Preface

Odds are good that you’re already running Mac OS X (that’s “oh-ess ten,” not “oh-ess ex,” by the way) and have been for a while. In fact, if you’ve purchased new Apple hardware in the last few years, you haven’t had a choice but to jump into this new world of operating systems. If you’re like most people, there was a bit of psychic jarring when you left the familiar Mac OS 9 behind; Mac OS X is a remarkable achievement—fast, stable, and very powerful—so the transition has been most worthwhile.

On a daily basis, the major change in Mac OS X is the graphical interface, known as Aqua, which has new buttons, a new appearance, and even an entirely different multiuser architecture that was never before a core part of the Mac OS. What you might not have realized, however, is that it was the underpinnings of the operating system that changed the most in the update to Mac OS X, and that you now have a tremendously powerful OS that can run thousands of open source applications downloaded free from the Net and a command-line interface that makes even the most complex task a breeze. Tasks that Windows users wouldn’t even dream of attempting and that old Mac users would be allocating hours or even days to accomplish.

If you want to learn the key phrases, beneath Mac OS X lies an operating system called Unix (pronounced “you-nicks”), specifically UC Berkeley’s BSD Unix and the Mach kernel, a multiuser, multitasking operating system. Being multiuser means Mac OS X allows multiple users to share the same system, each with their own settings, preferences, and separate filesystems, secured from another user’s prying eyes. Being multitasking means Mac OS X can easily run many different applications at the same time, and if one of those applications crashes or hangs, the entire system doesn’t need to be rebooted like it did in the past. Instead, you just force quit the application that’s causing the “Spinning Beach Ball of Death” (you know, when the mouse pointer turns into a wildly spinning color wheel that just won’t stop rotating) and move along like nothing ever happened.

The fact that Mac OS X has Unix under the hood doesn’t matter to users who simply want to use its slick graphical interface to run their applications or manage their files. But it opens up a world of possibilities for users who want to dig a little deeper. The Unix command-line interface, which is accessible through the Terminal application (/Applications/Utilities), provides an enormous amount of power for intermediate and advanced users. What’s more, once you’ve learned to use Unix in Mac OS X, you’ll also be able to use the command line in other versions of Unix, such as FreeBSD (which is where Mac OS X derives its Unix core) or even Linux.

This book is designed to teach Macintosh users the basics of Unix. You’ll learn how to use the command line (which Unix users refer to as the shell) and the filesystem, as well as some of Unix’s most useful commands. I’ll also give you a tour of some great applications you can download off the Internet and run within X11, the Unix graphical interface that’s included with your Mac OS X system (a free, but optional install with Mac OS X, discussed in detail in Chapter 9). Unix is a complex and powerful system, so I can only scratch only the surface, but I’ll also tell you how to deepen your Unix knowledge once you’re ready for more.

Who This Book Is For

This book is for savvy Mac users who are comfortable enough in their own skin (the Finder and other GUI applications), but also want to learn more about the “Power of Unix” that Apple keeps talking about. Here, you’ll learn all the basic commands you need to get started with Unix. Instead of burying you with lots of details, I want you to be comfortable in the Unix environment as soon as possible. So I cover each command’s most useful features instead of describing all its options in detail. And let me tell you, Unix has thousands of commands with millions of options. It’s very powerful! But, fortunately, it’s just as powerful and helpful even if you just focus on a core subset and gradually learn more as you need additional power and capabilities.

Who This Book Isn’t For

If you’re seeking a book that talks about how to build Mac software applications, this isn’t your book (although it’s quite helpful for developers to have a firm grasp of Unix essentials, because you never know when you’re going to need them). If you’re a complete beginner and are occasionally stymied by where the second mouse button went, this might be a better book to put on the shelf until you’re more comfortable with your Macintosh.

Finally, if you live and breathe Unix every day, this book is probably too basic for you. I also don’t cover either Unix system administration or Mac system administration from the command line. For example, if you already know what a PID is and how to killa program, this book is probably beneath your skill level. But if you don’t know what that means, or if you’re somewhere in between, you’ve found the right book!

A Brief History of Unix

The Macintosh started out with a single-tasking operating system that allowed simple switching between applications through an application called the Finder. More recent versions of Mac OS have supported multiple applications running simultaneously, but it wasn’t until the landmark release of Mac OS X that true multitasking arrived in the Macintosh world. With Mac OS X, Macintosh applications run in separate memory areas; the Mac is a true multiuser system that also finally includes proper file-level security.

To accomplish these improvements, Mac OS X made the jump from a proprietary underlying operating environment to Unix. Mac OS X is built on top of Darwin, a version of Unix based on BSD 4.4 Lite, FreeBSD, NetBSD, and the Mach microkernel.

Unix itself was invented more than 35 years ago for scientific and professional users who wanted a very powerful and flexible OS. It has evolved since then through a remarkably circuitous path, with stops at Bell Telephone Labs, UC Berkeley, research centers in Australia and Europe, and also received some funding from the U.S. Department of Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). Because Unix was designed by experts for experts (or “geeks,” if you prefer), it can be a bit overwhelming at first. But after you get the basics (from this book!), you’ll start to appreciate some of the reasons to use Unix:

It comes with a huge number of powerful programs. You can get many others for free on the Internet. (The Fink project, available from SourceForge—http://fink.sourceforge.net—brings many open source packages to Mac OS X.) You can thus do much more at a much lower cost. Another place to explore is the cool DarwinPorts project, where a dedicated team of software developers are creating Darwin versions of many popular Unix apps (http://www.opendarwin.org/projects/darwinports).

Unix is pretty much the same, regardless of whether you’re using it on Mac OS X, FreeBSD, or Linux, or even in tiny embedded systems or a giant supercomputer. After you read this book, you’ll not only learn how to harness the “Power of Unix,” but you’ll also be ready to use many other kinds of Unix-based computers without learning new commands for each one.

Versions of Unix

There are several versions of Unix. Some past and present commercial versions include Solaris, AIX, and HP/UX. Freely available versions include Linux, NetBSD, OpenBSD, and FreeBSD. Darwin, the free Unix version underneath Mac OS X, was built by grafting an advanced version called Mach onto BSD, with a light sprinkling of Apple magic for the Aqua interface.

Although GUIs and advanced features differ among Unix systems, you should be able to use much of what you learn from this introductory handbook on any system. Don’t worry too much about what’s from what version of Unix. Just as English borrows words from French, German, Japanese, Italian, and even Hebrew, Mac OS X’s Unix borrows commands from many different versions of Unix—and you can use them all without paying attention to their origins.

From time to time, I explain features of Unix on other systems. Knowing the differences can help you if you ever want to use another type of Unix system. When I write “Unix” in this book, I mean “Unix and its versions,” unless I specifically mention a particular version.

Interfaces to Unix

Unix can be used as it was originally designed: on typewriter-like terminals, from a prompt on a command line. Most versions of Unix also work with window systems (or GUIs). These allow each user to have a single screen with multiple windows—including “terminal” windows that act like the original Unix interface.

Mac OS X includes a simple terminal application for accessing the command-line level of the system. That application is called the Terminal and is closely examined in Chapter 2.

And while you can use your Mac quite efficiently without issuing commands in the Terminal, that’s where we’ll spend all of our time in this book. Why?

Every modern Macintosh has a command-line interface. If you know how to use the command line, you’ll always be able to use the system.

If you become a more advanced Unix user, you’ll find that the command line is actually much more flexible than the graphical Mac interface. Unix programs are designed to be used together from the command line—as “building blocks”—in an almost infinite number of combinations, to do an infinite number of tasks. No windowing system I’ve seen has this tremendous power.

You can launch and close any Mac program from the command line.

Once you learn to use the command line, you can use those same techniques to write scripts. These little (or big!) programs automate jobs you’d have to do manually and repetitively with a window system (unless you understand how to program a window system, which is usually a much harder job). See Chapter 11 for a brief introduction to scripting.

In general, text-based interfaces are much easier than graphical computing environments for visually impaired users.

We aren’t saying that the command-line interface is right for every situation. For instance, using the Web—with its graphics and links—is usually easier with a GUI web browser within Mac OS X. But the command line is the fundamental way to use Unix. Understanding it will let you work on any Unix system, with or without windows. A great resource for general Mac OS X information (the GUI you’re probably used to) can be found in Mac OS X: The Missing Manual by David Pogue (Pogue Press/O’Reilly).

How This Book Is Organized

This book will help you learn Unix on your Mac fast. As a result, the chapters are organized in a form that gets you started quickly and then expands your Unix horizons, chapter by chapter, until you’re comfortable with the command line and with X11-based open source applications and able to push further into the world of Unix. Specific commands are previewed in earlier chapters, for example, and then explained in detail in later chapters (with cross references so you don’t get lost). Here’s how it’s all laid out:

- Chapter 1, Why Use Unix?

Graphical interfaces are useful, but when it’s time to become a power user, really forcing your Mac to do exactly what you want, when you want it, nothing beats the power and capability of the Unix command line. You’ll see exactly why that’s the case in this first chapter.

- Chapter 2, Using the Terminal

It’s not the sexiest application included with Mac OS X, but the Terminal, found in the /Applications/Utilitiesfolder, opens up the world of Unix on your Mac. This chapter explains how to best use it and customize it for your own requirements.

- Chapter 3, Exploring the Filesystem

Once you start using Unix, you’ll be amazed at how many more files and directories are on your Mac, information that’s hidden from the graphical interface user. This chapter takes you on a journey through your Mac’s filesystem, showing you how to list files, change directories, and explore the hidden nooks and crannies of Tiger.

- Chapter 4, File Management

Now that you can move around in your filesystem, it’s time to learn how to look into individual files; copy or move files around; and even create, delete, and rename directories. This is your first introduction to some of the most powerful Unix commands, too, including the text-based vieditor.

- Chapter 5, Finding Files and Information

If you’ve ever looked for a file with the Finder or Spotlight, you know that some types of searches are almost impossible. Looking for a file that you created exactly 30 days ago? Searching for that file with the Finder will prove to be an exercise in futility. But that’s exactly the kind of search you can do with Unix’s find, locate, and grepcommands, as well as Spotlight’s command-line utilities.

- Chapter 6, Redirecting I/O

One of the most powerful elements of the Unix command line is that you can easily combine multiple commands to create new and unique “super-commands” that perform exactly the task you seek. You’ll learn exactly how you can save a command’s output to a file, use the content of files as the input to Unix commands, and even hook multiple commands together so that the output of one is the input of the next. You’ll see that Unix is phenomenally powerful, and easy, too!

- Chapter 7, Multitasking

As mentioned earlier, Unix is a multitasking operating system that allows you to have lots of applications running at the same time. In this chapter, you’ll see how you can manage these multiple tasks, stop programs, restart them, and modify how they work, all from the Unix command line.

- Chapter 8, Taking Unix Online

Much of the foundation of the Internet was created on Unix systems, and it’s no surprise that you can access remote servers, surf the Web, and interact with remote filesystems all directly from the command line. If you’ve always wanted more power when interacting with remote sites, this chapter dramatically expands your horizons.

- Chapter 9, Of Windows and X11

The graphical interface in Mac OS X is the best in the industry. Elegant and intuitive, it’s a pleasure to use. But it turns out that there’s another, Unix-based graphical interface lurking in your Mac system, called the X Window System, or X11 for short. This chapter shows you how to install X11 from Tiger’s install DVD and gives you a quick tour of some of the very best X11 applications available for free on the Internet.

- Chapter 10, Open Source Software Via Fink

We Mac OS X users are spoiled with the Software Update utility and commercial application installers. However, the world of X11 and open source applications is more anarchic, which is why it’s a blessing that a team of talented Mac programmers have created a software distribution and installation tool called Fink. Learning about Fink is a smart move for any Mac Unix user who wants to experience the full range of free software in the market.

- Chapter 11, Where to Go from Here

With all its commands, command-line combinations, and the addition of thousands of open source utilities free for the downloading, you can spend years learning how to take best advantage of the Unix environment. In this final chapter, I offer you some directions for your further travels, including recommendations for favorite books, web sites, and similar.

Conventions Used in This Book

The following typographical conventions are used in this book:

- Plain text

Indicates menu titles, menu options, menu buttons, and keyboard accelerators (such as Alt and Control).

- Italic

Indicates new terms; example URLs; email addresses; filenames; file extensions; pathnames; directories; and Unix commands, utilities, and options.

-

Constant width Indicates commands and options in code samples, variables, attributes, values, the contents of files, or the output from commands.

-

Constant width bold Shows commands or other text that should be typed literally by the user.

-

Constant width italic Shows text that should be replaced with user-supplied values.

- Menus/navigation

Menus and their options are referred to in the text as File → Open, Edit → Copy, etc. Arrows are also used to signify a navigation path when using window options; for example, System Preferences → Screen Effects → Activation means you would launch System Preferences, click on the icon for the Screen Effects preferences panel, and select the Activation pane within that panel.

- Pathnames

Pathnames are used to show the location of a file or application in the filesystem. Directories (or folders for Mac and Windows users) are separated by forward slashes. For example, if you see something like “launch the Terminal application (/Applications/Utilities)” in the text, that means the Terminal application can be found in the Utilities subfolder of the Applications folder.

- ↲

A carriage return (↲) at the end of a line of code is used to denote an unnatural line break; that is, you should not enter these as two lines of code, but as one continuous line. Multiple lines are used in these cases due to printing constraints.

- Menu symbols

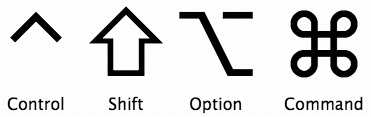

When looking at the menus for any application, you will see some symbols associated with keyboard shortcuts for a particular command. For example, to open a document in Microsoft Word, you could go to the File menu and select Open (File → Open), or you could issue the keyboard shortcut, ⌘-O.

Figure P-1 shows the symbols used in the various menus to denote a keyboard shortcut.

Rarely will you see the Control symbol used as a menu command option; it’s more often used in association with mouse clicks to emulate a right click on a two-button mouse or for working with the bash shell.

$,#The dollar sign (

$) is used in some examples to show the user prompt for the bash shell; the hash mark (#) is the prompt for the rootuser.

Using Code Examples

This book is here to help you get your job done. In general, you may use the code in this book in your programs and documentation. You do not need to contact us for permission unless you’re reproducing a significant portion of the code. For example, writing a program that uses several chunks of code from this book does not require permission. Selling or distributing a CD-ROM of examples from O’Reilly books does require permission. Answering a question by citing this book and quoting example code does not require permission. Incorporating a significant amount of example code from this book into your product’s documentation does require permission.

We appreciate, but do not require, attribution. An attribution usually includes the title, author, publisher, and ISBN. For example: "Learning Unix for Mac OS X Tiger, Fourth Edition, by Dave Taylor. Copyright 2005 O’Reilly Media, Inc., 0-596-00915-1.”

If you feel your use of code examples falls outside fair use or the permission given above, feel free to contact us at permissions@oreilly.com.

Safari® Enabled

When you see a Safari® Enabled icon on the cover of your favorite technology book, that means the book is available online through the O’Reilly Network Safari Bookshelf.

Safari offers a solution that’s better than e-Books: it’s a virtual library that lets you easily search thousands of top tech books, cut and paste code samples, download chapters, and find quick answers when you need the most accurate, current information. Try it for free at http://safari.oreilly.com.

Comments and Questions

Please address comments and questions concerning this book to the publisher:

| O’Reilly Media, Inc. |

| 1005 Gravenstein Highway North |

| Sebastopol, CA 95472 |

| (800) 998-9938 (in the United States or Canada) |

| (707) 829-0515 (international or local) |

| (707) 829-0104 (fax) |

We have a web page for this book, where we list errata, examples, and any additional information. You can access this page at:

| http://www.oreilly.com/catalog/lunixtiger |

To comment or ask technical questions about this book, send email to:

| bookquestions@oreilly.com |

For more information about our books, conferences, Resource Centers, and the O’Reilly Network, see our web site at:

| http://www.oreilly.com/ |

You can also contact the author on his own web site:

| http://www.AskDaveTaylor.com/ |

The Evolution of This Book

This book is loosely based on the popular O’Reilly title Learning the Unix Operating System, by Jerry Peek, Grace Todino, and John Strang (currently in its fifth edition). There are lots of differences in this book to meet the needs of Mac OS X users, but the fundamental layout and explanations are the same. The Tiger edition is the fourth Mac OS X custom edition of this title. As Mac OS X keeps getting better, so does this little book.

Acknowledgments

I’d like to acknowledge the work of Chuck Toporek, my editor at O’Reilly. I would also like to express my gratitude to Brian Jepson, my co-author on the previous editions of this book. Brian, I’m sorry your cat’s no longer featured in the GIMP section! Thanks also to Christian Crumlish for his back-room assistance, and to Tim O’Reilly for the opportunity to help revise the popular Learning the Unix Operating System book for the exciting Mac OS X world. Oh, and a big thumbs up to Linda, Ashley, Gareth, and Kiana for letting me type, type, and type some more, ultimately getting this book out the door in a remarkably speedy manner.

Get Learning Unix for Mac OS X Tiger now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.