If you have a typical pocket camera, skip this section. It's reserved for the owners of SLRs and a very few advanced, more expensive smaller cameras.

It's about the RAW file format. Understanding it requires some background.

See, most cameras work like this: When you squeeze the shutter button, the camera studies the data picked up by its sensors. Based on this analysis, the software makes decisions about how much to sharpen the photo, which white balance setting to use, how to set the exposure levels, how saturated the colors should be, how high the contrast ought to be, and so on. The camera crunches the raw data from the sensor, locks in all of these settings, and spits out, onto your memory card, a processed, finished JPEG graphics file.

For millions of peopleâincluding plenty of professionalsâthe resulting picture quality is just fine, even terrific.

But there's another crowd, consisting of professionals and advanced amateurs, who can't stand the thought of all that in-camera processing. They'd much rather make all of those creative decisions themselves. They'd prefer that the camera not process the original image data at all, and instead deliver every iota of original picture information onto the memory card. That way, later, these pros can process the file by hand once it's been safely transferred to the computer, using a program like Photoshop, Photoshop Elements, Picasa, iPhoto, Lightroom, or Aperture.

That's the idea behind the RAW file format, an option in every SLR and a few pricier compacts.

Note

RAW stands for nothing in particular, and it's usually written in all capital letters like that just to denote how important serious photographers think it is. (In fact, it's not even a standard file format. Every camera company has its own RAW file format. The Nikon format is called .NEF; the Canon format is .CRW; and so on. Now you know why owning Adobe Photoshop entails downloading frequent updates; Adobe is constantly releasing new RAW file interpreters to keep up with the new camera models on the market.)

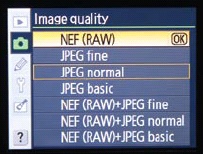

You choose what you want the camera to captureâRAW files, JPEG files, or both at onceâusing its menus.

The beauty of RAW files is that once you open them up on the Mac or PC, you can perform astounding acts of editing on them. For example, you can change the white balance or the exposure of the scene after the fact. And you don't lose a single speck of image quality along the way.

Note, however, that there are two huge downsides to shooting in the RAW format (or "shooting RAW," as shutterbugs say).

First, a RAW image isn't compressed to save space; it's a complete record of all the data passed along by the camera's sensors. As a result, it's huge. It fills up your memory card much faster, fills up your hard drive much faster, and takes much longer to transfer from the former to the latter. For example, on a 12-megapixel camera, a JPEG photo is around 3 MB, but the same picture is over 10 MB when saved as a RAW file. Most cameras take longer to store RAW photos on the card, too, which can really put a damper on burst mode shots.

Second, RAW editing is a serious time drain. You wind up spending several minutes, or maybe many minutes, on each photo, tweaking it to perfection as your life ticks away. It's worth it for a professional wedding photographer or someone on assignment for a magazine.

But in the meantime, remember that you can edit regular JPEG files in many of the same ways (just not as radically). Depending on the kind of shooting you do, the reasons you shoot, and the importance of your photos to the outside world, opting for the RAW format may not be worth it.

Get David Pogue's Digital Photography: The Missing Manual now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.