When you implement

mod_perl on your system,

it’s very important to go through the default

configuration file (httpd.conf), because most of

the default settings were designed without mod_perl in mind. Some

variables (such as MaxClients) should be adapted

to the capabilities of your system, while some (such as

KeepAlive, in many cases) should be disabled,

because although they can improve performance for a plain Apache

server, they can reduce performance for a mod_perl server.

Correct configuration of the MinSpareServers,

MaxSpareServers, StartServers,

MaxClients, and

MaxRequestsPerChild parameters is very important.

If they are too low, you will under-use the system’s

capabilities. If they are too high, it is likely that the server will

bring the machine to its knees.

The KeepAlive directive improves the performance

of a plain Apache server by saving the TCP handshake if the client

requests more than one object from your server. But you

don’t want this option to be enabled under mod_perl,

since it will keep a large mod_perl process tied to the client and do

nothing while waiting for the timeout to occur.

We will talk about these and other issues in the following sections.

It’s important to

specify

MaxClients on the basis of the resources

your machine has. The MaxClients directive sets

the limit on the number of simultaneous

requests that can be supported. No

more than this number of child server processes will be created. To

configure more than 256 clients, you must edit the

HARD_SERVER_LIMIT entry in

httpd.h and recompile Apache.

With a plain Apache server, it doesn’t matter

much if you run many child

processes—the processes are about 1 MB each (most of it

shared), so they don’t eat a lot of RAM. The

situation is different with mod_perl, where the processes can easily

grow to 10 MB and more. For example, if you have

MaxClients set to 50, the memory usage becomes 50

× 10 MB = 500 MB.[1] Do you have 500 MB of RAM

dedicated to the mod_perl server?

With a high MaxClients, if you get a high load the

server will try to serve all requests immediately. Your CPU will have

a hard time keeping up, and if the child size multiplied by the

number of running children is larger than the total available RAM,

your server will start swapping. The swapping will slow down

everything, which will lead to more swapping, slowing down everything

even more, until eventually the machine will die.

It’s important that you take pains to ensure that

swapping does not normally happen. Swap space is an emergency pool,

not a resource to be used routinely. If you are low on memory and you

badly need it, buy it. Memory is cheap.

We want the value of MaxClients to be as small as

possible, because in this way we can limit the resources used by the

server’s children. Since we can restrict each

child’s process size, as discussed later, the

calculation of MaxClients is straightforward:

So if we have 400 MB for the mod_perl server to use, we can set

MaxClients to 40 if we know that each child is

limited to 10 MB of memory.

You may be wondering what will happen to your server if there are

more concurrent users than MaxClients. This

situation is pointed out by the following warning message in the

error_log

file:

[Sat May 18 13:40:35 2002] [error] server reached MaxClients setting, consider raising the MaxClients setting

Technically there is no problem—any connection attempts over

the MaxClients limit will normally be queued, up

to a number based on the ListenBacklog directive.

When a child process is freed at the end of a different request, the

next waiting connection will be served.

But it is an error, because clients are being put in the queue rather than getting served immediately, despite the fact that they do not get an error response. The error can be allowed to persist to balance available system resources and response time, but sooner or later you will need to get more RAM so you can start more child processes. The best approach is to prevent this situation from arising in the first place, and if it keeps on happening you should start worrying about it.

In Chapter 10 we showed that when memory sharing is available, the approximate real memory used can be calculated by adding up all the unshared memory of the client processes plus the memory of the parent process, or, if the latter is unknown, the maximum shared memory size of a single child process, which is smaller than the memory size of the parent process but good enough for our calculations. We have also devised the following formula:

where Total_RAM is of course the estimated total

RAM available to the web server.

Let’s perform some calculations, first with sharing in place:

Total_RAM = 500Mb Max_Process_Size = 10Mb Min_Shared_RAM_per_Child = 4Mb

then with no sharing in place:

With sharing in place, if your numbers are similar to the ones in our example, you can have 64% more servers without buying more RAM (82 compared to 50).

If you improve sharing and the sharing level is maintained throughout the child’s life, you might get:

Total_RAM = 500Mb Max_Process_Size = 10Mb Shared_RAM_per_Child = 8Mb

Here we have 392% more servers (246 compared to 50)!

There is one more nuance to remember. The number of requests per

second that your server can serve won’t grow

linearly when you raise the value of MaxClients.

Assuming that you have a lot of RAM available and you try to set

MaxClients as high as possible, you will find that

you eventually reach a point where increasing the

MaxClients value will not improve performance.

The more clients that are running, the more CPU time will be required and the fewer CPU time slices each process will receive. The response latency (the time to respond to a request) will grow, so you won’t see the expected improvement. Let’s explore these issues.

The test handler that we have used is shown in Example 11-1. You can see that it does mostly CPU-intensive computations.

Example 11-1. Book/HandlerBenchmark.pm

package Book::HandlerBenchmark;

use Apache::Constants qw(:common);

sub handler {

$r = shift;

$r->send_http_header('text/html');

$r->print("Hello");

my $x = 100;

my $y = log ($x ** 100) for (0..100);

return OK;

}

1;Here’s the configuration section to enable this handler:

PerlModule Book::HandlerBenchmark

<Location /benchmark_handler_middle>

SetHandler perl-script

PerlHandler Book::HandlerBenchmark

</Location>Now we will run the benchmark for different values of

MaxClients. The results are:

MaxClients | avtime completed failed rps

--------------------------------------------

100 | 333 50000 0 755

125 | 340 50000 0 780

150 | 342 50000 0 791

175 | 338 50000 0 783

200 | 339 50000 0 785

225 | 365 50000 0 760

250 | 402 50000 0 741

---------------------------------------------

Non-varying sub-test parameters:

---------------------------------------------

MaxRequestsPerChild : 0

StartServers : 100

Concurrency : 300

Number of requests : 50000

---------------------------------------------

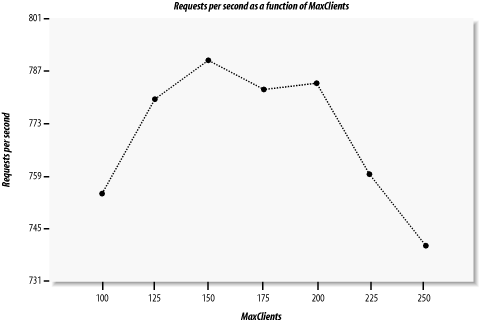

Figure 11-1 depicts requests per second versus

MaxClients. Looking at this figure, you can see

that with a concurrency level of 300, the performance is almost

identical for MaxClients values of 150 and 200,

but it goes down for the value of 100 (not enough processes) and are

even worse for the value of 250 (too many processes competing over

CPU cycles). Note that we have kept the server fully loaded, since

the number of concurrent requests was always higher than the number

of available processes, which means that some requests were queued

rather than responded to immediately. When the number of processes

went above 200, more and more time was spent by the processes in the

sleep state and context switching, enlarging the latency of response

generation. On the other hand, with only 100 available processes, the

CPU was not fully loaded and we had plenty of memory available. You

can see that in our case, a MaxClients value of

150 is close to optimal.[2]

This leads us to an interesting discovery, which we can summarize in the following way: increasing your RAM might not improve the performance if your CPU is already fully loaded with the current number of processes. In fact, if you start more processes, you will get a degradation in performance. On the other hand, if you decide to upgrade your machine with a very powerful CPU but you don’t add enough memory, the machine will use swap memory or the CPU will be under-used; in any case, the performance will be poor. Whenever you opt for a more powerful CPU, you must always budget for enough extra memory to ensure that the CPU’s greater processing power is fully utilized. It is generally best to add more memory in the first place to see if that helps with performance problems (assuming you follow our tuning advice as well).

To discover the right configuration for your server, you should run benchmarks on a machine with identical hardware to the one that you are going to use in production. Try to simulate the probable loads your machine will experience. Remember that the load will be variable, and plan accordingly. Experiment with the configuration parameters under different loads to discover the optimal balance of CPU and RAM use for your machine. When you change the processor or add RAM, retest the configuration to see how to change the settings to get the best from the new hardware.

You can tune your machine using reports like the one in our example,

by analyzing either the requests per second

(rps) column, which shows the throughput of your

server, or the average processing time (avtime)

column, which can be seen as the latency of your server. Take more

samples to build nicer linear graphs, and pick the value of

MaxClients where the curve reaches a maximum value

for a throughput graph or reaches the minimum value for a latency

graph.

The MaxRequestsPerChild

directive sets the limit on the

number of requests that an individual child process can handle during

its lifetime. After MaxRequestsPerChild requests,

the child process will die. If MaxRequestsPerChild

is zero, the process will live until the server kills it (because it

is no longer needed, which will depend on the value of

MinSpareServers and the number of current

requests) or until the server itself is stopped.

Setting MaxRequestsPerChild to a non-zero limit

solves some memory-leakage problems caused by sloppy programming

practices and bugs, whereby a child process consumes a little more

memory after each request. In such cases, and where the directive is

left unbounded, after a certain number of requests the children will

use up all the available memory and the server will die from memory

starvation. Note that sometimes standard system libraries leak memory

too, especially on operating systems with bad memory management.

If this is your situation you may want to set

MaxRequestsPerChild to a small number. This will

allow the system to reclaim the memory that a greedy child process

has consumed when it exits after

MaxRequestsPerChild requests.

But beware—if you set this number too low, you will lose some

of the speed bonus you get from mod_perl. Consider using

Apache::PerlRun if the leakage is in the CGI

script that you run. This handler flushes all the memory used by the

script after each request. It does, however, reduce performance,

since the script’s code will be loaded and

recompiled for each request, so you may want to compare the loss in

performance caused by Apache::PerlRun with the

loss caused by memory leaks and accept the lesser of the evils.

Another approach is to use the memory usage-limiting modules,

Apache::SizeLimit or

Apache::GTopLimit. If you use either of these

modules, you shouldn’t need to set

MaxRequestPerChild (i.e., you can set it to

0), although for some developers, using both in

combination does the job. These modules also allow you to control the

maximum unshared and minimum shared memory sizes. We discuss these

modules in Chapter 14.

With mod_perl

enabled, it might take as

much as 20 seconds from the time you start the server until it is

ready to serve incoming requests. This delay depends on the OS, the

number of preloaded modules, and the process load of the machine.

It’s best to set StartServers and

MinSpareServers to high numbers, so that if you

get a high load just after the server has been restarted, the fresh

servers will be ready to serve requests immediately.

To maximize the benefits of mod_perl, you don’t want

to kill servers when they are idle; rather, you want them to stay up

and available to handle new requests immediately. We think an ideal

configuration is to set MinSpareServers and

MaxSpareServers to similar (or even the same)

values. Having MaxSpareServers close to

MaxClients will completely use all of your

resources (if MaxClients has been chosen to take

full advantage of the resources) and make sure that at any given

moment your system will be capable of responding to requests with the

maximum speed (assuming that the number of concurrent requests is not

higher than MaxClients—otherwise, some

requests will be put on hold).

If you keep a small number of servers active most of the time, keep

StartServers low. Keep it low especially if

MaxSpareServers is also low, as if there is no

load Apache will kill its children before they have been utilized at

all. If your service is heavily loaded, make

StartServers close to

MaxClients, and keep

MaxSpareServers equal to

MaxClients.

If your server performs other work besides running the

mod_perl-enabled server—for example, an SQL server—make

MinSpareServers low so the memory of unused

children will be freed when the load is light. If your

server’s load varies (i.e., you get loads in bursts)

and you want fast responses for all clients at any time, you will

want to make it high, so that new children will be respawned in

advance and able to handle bursts of requests.

For MaxSpareServers, the logic is the same as for

MinSpareServers—low if you need the machine

for other tasks, high if it’s a host dedicated to

mod_perl servers and you want a minimal delay between the request and

the response.

If your mod_perl server’s httpd.conf file includes the following directives:

KeepAlive On MaxKeepAliveRequests 100 KeepAliveTimeout 15

you have a real performance penalty, since after completing the

processing for each request, the process will wait for

KeepAliveTimeout seconds before closing the

connection and will therefore not be serving other requests during

this time. With this configuration you will need many more concurrent

processes on a server with high traffic.

If you use the mod_status or Apache::VMonitor

server status reporting tools, you will see a process in

K state when it’s in

KeepAlive state.

You will probably want to switch this feature off:

KeepAlive Off

The other two directives don’t matter if

KeepAlive is Off.

However, you might consider enabling KeepAlive if

the client’s browser needs to request more than one

object from your mod_perl server for a single HTML page. If this is

the situation, by setting KeepAlive

On, for every object rendered in the HTML page on

the client’s browser you save the HTTP connection

overhead for all requests but the first one.

For example, if the only thing your mod_perl server does is process

ads, and each of your pages has 10 or more banner ads (which is not

uncommon today), your server will work more efficiently if a single

process serves them all during a single connection. However, your

client will see a slightly slower response, since the banners will be

brought one at a time and not concurrently, as is the case if each

<img> tag opens a separate connection.

SSL connections benefit the most from KeepAlive if

you don’t configure the server to cache session IDs.

See the mod_ssl documentation for how to do this.

You have probably followed our advice to send all the requests for

static objects to a plain Apache (proxy/accelerator) server. Since

most pages include more than one unique static image, you should keep

the default KeepAlive setting of the non-mod_perl

server (i.e., keep it On). It will probably also

be a good idea to reduce the KeepAliveTimeout to 1

or 2 seconds—a client is going to send a new request on the

KeepAlive connection immediately, and the first

bits of the request should reach the server within this limit, so

wait only for the maximum latency of a modem connection plus a little

bit more.

Another option is for the proxy/accelerator to keep the connection open to the client but make individual connections to the server, read the responses, buffer them for sending to the client, and close the server connection. Obviously, you would make new connections to the server as required by the client’s requests.

By default,

PerlSetupEnv

is

On, but PerlSetupEnv Off is

another optimization you should consider.

mod_perl modifies the environment to make it appear as if the script

were being called under the CGI protocol. For example, the

$ENV{QUERY_STRING} environment variable is

initialized with the contents of $r->args( ),

and the value returned by $r->server_hostname(

) is put into $ENV{SERVER_NAME}.

But populating %ENV is expensive. Those who have

moved to the mod_perl API no longer need this duplicated data and can

improve performance by turning it off. Scripts using the

CGI.pm module require PerlSetupEnv

On because that module relies on the environment created by

mod_cgi. This is yet another reason why we recommend using the

Apache::Request module in preference to

CGI.pm.

Note that you can still set environment variables when

PerlSetupEnv is Off. For

example, say you use the following configuration:

PerlSetupEnv Off

PerlModule Apache::RegistryNG

<Location /perl>

PerlSetEnv TEST hi

SetHandler perl-script

PerlHandler Apache::RegistryNG

Options +ExecCGI

</Location>Now issue a request for the script shown in Example 11-2.

Example 11-2. setupenvoff.pl

use Data::Dumper;

my $r = Apache->request( );

$r->send_http_header('text/plain');

print Dumper \%ENV;You should see something like this:

$VAR1 = {

'GATEWAY_INTERFACE' => 'CGI-Perl/1.1',

'MOD_PERL' => 'mod_perl/1.26',

'PATH' => '/bin:/usr/bin:/usr... snipped ...',

'TEST' => 'hi'

};Note that we got the value of the TEST environment

variable we set in httpd.conf.

If (using

truss,

strace, or another tool available for your OS)

you watch the system calls that your mod_perl server makes while

processing a request, you will notice that a few stat(

) calls are made, and these are quite expensive. For

example, if you have your DocumentRoot set to

/home/httpd/docs and you fetch

http://localhost/perl-status, you will see:

[snip]

stat("/home/httpd/docs/perl-status", 0xbffff8cc) = -1

ENOENT (No such file or directory)

stat("/home/httpd/docs", {st_mode=S_IFDIR|0755,

st_size=1024, ...}) = 0

[snip]If you have some dynamic content and your virtual relative URI is

looks like /news/perl/mod_perl/summary (i.e.,

there is no such directory on the web server—the path

components are used only for requesting a specific report), this will

generate five stat( ) calls before the

DocumentRoot is reached and the search is stopped.

You will see something like this:

stat("/home/httpd/docs/news/perl/mod_perl/summary", 0xbffff744) = -1

ENOENT (No such file or directory)

stat("/home/httpd/docs/news/perl/mod_perl", 0xbffff744) = -1

ENOENT (No such file or directory)

stat("/home/httpd/docs/news/perl", 0xbffff744) = -1

ENOENT (No such file or directory)

stat("/home/httpd/docs/news", 0xbffff744) = -1

ENOENT (No such file or directory)

stat("/home/httpd/docs",

{st_mode=S_IFDIR|0755, st_size=1024, ...}) = 0How expensive are these calls? Let’s use the

Time::HiRes

module to find out.

The script in Example 11-3, which you should run on

the command line, takes a time sample at the beginning, then does a

million stat( ) calls to a nonexistent file,

samples the time at the end, and prints the average time it took to

make a single stat( ) call.

Example 11-3. stat_call_sample.pl

use Time::HiRes qw(gettimeofday tv_interval); my $calls = 1_000_000; my $start_time = [ gettimeofday ]; stat "/foo" for 1..$calls; my $end_time = [ gettimeofday ]; my $avg = tv_interval($start_time,$end_time) / $calls; print "The average execution time: $avg seconds\n";

Before we actually run the script we should distinguish between two different scenarios. When the server is idle, the time between the first and the last system call will be much shorter than the same time measured on a loaded system. This is because on an idle system, a process can use the CPU very often, whereas on a loaded system, lots of processes compete for CPU time and each process has to wait longer to get the same amount of CPU time.

So first we run the above code on an unloaded system:

panic% perl stat_call_sample.pl The average execution time: 4.209645e-06 seconds

Here it takes about four microseconds to execute a stat(

) call. Now we’ll start a CPU-intensive

process in one console (make sure to kill the process afterward!).

The following code keeps the CPU busy all the time:

panic% perl -e '1 while 1'

And now we run the stat_call_sample.pl script in another console:

panic% perl stat_call_sample.pl The average execution time: 8.777301e-06 seconds

You can see that the average time has doubled (about eight microseconds). This is intuitive, since there were two processes competing for CPU resources. Now if we run four occurrences of the above code:

panic% perl -e '1**1 while 1' & panic% perl -e '1**1 while 1' & panic% perl -e '1**1 while 1' & panic% perl -e '1**1 while 1' &

and run our script in parallel with these processes, we get:

panic% perl stat_call_sample.pl 2.0853558e-05 seconds

So the average stat( ) system call is five times

longer now (about 20 microseconds). Now if you have 50 mod_perl

processes that keep the CPU busy all the time, the stat(

) call will be 50 times slower and it’ll

take 0.2 milliseconds to complete a series of calls. If you have five

redundant calls, as in the strace example above,

they add up to one millisecond. If you have more processes constantly

consuming CPU resources, this time adds up. Now multiply this time by

the number of processes that you have and you get a few seconds lost.

For some services this loss is insignificant, while for others it

could be very significant.

So why does Apache do all these redundant stat( )

calls? The reason is the default installed

TransHandler. One solution would be to supply our

own, which would be smart enough not to look for this virtual path

and would immediately return OK. In cases where

you have a virtual host that serves only dynamically generated

documents, you can override the default

PerlTransHandler

with the following one:

PerlModule Apache::Constants

<VirtualHost 10.10.10.10:80>

...

PerlTransHandler Apache::Constants::OK

...

</VirtualHost>The Apache::Constants::OK constant (which is

actually a subroutine) is used here as a handler that does nothing

but finish the translation phase by returning OK.

By skipping the default translation handler, which tries to find a

filesystem component that matches the given URI, you save the

redundant stat( ) calls!

As you see, it affects only this specific virtual host. Remember that

PerlTransHandler cannot appear inside a specific

<Location> or similar section, because the

request has not yet been associated with a particular file or

directory.

As we will show next, Apache’s default

TransHandler may perform several stat(

) calls when the request is served by a virtual resource

that doesn’t reside on the filesystem. Things get

worse when Apache is configured to look for

.htaccess files, adding many redundant

open( ) calls.

Let’s start with the following simple configuration and try to reduce the number of redundant system calls to a minimum:

DocumentRoot "/home/httpd/docs"

<Directory />

AllowOverride All

</Directory>

<Location /foo/test>

SetHandler perl-script

PerlHandler Apache::Foo

</Location>The above configuration causes the Perl handler( )

defined in Apache::Foo to be executed when we make

a request to /foo/test. Notice that in the test

setup there is no real file to be executed and no

.htaccess file.

Using the above configuration, the system calls trace may look as follows:

stat("/home/httpd/docs/foo/test", 0xbffff8fc) = -1 ENOENT

(No such file or directory)

stat("/home/httpd/docs/foo", 0xbffff8fc) = -1 ENOENT

(No such file or directory)

stat("/home/httpd/docs",

{st_mode=S_IFDIR|0755, st_size=1024, ...}) = 0

open("/.htaccess", O_RDONLY) = -1 ENOENT

(No such file or directory)

open("/home/.htaccess", O_RDONLY) = -1 ENOENT

(No such file or directory)

open("/home/httpd/.htaccess", O_RDONLY) = -1 ENOENT

(No such file or directory)

open("/home/httpd/docs/.htaccess", O_RDONLY) = -1 ENOENT

(No such file or directory)

stat("/home/httpd/docs/test", 0xbffff774) = -1 ENOENT

(No such file or directory)

stat("/home/httpd/docs",

{st_mode=S_IFDIR|0755, st_size=1024, ...}) = 0Now we modify the <Directory> entry and add

AllowOverride None, which, among other things,

tells Apache not to search for .htaccess files:

<Directory />

AllowOverride None

</Directory>After restarting the server and issuing a request to

/foo/test, we see that the four open(

) calls for .htaccess have gone. The

remaining system calls are:

stat("/home/httpd/docs/foo/test", 0xbffff8fc) = -1 ENOENT

(No such file or directory)

stat("/home/httpd/docs/foo", 0xbffff8fc) = -1 ENOENT

(No such file or directory)

stat("/home/httpd/docs",

{st_mode=S_IFDIR|0755, st_size=1024, ...}) = 0

stat("/home/httpd/docs/test", 0xbffff774) = -1 ENOENT

(No such file or directory)

stat("/home/httpd/docs",

{st_mode=S_IFDIR|0755, st_size=1024, ...}) = 0Next, let’s try to shortcut the foo location with:

Alias /foo/ /

which makes Apache look for the file in the / directory and not under /home/httpd/docs/foo. Let’s restart the server and try again:

stat("/test", 0xbffff8fc) = -1 ENOENT (No such file or directory)Now we’ve got only one stat( )

call left!

Let’s replace the Alias setting

we have just added with:

PerlModule Apache::Constants PerlTransHandler Apache::Constants::OK

as explained earlier. When we issue the request, we see no remaining

stat( ) calls. This technique works if you serve

content using only mod_perl handlers, since CGI scripts and other

files won’t be looked for on the filesystem now.

Also, since the default translation handler is now skipped,

$r->filename now won’t be set.

If you want to serve both mod_perl handlers and real files, you will

have to write your own

PerlTransHandler

to handle requests as desired. For

example, the following PerlTransHandler will not

look up the file on the filesystem if the URI starts with

/foo—the handler will return

DECLINED and the default

PerlTransHandler will be used:

PerlTransHandler 'sub { return shift->uri( ) =~ m|^/foo| \

? Apache::Constants::OK \

: Apache::Constants::DECLINED; }'Let’s see the same configuration using a

<Perl> section and a dedicated package (see

Example 11-4).

Example 11-4. perl_section.conf

<Perl>

package Book::Trans;

use Apache::Constants qw(:common);

sub handler {

my $r = shift;

return OK if $r->uri( ) =~ m|^/foo|;

return DECLINED;

}

package Apache::ReadConfig;

$PerlTransHandler = "Book::Trans";

</Perl>Here we have defined the Book::Trans package and

implemented the handler( ) function. Then we have

assigned this handler to the PerlTransHandler.

You can move the code in the module into an external file (e.g.,

Book/Trans.pm) and configure the

PerlTransHandler with:

PerlTransHandler Book::Trans

in the normal way (no <Perl> section

required).

Now we’ll run some benchmarks to test the solutions

described above, both individually and in groups. To make the

difference in the number of stat( ) calls more

prominent, we will use a very light handler that just prints

something out.

The module that we have used is shown in Example 11-5.

Example 11-5. Book/News.pm

package Book::News;

use Apache::Constants qw(:common);

sub handler {

my $r = shift;

my $uri = $r->uri;

my @sections = split "/", $uri;

# in a real handler you'd do some DB lookup and return the story:

# my $story = get_story(@sections);

$r->send_http_header('text/plain');

print "Story matching @sections\n";

return OK;

}

1;This is the URI we have used for testing:

/news/perl/mod_perl/summary

Notice that the URI is long enough to generate many stat(

) calls with the default Apache configuration.

This is the main configuration:

<Location /news>

SetHandler perl-script

PerlHandler +Book::News

</Location>Now we try different configurations and see how they influence performance. Each configuration is listed with a tag in parentheses that is used as a key in the table and explanation that follows.

(default) Nothing was added:

<Directory /> AllowOverride All </Directory>(noht) Prevent .htaccess lookup:

<Directory /> AllowOverride None </Directory>(alias) Location alias shortcutting:

Alias /news /

(trans) Using a nondefault

TransHandler:<Perl> package Book::Trans; use Apache::Constants qw(:common); sub handler { my $r = shift; return OK if $r->uri( ) =~ m|^/news|; return DECLINED; } package Apache::ReadConfig; $PerlTransHandler = "Book::Trans"; </Perl>

The results, sorted by the requests per second (rps) rate, are:

Options | avtime completed failed rps -----------|------------------------------- noht+alias | 27 5000 0 996 noht+trans | 29 5000 0 988 trans | 29 5000 0 975 alias | 28 5000 0 974 noht | 32 5000 0 885 default | 34 5000 0 827

with static arguments:

Concurrency : 30 Number of requests : 5000

The concurrency and connections don’t matter here; we are concerned with the relative rather than the absolute numbers.

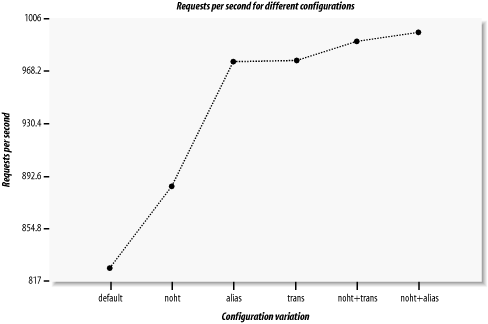

Figure 11-2 depicts these results.

Preventing .htaccess lookup

(noht) improved the performance by about 8% (885

versus 827). Using alias shortcutting (alias) or

a nondefault TransHandler

(trans) gave even more of a performance boost:

since for a long URI like the one in our example, each directory

generates a few stat( ) and open(

) system calls, the speedup was around 15% compared to the

standard configuration (default). Grouping the

prevention of .htaccess lookup

(noht) plus one of the techniques that

don’t look for the nonexistent file in the

filesystem (alias or trans)

gave a performance boost of about 18% (996 versus 827).

As we have seen, the number of pseudo-subdirectories is in direct

proportion to the number of stat( ) and

open( ) system calls that are made. To prove this,

let’s use the standard configuration

(default) and benchmark three URIs with a

different number of sections (directories), without counting the

first section (/news):

Sections URI --------------------------------------------- 1 /news/perl 3 /news/perl/mod_perl/summary 5 /news/perl/mod_perl/summary/foo/bar

The results are what we expected:

Sections | avtime completed failed rps

---------------------------------------------------

1 | 33 5000 0 849

3 | 34 5000 0 829

5 | 35 5000 0 801

---------------------------------------------------Each of the two sections add an extra millisecond to the average processing and connection time, which reduces performance by about 25 requests per second.

It’s important to read the figures cautiously. Improving performance by 20% simply by adding a few configuration directives is not likely to be achieved in practice. In our test code we used a very light handler, which did nothing but send a few lines of text without doing any processing. When you use real code, whose runtime is not 30-40 milliseconds but 300-400 milliseconds, the improvement of 7 milliseconds on average (as we saw between the standard configuration (default), giving 34 ms, and the combination of noht and alias, giving 27 ms) might be insignificant. The tuning we’ve discussed here is important mostly for servers that serve millions of requests per day and where every millisecond counts.

But even if your server has a light load, you can still make it a little bit faster. Use a benchmark on the real code and see whether you win something or not.

The two options

FollowSymLinks

and

SymLinksIfOwnerMatch

are designed for the user’s security. Unless

FollowSymLinks is enabled, symbolic links will not

be followed by the server. If SymLinksIfOwnerMatch

is enabled, the server will follow symbolic links only when the

target file or directory is owned by the same user as the link. Note

that the two options are ignored if set within a

<Location> block.

This protection costs a little overhead for each request. Wherever in your URL-space you do not have this setting:

Options FollowSymLinks

or you do have this setting:

Options SymLinksIfOwnerMatch

Apache will have to issue an extra call to lstat(

) per directory segment in the path to the file. For

example, if you have:

DocumentRoot /home/httpd/docs

<Directory />

Options SymLinksIfOwnerMatch

</Directory>and a request is made for the URI /index.html,

Apache will perform lstat( ) on these three

directories and one file:

/home /home/httpd /home/httpd/docs /home/httpd/docs/index.html

The deeper the file is located in the filesystem, the more

lstat( ) system calls will be made. The results of

these lstat( ) calls are never cached, so they

will occur for every single request. If you really want the

symbolic-links security checking, you can do something like this:

DocumentRoot /home/httpd/docs

<Directory />

Options FollowSymLinks

</Directory>

<Directory /home/httpd/docs>

Options -FollowSymLinks +SymLinksIfOwnerMatch

</Directory>This at least avoids the extra checks for the

DocumentRoot path. Note that

you’ll need to add similar sections if you have any

Alias or RewriteRule paths

outside of your document root. For highest performance, and no

symbolic link protection, set the FollowSymLinks

option everywhere, and never set the

SymLinksIfOwnerMatch option.

You should make sure that your httpd.conf file has this setting:

HostnameLookups Off

This is the default.

If this directive is set to On (or even worse,

Double), Apache will try to use DNS resolution to

translate the client’s IP address into its hostname

for every single request.

The problem is that there are many servers with broken reverse DNS, which means that resolution will never succeed, but it might take a significant time for the lookup attempt to time out. The web page will not be served before the lookup has either succeeded or timed out, because it’s assumed that if you have this feature enabled you want to know the hostname from which the request came. Consequently Apache won’t run any script or handler until the lookup attempt has concluded.

Moreover, you can end up with a hostname that is completely useless and gives you far less information than the IP address would. To avoid this problem you can enable:

HostnameLookups Double

which does a reverse lookup, then a forward lookup on what it gets to make sure that the IP address is not being spoofed. However, this double lookup makes it even slower.

If you need DNS names in some CGI script or handler, you should use

gethostbyname( ) or its equivalents.

In addition to having HostnameLookups turned off,

you should avoid using hostname-based access control and use IP-based

access control instead. If you have a setting like this:

<Location /perl-status>

...

Order deny, allow

Deny from all

Allow from www.example.com

</Location>the server will have to perform a double reverse DNS lookup for each

incoming IP address to make sure it matches the domain name listed in

the Allow directive and is not being spoofed. Of

course, in our example this will happen only for requests for URIs

starting with /perl-status.

This is another way to do the authorization based on the IP address:

<Location /perl-status>

...

Order deny, allow

Deny from all

Allow from 128.9.176.32

</Location>Note that since some IP addresses map to multiple hosts (multiple CNAME records), this solution will not always do what you want.

Have you ever served a huge HTML file (e.g., a file bloated with JavaScript code) and wondered how you could send it compressed, thus dramatically cutting down the download times? After all, Java applets can be compressed into a jar and benefit from faster download times. Why can’t we do the same with plain text files (HTML, JavaScript, etc.)? Plain text can often be compressed by a factor of 10.

Apache::GzipChain

can help you with this task. If a client

(browser) understands gzip encoding, this module

compresses the output and sends it downstream. The client

decompresses the data upon receiving it and renders the HTML as if it

was fetching uncompressed HTML. Furthermore, this module is used as a

filter, thanks to Apache::OutputChain, and can

therefore compress not only static files but also dynamic content

created from your handlers or scripts.

For example, to compress all HTML files on the fly, do this:

<Files *.html>

SetHandler perl-script

PerlHandler Apache::OutputChain Apache::GzipChain Apache::PassFile

</Files>Browsers are supposed to declare that they can handle compressed

input by setting the Accept-Encoding header.

Unfortunately, many browsers cannot handle it, even if they claim

that they can. Apache::GzipChain keeps a list of

user agents, and also looks at the User-Agent

header to check for browsers known to accept compressed output.

As an example, if you want to return compressed files that will in

addition pass through the Embperl module, you

would write:

<Location /test>

SetHandler perl-script

PerlHandler Apache::OutputChain Apache::GzipChain \

Apache::EmbperlChain Apache::PassFile

</Location>Watch the access_log file to see how many bytes were actually sent, and compare that with the bytes sent using a regular configuration.

Notice that the rightmost PerlHandler must be a

content producer. Here we are using

Apache::PassFile, but you can use any module that

creates output.

Alternatively, you may want to try

Apache::Compress, which is compatible with

Apache::Filter and is covered in Appendix B. To compress only outgoing static files, you

can look at the mod_gzip and mod_deflate modules for Apache.

The cool thing about these modules is that they don’t require any modification of the code. To enable or disable them, only httpd.conf has to be tweaked.

Apache Performance Notes: http://httpd.apache.org/docs/misc/perf-tuning.html.

OS-specific hints on running a high-performance web server: http://httpd.apache.org/docs/misc/perf.html.

“The Case for Persistent-Connection HTTP,” by Jeffrey C. Mogul: http://www.research.compaq.com/wrl/techreports/abstracts/95.4.html.

This paper discusses the pros and cons of persistent-connection HTTP, in particular talking about

KeepAlive.Chapter 9 (“Tuning Apache and mod_perl) in mod_perl Developer’s Cookbook, by Geoffrey Young, Paul Lindner, and Randy Kobes (Sams Publishing).

[1] Of course, you also have to take into account the shared memory usage, as described in Chapter 10.

[2] When we tried the same benchmark on different machines with a much stronger CPU and more memory, we saw different results. So we would like to stress again that the optimal configuration choices for a given application and load pattern may vary from machine to machine.

Get Practical mod_perl now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.