If you've worked with maps, digital or conventional, you'll know that despite my enthusiasm, mapping isn't always easy. Why do we often find it so difficult to make maps of the world around us? How well could you map out the way you normally drive to the supermarket? Usually, it's easier to describe your trip than it is to draw a map. Perhaps we have a perception of what a map must look like and therefore are afraid to draw our own, thinking it might look silly in comparison. Yet some maps drawn by a friend on a napkin might be of more use than any professional city map could ever be.

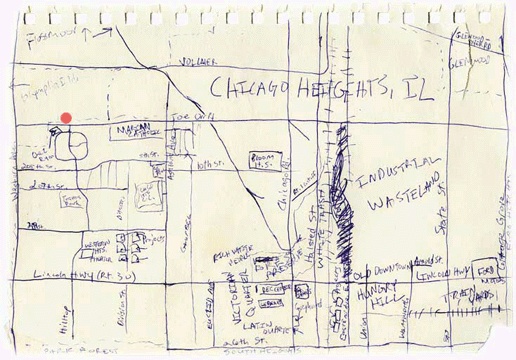

The element of personal knowledge, rather than general knowledge, is what can make a somewhat useful map into one that is very powerful. When words fail to describe the location of something that isn't general knowledge, a map can round out the picture for you. Maps can be used to supplement a verbal description, but because creating a map involves drawing a perspective from your head, it can be very intimidating. That intimidation and lack of ownership over maps has created an interesting dilemma. In our minds, maps are something that professionals create, not the average person. Yet a map like the one shown in Figure 1-1 can have much more meaning to someone than a professional map of the same area. So what are the professional maps lacking? They show mostly common information and often lack personal information that would make the map more useful or interesting to you.

Digital mapping isn't a new topic. Ever since computers could create graphic representations of the earth, people have been creating maps with them. In early computing, people used to draw with ASCII text-based maps. (I remember creating ASCII maps for role-playing games on a Tandy color computer.) However, designing graphics with ASCII symbols wasn't pretty. Thankfully, more sophisticated graphic techniques on personal computers allow you to create your own high-quality maps.

Figure 1-1. A personal map drawn by Ryan Mendenhall showing Chicago Heights, Illinois, U.S.A.; this map is courtesy of Lori Napoleon's maps project web site: http://www.subk.net/maps.html

You might already be creating your own maps but aren't satisfied with the tools. For some, the cost of commercial tools can be prohibitive, especially if you just want to play around for a while to get a feel for the craft. Open source software alleviates the need for immediate, monetary payback on investment.

For others, cost may not be an issue but capabilities are. Just like proprietary software, open source mapping products vary in their features. Improved features might include ease of use or quality of output. One major area of difference is in how products communicate with other products. This is called interoperability and refers to the ability of a program to share data or functions with another program. These often adhere to open standards—protocols for communication between applications. The basic idea is to define standards that aren't dependent on one particular software package; they would depend instead on the communication process a developer decided to implement. An example of these standards in action is the ability of your program to request maps from another mapping program over the Internet. The real power of open standards is evident when your program can communicate with a program developed by a different group/vendor. This is a crucial issue for many large organizations, especially government agencies, where sharing data across departments can make or break the efficiency in that organization. Products that implement open standards will help to ensure the long-term viability of applications you build. Be warned, however, that some products claim to be interoperable yet stop

short of implementing the full standards. Some companies modify the standards for their product, defeating the purpose of those standards. Interoperability standards are also relatively young and in a state of flux.

Costs and capabilities may not be the main barrier for you. Maybe you want to create your own maps but don't know how. Maybe you don't know what tools are available. This book describes some of the free tools available to you, to get you moving toward your end goal of map production.

Another barrier might be that you lack the technical know-how required for digital mapping. While conventional mapping techniques cut out most of the population, digital mapping techniques also prohibit people who aren't very tech-savvy. This is because installing and customizing software is beyond the scope of many computer users. The good news is that those who are comfortable with the customization side of computerized mapping can create easy-to-use tools for others. This provides great freedom for both parties. Those who have mastered the computer skills involved gain by helping fill other's needs. New users gain by being able to view mapping information with minimal effort through an existing mapping application.

Technological barriers exist, but for those who can use a computer and want to do mapping with that computer, the possibilities are endless. The mapping tools described here aren't necessarily easy to use: they require a degree of technical skill. Web mapping programs are more complicated than traditional desktop software. There are often no simple, automated installation procedures, and some custom configuration is required. But in general, once set up, the tools require minimal intervention.

Get Web Mapping Illustrated now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.