One of the hardest challenges for the brain's visual systems is picking out shapes. It's an extraordinarily difficult task. Shapes can not only be moved, rotated, resized, distorted, and obscured, but they can also exist in an endless number of variations.

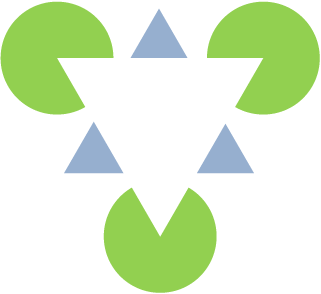

The brain deals with this problem using a toolkit of assumptions. And the brain does a good jobâit can easily beat computerized shape-spotters when scanning pictures, faces, and moving scenes. However, the brain's eagerness to find shapes also leads it to find shapes where there aren't any, as with the white triangle at the forefront of the following picture.

When confronted with this picture, your brain doesn't need to conjure up a white triangle. There's a reasonable alternate explanationâthat the image contains three pacman-like circles with wedges cut out of them, and the wedges are lined up with the gaps between the blue triangles inside. However, a just-so arrangement like this would be unlikely in the natural world, so your brain quickly dismisses that possibility. In essence, your brain picks up on a few clues and performs a rapid analysis to determine the most likely explanation. However, you don't merely think about that most likely explanation, you also see it.

If you rotate the pacmen around, the illusion disappears, and the image reverts to a collection of harmless shapes.

Note

This hints at one of the key limitations of vision. Our brains are tuned to see what's mostly likely in the ordinary, natural world. However, we haven't caught up with the way that manmade products can deliberately hijack these assumptions. In other words, our natural-born visual senses set us up to be the perfect dupes in a world filled with manmade objects.

The brain's obsessive pattern matching isn't limited to shapes. It happens with faces (which we see in unlikely places like house fronts and :) punctuation) and speech sounds (for example, if parts of a word are beeped out in a recording, we "hear" the full word based on what makes sense in the context of a sentence).

The brain is also primed to identify letters and spot words. Can you read this sentence?

If you said "I LIKE IUMRING TQ GQNGIUSIQNS," you have a perverse sense of humor. However, you're also entirely correct.

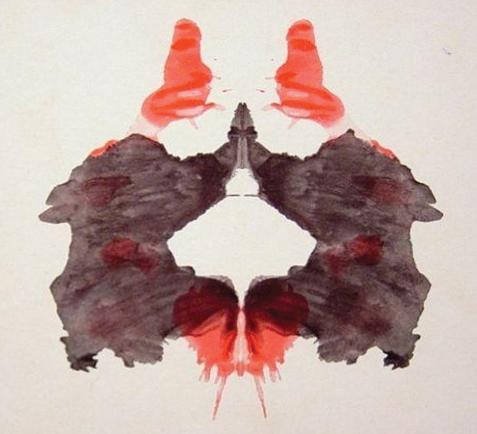

The brain doesn't just organize seemingly unrelated input into patterns; it also has a nasty habit of imagining something into existence. The dubious Rorschach inkblot test is a good example. Take a look at the card shown below:

What do you seeâa masked face, two bears exchanging a high five, or a meaningless splatter of red and black ink?

When looking at an inkblot, most of us are aware of the imaginative power we're investing to transform ambiguous input into a meaningful picture. However, there are many cases where your brain performs the same operation without you realizing the creative leap that it's taking.

Have you ever thought you heard a telephone ringing or a person calling your name while running a noisy appliance like a vacuum? This effect is spurred by the brain's pattern-matching systems, which run wild when hunting through a din of sound. A great illustration of this phenomenon is an experiment that asked volunteers to determine when Bing Crosby's White Christmas began to play in the background of a noisy recording. The devious trick was that there was no White Christmasâonly thirty seconds of white noise. But primed with the expectation of hearing the familiar tune, about a third of the participants reported that they heard it. Incidentally, some people seem to be more susceptible to illusions that draw on imagination like this one. It's thought that they have more creative, fantasy-based minds, which are perfect for free-wheeling brainstorming sessions but not as good at skeptical inquiry.

Tip

The authors of the book Mind Hacks (O'Reilly, 2004) describe the White Christmas illusion, and have provided a noisy recording that you can use to test your friends at www.mindhacks.com/book/48/whitechristmas.mp3.

The white noise study was very small and far from conclusive. Other studies have argued that people who believe in ESP are more likely to find meaningful patterns in random arrangements of dots. In other words:

[Noisy Input with Little Obvious Information] + [Your Brain] = [Things That Go Bump in the Night]

The brain's over-eager pattern-matching system may be a plausible explanation for UFO sightings, ghosts, and other late-night creepies.

Get Your Brain: The Missing Manual now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.