toppings" VALUE="tomato"> Tomato<BR> <INPUT TYPE="checkbox" NAME="toppings" VALUE="onion"> Onion<BR>

If someone selects “lettuce” and “tomato” but

not “onion”, then the browser will encode this as

toppings=lettuce&toppings=tomato. The CGI

script can process these multiple toppings, and you may not need to

update the CGI script if you later add items to the list. Attributes

for checkboxes include:

- VALUE

The VALUE attribute is the value included in the request if the checkbox is checked. If a VALUE attribute is not specified, the checkbox will return “ON” as its value. If the checkbox is not checked, then neither its name nor value will be sent.

- CHECKED

The CHECKED attribute indicates that the checkbox should be selected by default. Omitting this attribute causes the checkbox to be unselected by default.

- onCheck

Checkboxes also take the onCheck attribute, which indicates the JavaScript code that should be executed when the checkbox is selected.

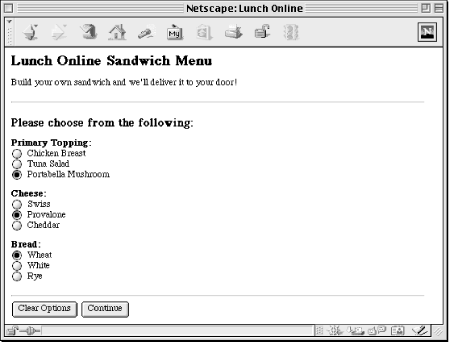

Radio buttons are very similar to checkboxes except that any group of radio buttons that share the same name are exclusive: only one of them may be selected. See Figure 4.4.

The tag is used just like a checkbox:

<INPUT TYPE="radio" NAME="bread" VALUE="wheat" CHECKED> Wheat<BR> <INPUT TYPE="radio" NAME="bread" VALUE="white"> White<BR> <INPUT TYPE="radio" NAME="bread" VALUE="rye"> Rye<BR>

In this example, “wheat” is selected by default. Selecting “white” or “rye” will cause “wheat” to be unselected.

Although you may omit the VALUE attribute with checkboxes, doing so with radio buttons is meaningless since the CGI script will not be able to differentiate between different radio buttons if they all return “ON”.

Using the CHECKED attribute with multiple radio buttons with the same name is not valid. Browsers will generally render both as selected, but they will be unselected as soon as the user selects a different option and the user will be unable to return the form to this initial state (unless it has a reset button of course).

Radio buttons use the same attributes as checkboxes.

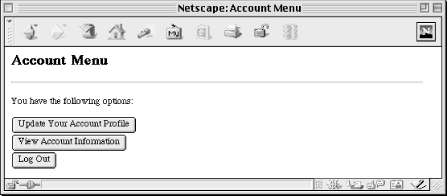

A submit button does just what the name implies. It submits the contents of the form (see Figure 4.5). When the user clicks on a submit button, the browser runs any associated JavaScript onSubmit handler, formats an HTTP request according to the form method and form encoding type, then sends this request to the URL specified by the form action. The result is then displayed as a new web page.

The HTML for a submit button looks like this:

<INPUT TYPE="submit" NAME="submit_button" VALUE="Submit the Form">

Virtually all forms have a submit button, and you can have multiple submit buttons on one form:

<INPUT TYPE="submit" NAME="option" VALUE="Option 1"> <INPUT TYPE="submit" NAME="option" VALUE="Option 2">

Only the name and value of the submit button clicked is included in the form submission. Here are the attributes it supports:

- VALUE

The VALUE attribute for submit buttons specifies the text that should be displayed on the button as well as the value supplied for this element when the form is submitted. If the value is omitted, browsers supply a default label—generally “Submit”—and refrain from submitting a name and value for this element.

- onClick

Submit buttons may have an onClick JavaScript handler, which specifies the code to execute if the user clicks the button. Returning a false value from this code cancels the submit operation.

A reset button allows users to reset the value of all the fields in a form to their default values. From the user’s perspective, it generally accomplishes the same thing as reloading the form but is much faster and more convenient. Because the browser accomplishes this event without consulting the web server, CGI scripts never respond to it. The HTML tag looks like this:

<INPUT TYPE="reset" VALUE="Reset the form fields">

You may have multiple reset buttons on the same form, although this would almost certainly be redundant.

- NAME

You may specify a NAME for reset buttons, but neither the name nor the value is ever passed to a CGI script. Thus, the name is only useful to JavaScript code.

- VALUE

The VALUE attribute specifies the text label that should appear on the button.

- onClick

Like submit buttons, reset buttons may have an onClick attribute that specifies the JavaScript code to execute if a user clicks on the button; returning false from this code will cancel the reset operation.

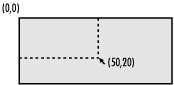

You can also have images as buttons. Image buttons function as submit buttons but give you much more flexibility over how the button looks. Keep in mind that users are generally used to having buttons displayed a particular way by the browser and operating system, and a button in a different format may be confusing to a novice. The HTML for an image button tag looks like this:

<INPUT TYPE="image" SRC="/icons/button.gif" NAME="result" VALUE="text only">

Graphical and text-only browsers treat this element very differently. A text-only browser, such as Lynx, sends the name and value together like most other form elements:

result=text+only

However, a graphical browser, like Netscape and Internet Explorer, send the coordinates where the user clicked on the image in addition to the name of the button. The value is not sent. These coordinates are measured in pixels from the upper-left corner of the image (see Figure 4.6).

In this example, a graphical browser would submit:

action.x=50&action.y=20

Here are the attributes for image buttons:

- VALUE

The VALUE attribute is sent as the value for this element by text browsers.

- SRC

The SRC attribute specifies the URL to the image displayed for the button, just as it does in the more common <IMG> tag (if the <IMG> tag looks unfamiliar to you, it’s because you probably only recognize it when combined with the SRC attribute: <IMG SRC=...>).

- onClick

This attribute behaves just as it does with standard submit buttons.

The last type of button is just that—a button; it has no special function. To avoid confusing this button with the other button types, we will refer to it as a plain button. A plain button tag looks like a submit or reset button:

<INPUT TYPE="button" VALUE="Click for a greeting..." onClick="alert( 'Hello!' );">

The name and value of a plain button is never passed to a CGI script.

Because a plain button has no special action, it is meaningless

without an onClick attribute:

- NAME

The NAME attribute is never sent as part of a request, so it is only useful to JavaScript code.

- VALUE

The VALUE attribute specifies the name of the button.

- onClick

The onClick attribute specifies the code to run when the button is clicked. The code’s return value has no effect because plain buttons do not cause other behavior.

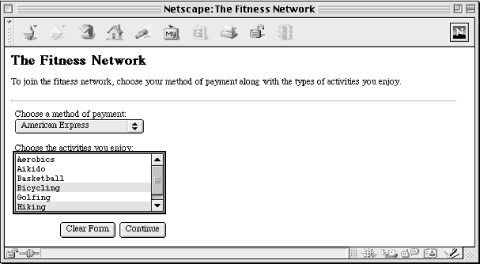

The <SELECT> tag is used to create a list for users to choose from. It can create two different elements that look quite different but have similar function: a scrolling box or a menu (also commonly referred to as a drop-down). Both elements are displayed in Figure 4.7. Unlike the <INPUT> elements, <SELECT> tags have an opening as well as a closing tag.

Here is an example of a menu:

Choose a method of payment: <SELECT NAME="card" SIZE=1> <OPTION SELECTED>American Express</OPTION> <OPTION>Discover</OPTION> <OPTION>Master Card</OPTION> <OPTION>Visa</OPTION> </SELECT>

Here is an example of a scrolling box:

Choose the activities you enjoy: <SELECT NAME="activity" SIZE=4 MULTIPLE> <OPTION>Aerobics</OPTION> <OPTION>Aikido</OPTION> <OPTION>Basketball</OPTION> <OPTION>Bicycling</OPTION> <OPTION>Golfing</OPTION> <OPTION>Hiking</OPTION> ... </SELECT>

Scrolling boxes may optionally allow the user to select multiple

entries. Multiple options are encoded as separate name-value pairs,

as if they had been entered by multiple form elements. For example,

if someone selects Aikido, Bicycling, and Hiking, the browser will

encode it as activity=Aikido&activity=Bicycling& activity=Hiking.

Attributes for the <SELECT> tag are:

- SIZE

The SIZE attribute determines the number of lines visible in the list. Specifying 1 for the SIZE indicates that the list should be a menu instead.

- MULTIPLE

The MULTIPLE attribute allows the user to select multiple values. It is only possible if the SIZE attribute is assigned a value greater than 1. On some operating systems, the user may need to hold down certain modifier keys on their keyboard in order to select multiple items.

The <SELECT> tag does not have a value attribute. Each of its possible values must have an <OPTION> tag around it.

You may override the value used by a particular option by specifying a VALUE attribute like this:

<OPTION VALUE="AMEX" >American Express</OPTION>

Options have two optional attributes:

- SELECTED

The SELECTED attribute specifies that the option should be selected by default. When a form is submitted, the name of the <SELECT> tag is submitted along with the value of the selected options.

- VALUE

The VALUE attribute is the value that is passed for the option if it is selected. If this attribute is omitted, then it defaults to the text between the <OPTION> and </OPTION> tags.

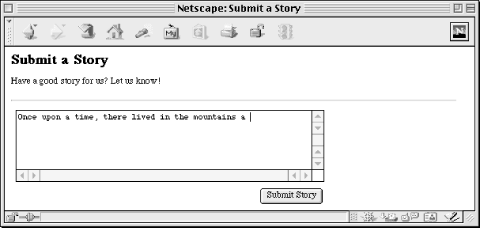

The final form element, the <TEXTAREA> tag, allows users to enter multiple lines of text. See Figure 4.8.

Text areas have an opening and a closing tag:

<TEXTAREA ROWS=10 COLS=40 NAME="comments" WRAP="virtual">Default text</TEXTAREA>

This creates a scrolled text field with a visible area of ten rows and forty columns.

There is no VALUE property for the <TEXTAREA> tag. Default text should be placed between the opening and closing tags. Unlike other HTML tags, white space—including newlines—is not ignored between <TEXTAREA> and </TEXTAREA> tags. A browser will render the example above with “Default” and “text” on separate lines.

Attributes for the <TEXTAREA> tag are:

- COLUMNS

The COLUMNS attribute specifies the width of the text area, but like the size of text fields, browsers size columns differently for variable-width fonts.

- ROWS

The ROWS attribute specifies the number of lines that the text area should display. Text bars have scrollbars to access text that does not fit within the display area.

- WRAP

The WRAP attribute specifies what the browser should do if the user types beyond the right margin, but note that the WRAP attribute is not implemented as uniformly as other tags and attributes. Although most browsers support it, it is actually not included in the HTML 4.0 standard. In general, specifying "virtual” as the WRAP results in the text wrapping within the text area, but it is submitted without newlines. Specifying "physical” as the WRAP also results in the text wrapping for the user, but the line breaks are submitted as part of the text. Users on different operating systems will submit different characters for end-of-line characters. If you specify to omit the WRAP attribute or specify “none” for it, then text will typically scroll beyond the right side of the text area.

In order to access the information contained within the form, we must decode the data that is sent to us. The algorithm for decoding form data is:

Read the query string from

$ENV{QUERY_STRING}.If the

$ENV{REQUEST_METHOD}is POST, determine the size of the request using$ENV{CONTENT_LENGTH}and read that amount of data from the standard input. Append this data to the data read from the query string, if present (this should be joined with "&”).Split the result on the " &” character, which separates name-value pairs (the format is

name=value&name=value...).Split each name-value pair on the “s” character to get the name and value.

Associate each name with its value(s); remember that each option name may have multiple values.

A form sends its parameters as the body of a POST request, or as the query string of a GET request. However, it is possible to create a form that uses the POST method and direct it to a URL containing a query string. Thus, it is possible to get a query string with a POST request.

Here is a first attempt at our subroutine:

sub parse_form_data {

my %form_data;

my $name_value;

my @name_value_pairs = split /&/, $ENV{QUERY_STRING};

if ( $ENV{REQUEST_METHOD} eq 'POST' ) {

my $query = "";

read( STDIN, $query, $ENV{CONTENT_LENGTH} ) == $ENV{CONTENT_LENGTH}

or return undef;

push @name_value_pairs, split /&/, $query;

}

foreach $name_value ( @name_value_pairs ) {

my( $name, $value ) = split /=/, $name_value;

$name =~ tr/+/ /;

$name =~ s/%([\da-f][\da-f])/chr( hex($1) )/egi;

$value = "" unless defined $value;

$value =~ tr/+/ /;

$value =~ s/%([\da-f][\da-f])/chr( hex($1) )/egi;

$form_data{$name} = $value;

}

return %form_data;

}You can use

parse_form_data

like this:

my %query = parse_form_data( ) or error( "Invalid request" );

my $activity = $query{activity};We split the query string into name-value pairs and then store each

pair in @name_value_pairs. Since the client puts

ampersands between key-value pairs, the

split

command specifies an ampersand as the

delimiter. If the request method is POST, then we also read the

content of the request from STDIN. If the number of bytes that we

read does not match the number that we expect, we return

undef. This could happen if the user presses their

browser’s Stop button while sending a request.

We then loop over each of the name-value pairs and spit them into

$name and $value. It is

possible that a parameter can be passed without an equal sign or a

value. This happens for

<ISINDEX> forms, which are

virtually never used anymore, or for

manually

constructed URLs. By setting the $value to an

empty string when it isn’t defined, we avoid warnings from

Perl.

We replace each + with a

space character. We then decode

URL-encoded characters by replacing

strings that start with % and that are followed by

two hexadecimal characters using the expression that we discussed in

Chapter 2. We then add the name and value pair to

our

hash, which we return when we are done.

You may have noticed that there is a problem with our subroutine; it occurs in the hash assignment near the end of the subroutine:

$form_data{$name} = $value;If the form has elements that share the same name, or if there is a scrolling box that supports multiple values, then it is possible for us to receive multiple values for the same name. For example, if you choose “One” and “Two” in a select list with the variable name “numbers,” the query string would look like:

numbers=One&numbers=Two

Our example earlier would save only the last value in the hash. There are a couple different ways we could solve this, but neither is ideal. First, we could convert the value of the hash into an array reference for multiple values by replacing the hash assignment with the following lines:

if ( exists $form_data{$name} ) {

if ( ref $form_data{$name} ) {

push @{ $form_data{$name} }, $value;

}

else {

$form_data{$name} = [ $form_data{$name}, $value ];

}

else {

$form_data{$name} = $value;

}This code is somewhat complex, but because it is hidden in our subroutine, this isn’t really an issue. The real problem with this approach is that CGI scripts using this subroutine need to know which elements can have multiple values and must test each one or run the risk of mistakenly believing the user entered something like “ARRAY(0x19abcde)”, which is Perl’s scalar representation of an array reference. Code to access the values of the “numbers” element would look like this:

my %query = parse_form_data( ) or error( "Invalid request" );

my @numbers = ref( $query{numbers} ) ? @{ $query{numbers} } : $query{numbers};This syntax is awkward. Another approach is to store the multiple

values as a single text string that is delimited by a certain

character, such as a tab or "\0“. This

is easier to code in the subroutine:

if ( exists $form_data{$name} ) {

$form_data{$name} .= "\t$value";

else {

$form_data{$name} = $value;

}It is also easier to read in the CGI script:

my %query = parse_form_data( ) or error( "Invalid request" );

my @numbers = split "\t", $query{numbers};However, there is still a potential for corrupted data if the CGI script is not expecting multiple values.

Fortunately, there is a better solution. Instead of writing an input subroutine ourselves, we can use CGI.pm, which provides an effective solution to this problem along with many other useful features. The next chapter discusses CGI.pm.

Get CGI Programming with Perl, 2nd Edition now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.