In 2002, a group of securities-industry CIOs and IT managers were interviewed about their challenges and strategies with regulatory compliance. Specifically, they were asked about their compliance strategies regarding the usage of instant messaging (IM) technologies, a communication channel that predates the Internet, but exploded in popularity as the Web grew. Because IM allows users to communicate quickly and efficiently with each other in real time for free, it found no shortage of users, or use cases—even in the heavily regulated securities industry.

When the executives were interviewed, however, every single one denied that their organization had any compliance obligations with respect to IM. They were certain of this because they were equally certain that IM was not being used. How were they so sure? “We haven’t issued those technologies, so they’re not being used by our employees,” was the typical response. The reality, however, was an unpleasant surprise to these execs. IM technologies might not have been issued by these companies, but with the technologies freely available and highly useful, their use by company employees was rampant and accelerating.

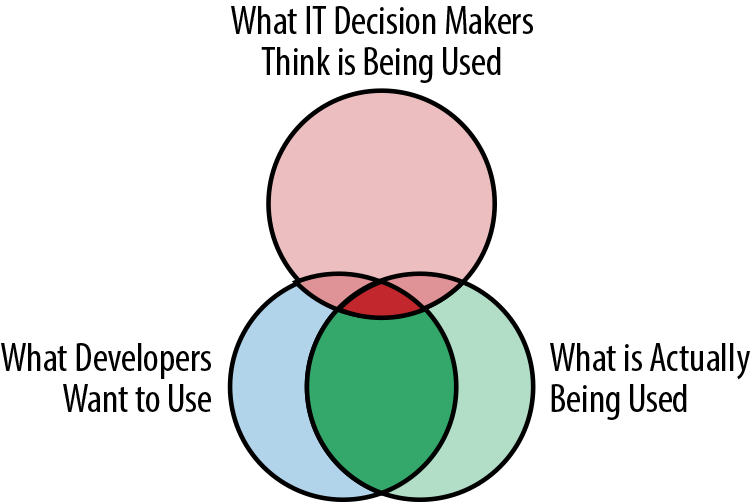

This revelation was to become more and more common over the following decade, however, because the nature of technology adoption was changing. Access to technology has been steadily democratized over the past decade, to the point that, as then CEO of technology provider rPath Billy Marshall put it in 2008, “The CIO is the last to know.” The following Venn diagram depicts the current reality in simple fashion.

This recalibration of the practical authority wielded by IT decision makers has profound ramifications for everyone in or around the technology industry, as well as those businesses that consume technology—which today is virtually every business.

For years, medium-to-large-sized businesses—colloquially referred to as “enterprise buyers”—were the primary consumers of technology, the economic engine that drove technical innovation. Unsurprisingly, the output of the technology industry reflected these buyers’ needs and desires, at the expense of other considerations. Usability was a secondary concern; features like manageability and security were far more important to CIO buyers. Sales and marketing efforts, meanwhile, were crafted around promises of return on investment or labor reduction, rather than personal appeal. There’s a reason the iPhone is an order of magnitude easier to use than the average business software application. Apple needed to convince each customer on the virtues of a given device. Enterprise technology vendors needed to sell only to the one buying the software. If the employees found the products difficult to use, so be it.

In an industry where usage is a function of purchase rather than a real desire for the item, technology providers will obviously optimize for the purchasing process. But in reality, that is no longer true today, and hasn’t been true for years. As with IM or the iPhone, technology is increasingly being driven by bottom-up, rather than top-down, adoption. The world has changed, but only a select few in the technology industry have realized it. As William Gibson might put it, the future is already here, it’s just unevenly distributed.

What does the market think of this new, non-enterprise focused future-present? Currently, Apple is the most valuable technology company in the world, and depending on the price of oil when you read this, the most valuable company in the world, period. As this book goes to press, in fact, Apple is worth more than Adobe, Cisco, Dell, EMC, HP, Oracle, SAP, Red Hat, Sony, and VMware—combined.

In the wake of Apple’s unprecedented success, one obvious question remains: if IT decision makers aren’t making the decisions any longer, who is calling the shots?

The answer is developers. Developers are the most-important constituency in technology. They have the power to make or break businesses, whether by their preferences, their passions, or their own products.

Consider the “rogue” or “shadow” IT departments that are busily metastasizing within organizations large and small all over the planet, simply because they can. These informal, non-sanctioned IT departments handpick, build, and maintain their own technology stacks—technology stacks into which centralized IT has no visibility, and over which it has no control. The result is a world in which Coca Cola or Ford or JP Morgan aren’t the customers any more: their employees are. Vendors are becoming aware that their future relevance and viability will depend not on their salespeoples’ willingness to let the CIO beat them at a round of golf, but their ability to get the rank and file to genuinely value their technologies. As we’ll see, those that manage this transition most successfully turn sales from a costly and complex negotiation to a fait accompli.

This shift is fundamentally reshaping the industry, and has been doing so for more than a few years—yet many in the industry still fail to fully appreciate how profoundly things have changed. That creates an opportunity for those that do to gain a competitive edge. This shift is fundamentally reshaping the industry, but the appreciation for how profoundly things have changed is asymmetrical. That’s surprising, because it has been a decades-long process. But within that asymmetry lies an opportunity.

Geopolitical strategists like Caerus Associates’ David Kilcullen talk about how world leaders today need to evolve from negotiating with governments to negotiating with populations. Thanks to technology, populations are better informed, better connected, and better organized than ever before. The entertainment industry discovered this recently when the Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA) legislation it engineered was defeated by a populist uprising of sorts. As a lobbyist from Ogilvy Government Relations put it, “a well-resourced content group of people completely got outmaneuvered by the guys in the basement.”

The technology industry is no exception. The days when you could simply negotiate with a developer’s boss are over. Today, you need to court developer populations in the same manner that Apple sells phones: individual by individual.

This book is first about helping you understand this shift and its origins, and second about offering suggestions about how to navigate the changed landscape. Developers are now the real decision makers in technology. Learning how to best negotiate with these New Kingmakers, therefore, could mean the difference between success and failure.

Get The New Kingmakers now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.