Few CACs make their revenues and expenses transparent. The only CAC we could find that published any budget numbers was Washington DC’s Apps for Democracy, which reported an expense of $50,000. But that number reflects a one-time payment to iStrategyLabs to run the competition. Each NYCBig Apps is about $100,000 all-inclusive, but a breakout by task isn’t available.

We’re going sidestep this lack of precedent in two ways: by walking you through the priciest components of a CAC (cash prizes, web platform, administrative support, technical support and competition length); and by publishing for the first time ever what the Metro Chicago Information Center (MCIC) spent on running the Apps for Metro Chicago competition (A4MC) in 2011. Keeping these costs in mind will help you design a competition that fits your budget. We’ll also explore the ways that partners and sponsors can reduce your costs.

Most CACs require partnerships, and for the discussion below to make sense, we should describe a typical competition’s partners—there are five kinds. First, if the City or other government agency isn’t running the competition itself, there’s likely to be a managing partner—for us, that was MCIC. The city and other government suppliers of data are data partners. Then there are funding partners who put up prize money and fund administration of the competition. Sponsorship partners donate time, space or money for events, give in-kind contributions such as testing devices, or in-kind prizes such as cloud services for winners. An important subset of sponsorship partners are apps sponsors. These are organizations that are interested in supporting the development of a particular kind of app. For example, in A4MC the Delta Institute sponsored the development of a “green app” by putting up a bit of prize money and sponsoring a hack day.

Governments collect data in a variety of ways, and sadly the data sets are stored in a variety of ways too. Since developers need clean, structured data to build apps (more on this in the next chapter), you may have to undertake a data clean-up as the first step in the competition. If resources for data development need to be taken into account, that will take a bite out of the competition budget. Depending on your level of readiness, these costs can range from the tens of thousands to the hundreds of thousands. Apps for Metro Chicago benefited from already-structured data sitting on RESTful web servers that had been developed over the course of 18 months before the CAC was announced. While the city government declined to provide information about the cost of preparing the initial 70 data sets that we used to start the competition, we estimate the cost to the city at roughly $100,000.

Over the past three years, award amounts have grown by leaps and bounds. The biggest prize pool we found clocked in at $100,000 for 2011’s Apps for Communities, which was run by the Knight Foundation and the Federal Communications Commission. Apps for Metro Chicago’s final bill for cash prizes was about $65,000, including the original amount set aside by the City of Chicago, as well as add-on prizes for apps sponsored by specific organizations.

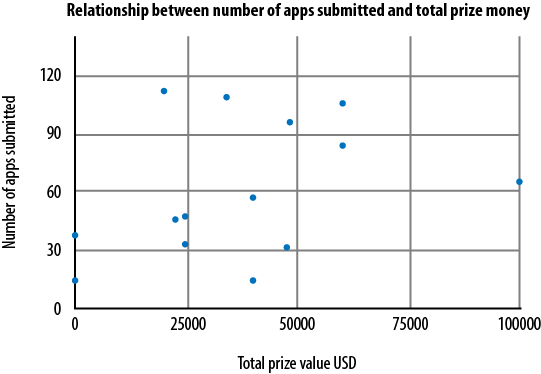

But we have good news for organizers without that kind of money: a review of 15 North American CACs shows no relationship between the number of entries and the size of the prize money pool (Figure 4-1).

Notice that five CACs offering less prize money attracted more submissions than Apps for Communities; and the EPA’s Apps for the Environment collected 38 entries despite offering no cash at all.

We still recommend offering cash prizes, but the jury is out on whether or not it’s the best to splurge. Although they remain an important incentive, it looks like there are diminishing returns at some point. However, Tom Lee at Sunlight Labs maintains that prizes were “vital to Sunlight’s Civic Apps Competitions.”[10]

All competitions require a web-based platform to share information about the competition, allow developers to submit their apps, and possibly run a public voting process. Competition organizers have two choices: build a one-off competition website, or work with an established vendor like ChallengePost, Skild, or NetSquared. These vendors offer anything from simply hosting a competition website to designing the entire effort, recruiting applicants, drafting rules, and distributing prizes.

Given the lack of transparency about competition budgets to date, it is difficult to conduct a thorough cost-benefit analysis of hiring a vendor or building a one-off website. Nevertheless, there are a number of factors that every organizer should consider:

Is there anyone in-house who can build a site with all the features you need?

How long would it take your staff to build and maintain that site?

How much do you have to spend?

Are you planning to host future competitions, or is this competition a one-time event?

It is very easy to underestimate the cost of building a one-off site capable of hosting comments, managing app submissions, and handling public voting. For example, A4MC hired a contractor to build a standalone competition site using free open source software and the bill still exceeded $60,000. If you don’t have the internal expertise to build a site, you should strongly consider hiring a vendor. Table 4-1 is meant to be a handy guide to help you decide whether you should build a one-off or not.

Keep in mind that, whether you build it in-house or out, the cost of additional features rarely makes them worth it. A4MC included a “conversation” area where we encouraged developers and community groups to do matchmaking, but in reality that’s a function that we really needed to do in person (see more below). A developer conversation area was similarly little-used. Stick to the basics—the platform really only needs to explain the rules and regulations of the contest, host submitted apps, and handle public voting.

Table 4-1. Building a one-off vs. hiring a vendor

| Pros | Cons | Recommended for | |

|---|---|---|---|

Custom platform |

|

|

|

Vendor platform |

|

|

|

Running even a simple CAC requires a lot of behind-the-scenes work and it’s important to budget enough staff to manage it. Because staffing varies so widely across offices, we’re breaking out the administrative tasks necessary for running a CAC, as well as providing a list of roles. The list may feel overwhelming, but as they say the devil’s in the details. In our experience the cost is in the details, too.

The role of the project director is to conceptualize the competition, get the project started, make the initial connections among partners and sponsors, set up the “rules of the road,” and direct high-level traffic. The project director might be the same person as the project manager (described next), but if that’s the case, realize that this person will need to juggle air-traffic control, along with day-to-day ground support and maintenance throughout the competition. MCIC spent $35,000 on such high-level tasks which include:

Setting the frame

Generating internal support

Designing competition structure

Establishing competition goals and design

Designing rules, timing and prize categories

Creating budget(s) and partnership agreements

Identifying key players

Recruiting partners and/or sponsors

Finding prize money and sponsorships

Identifying and recruit judges

Leading the partnership

Resolving conflicts

Taking calls from organizational and community leaders

Making major decisions on strategy and direction

The project manager is in control of day-to-day operations. The list of tasks below represents a potentially incredible amount of work and attention to detail, depending on the complexity of the competition design and the number of partners. MCIC spent $75,000 on project management for A4MC for the following tasks:

Develop the project timeline, meeting schedule, and keep everyone on task

Develop and spearhead outreach plans to community organizations and software developers

Develop the rules and regulations, undertake a legal review

Coordinate external partners

Field calls and develop relationships with partners and sponsors

Plan for coordinated marketing and outreach and media strategy

Vendors and events

Find venues and participants for events

Organize hackathons

Organize prize award ceremonies

Oversee judging

Develop judging rubric and ensure compliance

Cajole and track judges and oversee judging process

Obtain platforms for judges to enable them to evaluate the apps

Oversee vote tallying and identify potential issues to check for cheaters

Coordinate internal communications, event, legal and competition website staff

One of the main themes of the Apps for Metro Chicago competition was to emphasize community outreach in a way perhaps not done before. Our intention was to generate apps that addressed important issues by Chicago area residents; because community organizations deal with these issues, they are best situated to understand the dynamic needs of their communities. Ideally this outreach would result in apps which are just not technologically innovative, but helpful for the day to day lives of Chicago residents—and that because the apps generated met community needs, they would be more likely to have longevity.

We set up a Google Group to facilitate matchmaking. We’d hoped that community organizations would go to the Google Group themselves, seek out a partner, and only need our help for data questions and getting started. But this was a high expectation. Instead, we took on the task of publishing their ideas to the Google Group and directing any responses back to them. We then called them, scheduled a brainstorming session, gathered ideas, and matched them with a developer. Negotiating trust, overcoming the technical language barrier and facilitating the relationship was fairly complex. This outreach and match-making contributed about $20,000 to the costs of project management.

Unless done by the project manager, the role of a communications specialist is to coordinate media and outreach. The more partners and the more rounds of competition, the larger the budget. The communications director’s task is also made more difficult when trying to reach multiple audiences and participants: community groups, developers, artist communities, etc. The A4MC budget was about $75,000 for tasks such as:

Developing press and social media strategy

Creating content for social media channels

Organizing events

The role of technical support is to manage internal technical issues around the competition and respond to developer requests and questions. For A4MC, we included technical assistance on the metadata, and review of the use of the data in the app itself. We spent $55,000 on technical support:

Build and/or manage the competition website

Answer developer questions about data

Escalate information about bugs and data errors to the data partners

Screen app submissions for functionality and adherence to competition rules

Support judges during the app judging process

Monitor public voting for cheating

The managing partner should have a lawyer available to review the rules of the competition and protect the partners from liability.

Ensure the competition rules are in compliance with the law

Protect the organizers from liability

Protect the partners from liability

Not all competitions are complicated enough to require all these tasks, but even the simplest competition takes serious time and effort to pull off. Be realistic in your assessment of the working hours needed to accomplish administrative tasks and design your competition accordingly. A shorter, simpler competition that runs well is far preferable to a long, complex competition that annoys all the organizers and participants. Given the number of partners and the complexity of relationships, legal review cost A4MC $25,000.

The legal version of our rules and regulations are available at www.urbanrubrics.com.

There are two kinds of of technical support you may decide to include in your CAC: managing the competition website, and answering developers’ questions about the data. We touched on the need to have someone manage the competition website above, so here we will focus on what we believe was one of the distinctive characteristics of A4MC: cleaning competition data and answering questions about it.

One of the great truths of life is that developers will find errors in the course of working with data, no matter how stringently it’s cleaned beforehand. They will attempt to report them to you and will be annoyed if they are ignored.

A simple way to manage questions and complaints is to set up a ticket-based support system like Zendesk or osTicket. These systems collect questions and error reports from developers and direct them to support staff. Once the questions are answered they can be posted on the competition site for other developers to access.

Most competitions do not provide competing developers with systematic technical support, but it is a good way to improve the quality of both the raw data and the competition apps.

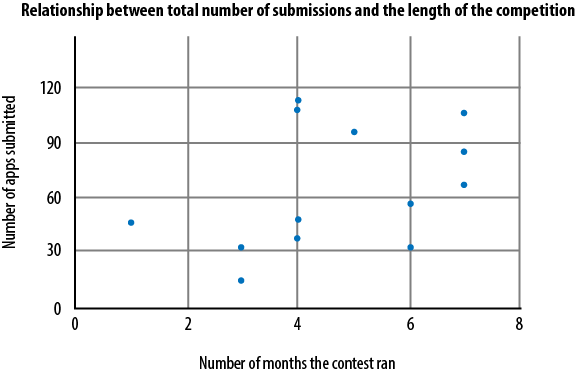

The CACs we surveyed ranged from 1 to 7 months in length, but, as Figure 4-2 shows, adding extra time after the 4 month mark doesn’t have much effect on the quantity of apps submitted.

Of course, we don’t know if the length of the competition has an effect on the quality of the apps. We’re inclined to think that quality is influenced more by good communications, networking and hackathons than the number of months the competition runs. So if you have to trim the budget somewhere, we recommend shortening the competition.

Other costs that you may need to budget for include:

- Support for the judges

Judges need smartphones upon which to judge the apps, will have questions for the technical staff, etc. Be sure to ask yourself “Where will these smartphones come from?”

- The time/cost of finding venues for and coordinating events

This takes much longer than one might think. The cost for this to A4MC was about $20,000.

- Managing post-contest complaints

A4MC fielded complaints from developers who didn’t win, some of whom challenged the legality of particular apps.

After that list of competition expenses you’re probably just about ready to hurl this book across the room. Before you do, think about whether or not you can recruit partners or sponsors to help defray the costs. Many of the apps competition we reviewed had partners and sponsors. Canada’s Apps 4 Climate teamed up with Microsoft, SAP, Telus, Netscribe, Analytic Design Group, eaves.ca, Harbour Air Seaplanes, and the Vancouver Aquarium. And that wasn’t even the competition with the most partners and sponsors—that honor goes to Portland’s Civic Apps, which clocked in at a whopping 16 partners and sponsors.

The downside of recruiting partners is that you lose some control over the structure of the competition. For example, A4MC was funded largely by the MacArthur Foundation and the Chicago Community Trust, two foundations that support non-profits and charitable causes. As a result, the competing developers were required to make their apps free to the public for a year instead of being able to bring them to market. We found that this put off a number of would-be competitors.

Usually the upsides to partnering more than make up for the drawbacks—and not just for the funding. Apps for Metro Chicago was able to leverage the CCT and MacArthur networks to engage non-profits and other civic institutions in the competition.

An important lesson we learned in terms of administration is that the administrative resources you will need to devote to these tasks tend to increase exponentially as more partners come on board. Having more partners is a fabulous thing—whether they are app sponsors, data providers (A4MC had data from the state, the county, the city and the local regional planning agency), or other backers. A variety and large number of partners can be a boon to the competition terms of the apps that can be built and the buzz generated. However, each partner adds another dimension to the social media strategy, coordination efforts, input-to-be-obtained-from, etc. We took at least one late-night call from a partner unhappy about the placement of their logo on the competition website. Partners are great, but they’re a double-edged sword.

Also, not all partners are equal in their ability to take on their required tasks (such as developing marketing and outreach for their sponsored app). When entering into partnerships, be sure to structure the relationship so that it truly fits the task at hand and the available resources. What we learned is that expectations needed to be made explicit. Assumptions about the ability to piggyback on existing capacity can lead to a fraught relationship and unrealistic expectations. Organizations that want to sponsor an app, for example, might not have the ability to do a media roll-out and might need help from the managing partner to do that.

The largest two items that contributed to administrative costs are apt to be the number of competition rounds and the number of partners. This presents a conundrum: more rounds create more excitement and engagement and potential for good apps, but they come at a price.

More partners also means more data and more possibilities for cross-fertilization, but again, this creates a greater workload for the managing partner.

A budget is necessary, but the really critical resource for a terrific competition is a good data selection. In the next chapter we walk you through everything you need to know to assess your data resources.

Get Civic Apps Competition Handbook now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.