Chapter 4. Prioritize Where to Start

Now that you have a list of possible models, the next step is to prioritize where to start. Otherwise, it’s easy to fall into the trap of making marginal progress, only to get stuck later.

Incorrect prioritization of risk is one of the top contributors of waste.

What Is Risk?

Before moving on, it helps to define what I mean by risk. We know that startups are highly uncertain, but uncertainty and risk aren’t the same thing. We can be uncertain about a lot of things that aren’t risky.

Douglas Hubbard makes a clear distinction between the two in his book, How to Measure Anything (Wiley):

Uncertainty: The lack of complete certainty, that is, the existence of more than one possibility.

Risk: A state of uncertainty where some of the possibilities involve a loss, catastrophe, or other undesirable outcome.

The good news is that the Lean Canvas automatically captures uncertainties that also are risks—the loss here can be quantified both in terms of opportunity costs and real costs. But not all these risks are equal.

The way you quantify risk in your business model is by quantifying the probabilities of a specific outcome along with quantifying the associated loss if you’re wrong. This is a key step to prioritizing what’s riskiest on your business model and determining where to start.

For instance, in the “How I Iterated This Book” case study from Chapter 2, I didn’t consider pricing for the book as high risk. The reason for this is that even though the loss of nobody buying the book would be huge, the probability of that happening was low provided I wrote a “good” book. That is why I shifted my focus early to testing the “Table of Contents” versus the price.

Risks in a startup can be divided into three general categories, listed here and depicted in Figure 4-1:

- Product risk

Getting the product right

- Customer risk

Building a path to customers

- Market risk

Building a viable business

Tackling all these risks at once can be overwhelming, which is why you need to prioritize them based on the stage of your product, and tackle them systematically.

There is a whole science to quantifying and measuring risks using probabilities and statistical modeling techniques. If you are so inclined, get a copy of Douglas Hubbard’s book, which is a great read even for qualitative measurements like customer interviewing results.

I am not recommending using a statistical model to measure risks on your Lean Canvas, but even a basic understanding of how to ballpark relative risks on your canvas goes a long way toward prioritizing where to start. While what is riskiest in your model will vary depending on the type of product you’re building, I’ve found some initial risks to be universal and a good starting point for ranking business models, which we’ll cover next.

Rank Your Business Models

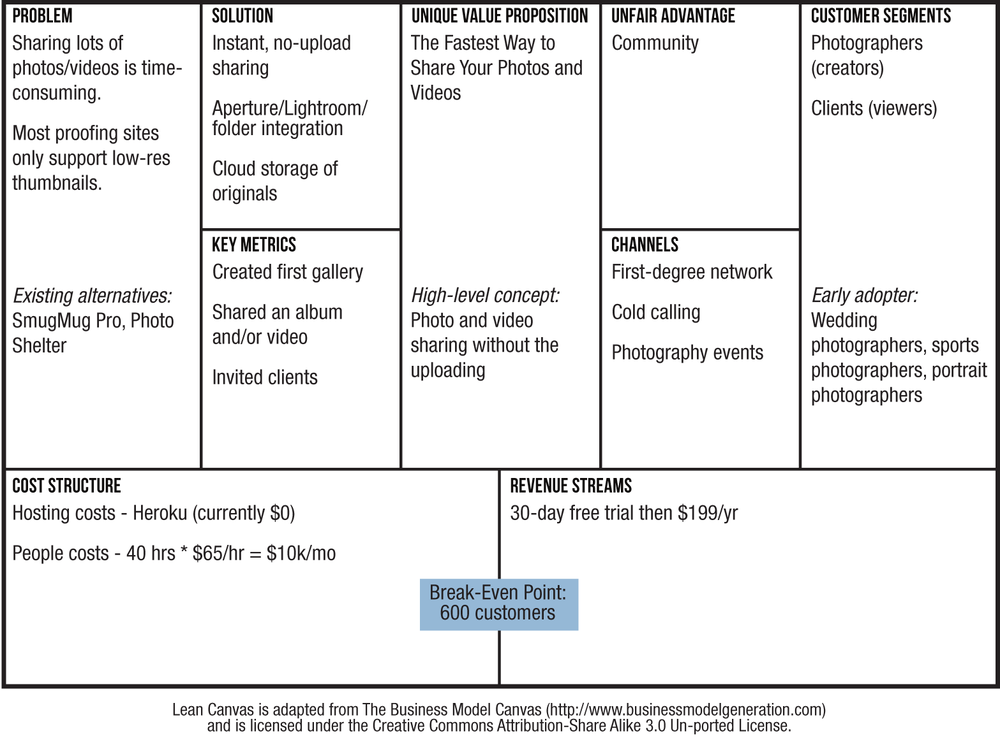

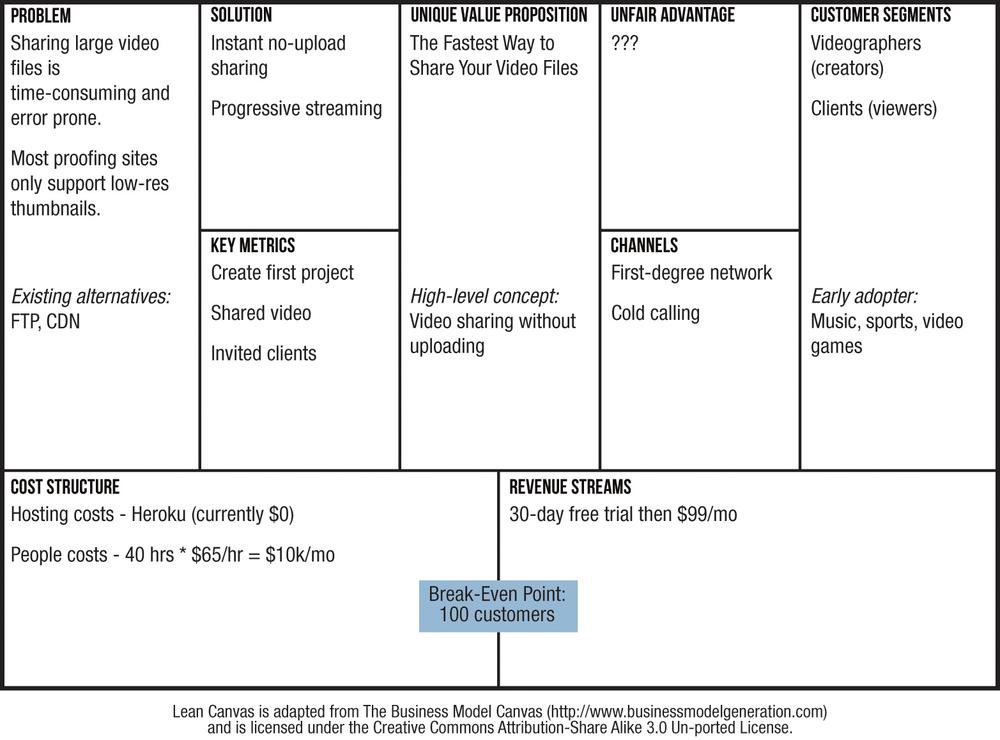

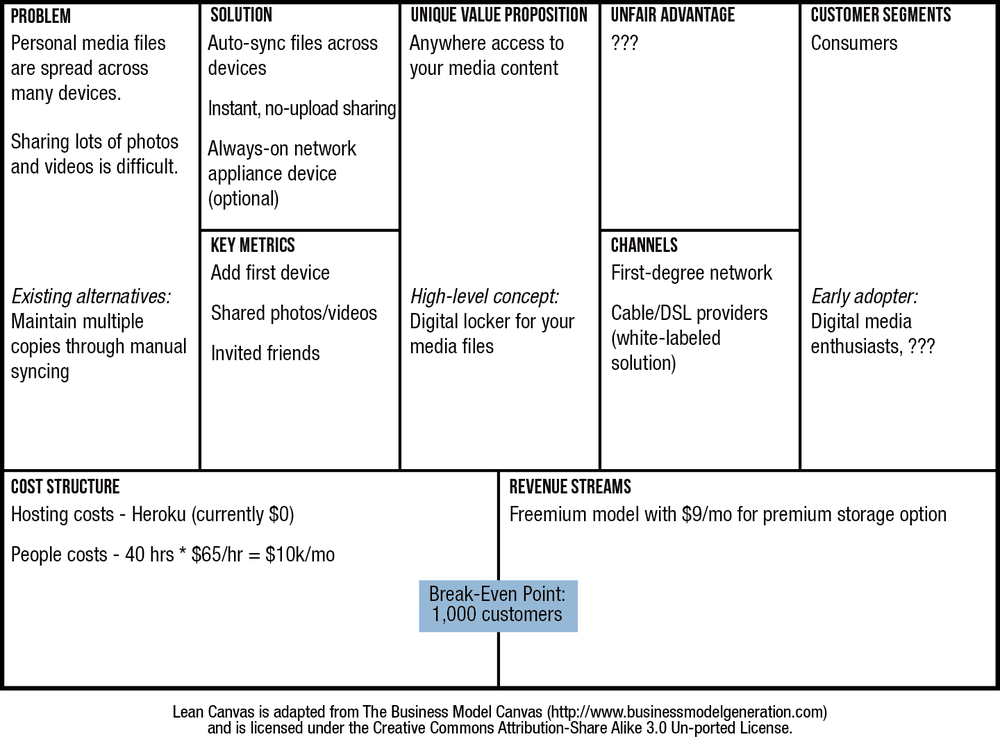

It’s time to lay your Lean Canvases side by side and prioritize which models to start with.

Your objective is to find a model with a big enough market you can reach with customers who need your product that you can build a business around.

Here is the weighting order I use (from highest to lowest):

Customer pain level (Problem)

Prioritize customer segments that you believe will need your product the most. The goal is to have one or more of your top three problems as must-haves for them.

Ease of reach (Channels)

Building a path to customers is one of the harder aspects of building a successful product. If you have an easier path to one segment of customers over others, take that into consideration. It doesn’t guarantee you’ll find a problem worth solving or a viable business model, but it will get you out of the building faster and speed up your learning.

Price/gross margin (Revenue Streams/Cost Structure)

What you can charge for your product is largely driven by the customer segment. Pick a customer segment that allows you to maximize on your margins. The more money you get to keep, the fewer customers you need to reach to break even.

Market size (Customer Segments)

Pick a customer segment that represents a big enough market given the goals for your business.

Technical feasibility (Solution)

Visit your Solution box to ensure that your planned solution not only is feasible, but also represents the minimum feature set to put in front of customers.

Seek External Advice

Another effective technique for further calibrating your risks is getting out of the building and validating them with people other than yourself.[11]

It is imperative that you share your model with at least one other person.

I used to advocate jumping right into customer interviews after documenting my initial models, but now I prefer to first spend a little additional time prioritizing risks and brainstorming alternative models with people other than customers—e.g., advisors.

The main reason I do this is to maximize speed and learning. Customers cannot directly give you all the answers, and due to the iterative and qualitative nature of early learning, validating hypotheses takes time. Furthermore, you might still be targeting too broad a customer segment, too small a customer segment, or the wrong customer segment altogether.

The “right” advisors, on the other hand, can help you identify risks on the “total plan” and help you to further refine and/or outright eliminate some models.

I use the term advisor rather loosely. An early advisor might be a prototypical customer, a potential investor, or another entrepreneur with specific expertise, domain knowledge, or experiential knowledge that applies to you.

For instance, since selling my last company, I’ve shared my lessons learned on CloudFire with several other entrepreneurs who were also looking to target the Parents customer segment. I estimate that my advice and specific tactics have saved them somewhere in the ballpark of three to four months, which is hugely valuable, especially in the earliest stages.

Here are some guidelines for running business model interviews:

- Avoid the 10-slide deck.

I completely avoid a traditional “10-slide deck” because the point of the interview is learning versus pitching. The other extreme, no slides, although most natural, requires practice and may not lead to as many actionable insights because it may be hard for the other person to retain everything you tell her.

My tool of choice is an incremental build of the Lean Canvas delivered on an iPad (or paper). I start with a blank canvas and incrementally reveal parts of the business model as I walk through it.

- Devote 20% of your time to setup, 80% to conversation.

The stacked flow allows me to pace the conversation and leave all the information on the screen. It usually takes me three to five minutes to walk through my model; then I shut up and listen.

I have found that leaving the complete canvas open in front of people always evokes a reaction because people can visualize the entire model and they always have an opinion.

- Ask specific questions.

I specifically want to know:

What do they consider to be the riskiest aspect of this plan?

Have they overcome similar risks? How?

How would they go about testing these risks?

Are there other people I should speak with?

- Be wary of the “advisor paradox.”

As we’ll see shortly, just as customer interviews aren’t about asking customers what they want, these interviews aren’t about asking advisors what to do.

The Advisor Paradox: Hire advisors for good advice but don’t follow it, apply it.

—Venture Hacks

The key is not to take this feedback as either “judgment” or “validation,” but rather as a means of identifying and prioritizing risk.

It is still your job to own your business model. But because you don’t have all the answers, you need to build your startup through a series of conversations—with advisors, customers, investors, and even competitors.

Success is unlocked at the intersection of these conversations, and it’s your job as the entrepreneur to synthesize it into a coherent whole.

- Recruit visionary advisors.

Much like early adopters want to help when you nail their problems, visionary advisors will want to help when you present them with interesting problems that trigger their strengths and passion.

You’ll know if there’s a fit based on their answers and body language. If so, consider bringing them on as formal advisors.

[11] This is a technique that Douglas Hubbard describes as the “Instinctive Bayesian Approach” in his book.

Get Running Lean, 2nd Edition now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.